Sam Stiefel – The Producer and Conman Who Inspired James Ellroy

Armand Ellroy, James Ellroy’s father, was an accountant and Hollywood fixer. His most notable Hollywood connection was Rita Hayworth, whom he met in Tijuana in the 1930s and served as her business manager from 1948-52. But what about his other Hollywood contacts? Two names make fleeting but intriguing appearances in Ellroy’s memoirs when he discusses his father’s movie biz friends — former child star Mickey Rooney and ‘schlock producer’ Sam Stiefel.

Alas, precious little is known about Armand Ellroy’s friendship with either Rooney or Stiefel, whereas Hayworth biographies provide some useful information on Ellroy’s relationship with the movie star he worked for (and claimed to have bedded). However, there is an abundance of material on Rooney and Stiefel’s professional and personal relationship with each other. The two men enjoyed a friendship and business relationship that began with ‘can-do’ American optimism and descended into one of the most bitter Hollywood feuds of the 1940s, as Rooney gradually realised he was being extorted by a conman, charlatan and alleged Jewish Mafia figure. Once he had extricated himself from Stiefel’s influence in the early 1950s, one can imagine that Rooney’s friendship with Ellroy must have also cooled as he didn’t want to be around any of Stiefel’s old friends. James Ellroy described Stiefel as a ‘schlock producer’, and this is a little unfair. Stiefel was both bigger than ‘schlock’ in his achievements, but sometimes smaller than it in his moral actions. He was, in every respect, an unceasingly complex man.

If Sam Stiefel had never gone to Hollywood, then the chances are that today he would be remembered as a liberal, perhaps even a visionary, reformer. Samuel H. Stiefel was born into an entrepreneurial Jewish family in Norma, New Jersey in 1897. The Stiefel family, which traced its roots back to Pokatilovo in the Ukraine, built and owned several theatres on the East Coast. Sam, who eventually took over the family business, opened the Pearl Theatre in Philadelphia in 1923 and shortly thereafter purchased the Howard Theatre in Washington DC. These venues were part of the ‘Chitlin Circuit’, which catered to largely African-American audiences and featured Black performers who, due to segregation, were blocked from appearing in all-white theatres. Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington are two performers who became famous on the Chitlin Circuit.

Mickey Rooney was on a promotional tour for the film Girl Crazy in 1943/4 when he first met Sam Stiefel at a Pittsburgh theatre. Stiefel, never lacking in confidence, asked the stage manager to pass a message to Rooney requesting a meeting, and the diminutive former child star agreed. Stiefel wined and dined Rooney and his publicist Les Peterson, and by the time Rooney was on his way back to Hollywood, he had hired Stiefel to be his business manager. Rooney was clearly naive to hire Stiefel on impulse, and there were already signs that he had misjudged his character. Peterson described Stiefel as ‘a short, squarely built man who wore suits with wide lapels and flashy silk ties and looked about as trustworthy as a pit boss in Las Vegas.’ Attorney Murray Lertzman’s assessment of Stiefel wasn’t much better: ‘He had this rough, gravelly voice […] He carried a wad of bills that would have choked a horse. He was very flashy and quite persuasive.’ Stiefel was itching to make it in Hollywood, and was seething with jealously that his former business partner Eddie Sherman had broken into the business before him after being hired as Abbott and Costello’s business manager.

In Hollywood, Stiefel continued to earn Rooney’s trust. He began extracting Rooney from his contract at MGM (where he had long felt cheated) and persuaded him to put his earnings into a company he had set up – Rooney Inc. Rooney was also a heavy gambler and Stiefel, who owned several racehorses, was happy to cover his losses. He even promised to loan Rooney’s mother cash, if and when she needed it, while the star was away.

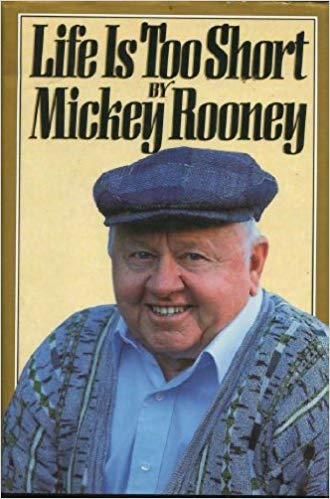

In his memoir, Life is too Short, Rooney describes how the night before he was due to leave for his army induction (he served in Special Services during World War II) his by-then ex-wife Ava Gardner seduced him wearing ‘a red nightgown and red peignoir’. The next morning, ‘I couldn’t believe what a lucky guy I was. While I was off fighting for my country, Sam Stiefel would take care of my finances and Ava would be waiting.’

In his memoir, Life is too Short, Rooney describes how the night before he was due to leave for his army induction (he served in Special Services during World War II) his by-then ex-wife Ava Gardner seduced him wearing ‘a red nightgown and red peignoir’. The next morning, ‘I couldn’t believe what a lucky guy I was. While I was off fighting for my country, Sam Stiefel would take care of my finances and Ava would be waiting.’

To be thinking about Sam Stiefel so soon after a night of passion with Ava Gardner might seem odd. However, it reveals the complete trust Rooney placed in Stiefel at this time. Armand Ellroy told his son that Rooney ‘would fuck a woodpile on the off chance that a snake might be inside.’ Armand claimed inside knowledge of the movie stars sex lives, something he may have got from Rooney whose memoir reads like a sex addict’s confessional. At a Beverly Hills party, Rooney describes stumbling into a bedroom to find Tallulah Bankhead, ‘her head between the limbs of a beautiful young blonde’. Unfamiliar with lesbianism and embarrassed, a shocked Rooney made some frantic apologies but ‘Tallulah never missed a bite, never looked up.’ Rooney’s bawdy humour occasionally seeped through the cracks of his wholesome onscreen image – did he really slip the word dildo into the aptly titled Girl Crazy?

Although he had been reluctant to join the army, Mickey Rooney had a good war. He was awarded a Bronze Star, a good conduct medal and a World War II victory medal. However, the minute he returned to American shores at New York Harbour, he sensed something was wrong. None of his family were there to greet him — only Sam Stiefel. Stiefel wanted to party with Rooney and see some shows, but Rooney insisted (according to his memoir) that he just wanted to be with his family. Back on the West Coast, Stiefel met Rooney at the Hollywood Park Racetrack. Stiefel was by now enjoying the luxurious life of a Hollywood mogul, living with his family at a showcase home in Bel Air. While puffing away on a huge cigar, Stiefel informed Rooney that he expected full repayment for all of the gambling debts he had covered. In addition, Rooney’s mother had racked up a debt with Stiefel of $159,000 which he expected the actor to repay. Stiefel had also, seemingly without permission, invested Rooney’s earnings in a racing stable which was losing money. In desperation, Rooney agreed to forgo fifty per cent of his earnings to Stiefel until his debts were cleared. ‘Having survived the Nazis, I thought I’d have an easier time when I got back to Hollywood. I was mistaken’ Rooney lamented.

This ruinous situation was affecting Rooney’s mood at MGM. Colleagues began to complain about his behaviour and, in a moment of petulance, Rooney gave Stiefel permission to sever all contact with the studio. He later described this move as:

One of the dumbest things I ever did. I had to forgo my $5,000-a-week salary and my pension […] And I had to pay Metro $500,000 besides, which I was to work off at a rate of $100,000 a picture (and keep only $25,000 for myself)). In other words, Stiefel negotiated me down to $25,000 a picture […] Now, I had to do five pictures for $25,000 apiece, minus 50 percent to Sam Stiefel and minus Uncle Sam’s share. That would bring my take down to less than $10,000 a picture – not even enough to pay my upcoming alimony and child support.

One wonders, given his role as an accountant, whether Armand Ellroy ever intuited just how badly Stiefel was scamming Rooney. There is one small clue to suggest that he may have done. Johnny Hyde was Vice-President at the William Morris Agency. He agreed to take on Rooney as a client– as a favour in return for Rooney introducing him to Marilyn Monroe– and extricate him from his business relationship with Stiefel. Hyde was also Rita Hayworth’s agent and was, alongside Armand Ellroy, one of the few Hollywood guests at her 1949 wedding to Aly Khan which Ellroy helped plan. It’s certainly possible that either Rooney or Hyde confided to Ellroy what was happening with Stiefel. Aside from their womanising, Ellroy and Rooney did have one macabre thing in common. They were both married to women who were murdered. Jean Ellroy was murdered in 1958. Rooney’s fifth wife Barbara Ann Thomason was murdered by her lover Milos Milos in 1966. Milos’s widow, Cynthia Bouron, was herself murdered in 1973.

Rooney eventually confronted Stiefel, accusing him of extortion to the tune of ‘six million, four hundred thousand, six hundred and thirteen dollars. And twelve cents’. Stiefel’s other big catch in Hollywood was Peter Lorre. He formed the company Lorre Inc and pulled off the exact same con, ‘grossly mismanaging his (Lorre’s) business affairs and leaving him in financial ruin.’ Lorre had many of the same vices as Rooney that made him a perfect target for Stiefel. Lorre was too trusting, struggled to control his spending and was battling a morphine addiction. If it is true that Stiefel was a member of the Jewish Mafia, as Murray Lertzman claimed, then he may have been passing some of this extortion money on to his superiors in the LA Underworld. Stiefel did like to flaunt his criminal connections. His friends included mobsters Bugsy Siegel and Mickey Cohen, and he was a silent partner in the latter’s clothing store – Michael’s Haberdashery. According to Stiefel’s granddaughter Adrienne Callander, Stiefel once received a call from Al Capone in prison. Scarface wanted his help in fixing the prison stage. Stiefel had made the connection with Capone after he produced a show for inmates at Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary where Capone was imprisoned on a gun charge.

Although his business relationship with Stiefel was coming to an end, Rooney couldn’t walk away just yet. He was contractually obligated to star in and co-finance three films for the still aspiring producer. First came the run of the mill sporting drama The Big Wheel (1949). The following year came the more impressive Quicksand.

In Quicksand, Rooney plays Dan Brady, a garage mechanic with an eye for a beautiful woman. Barbara Bates plays his ex-girlfriend Helen. Helen still loves him. She’s nice, she’s pretty, she’d be good for him. In a diner one night Dan meets Vera (Jeanne Cagney). She’s blonde, she’s bad, she oozes sex appeal and lusts after a $2,000 mink coat. Dan spurns Helen’s overtures and goes chasing after the femme fatale Vera. This is all going to go very wrong for Dan. Dan steals $20 from the garage till to go on a date with Vera. He buys a $100 wristwatch on instalment payments, which he then pawns for $30 to cover the missing money in the till. Then he is threatened with grand larceny for violating the instalment plan and selling a watch he doesn’t legally own. He has to buy the watch outright in 24 hours or face prison. Now he gets really desperate and mugs a sloshed bar patron, which leads to him being extorted for $3,000 by the crooked owner of the garage where he works. Vera and Dan decide to cover this debt by robbing a penny arcade run by her seedy ex-partner played by Peter Lorre (who only took on the role as he was still in hock to Stiefel). They pull off the robbery, but Vera spends her half on her beloved mink leaving Dan still owing his boss. Then things take a violent turn for the worse.

Dan’s in the quicksand. Each bad decision he makes pulls him deeper into debt and trouble with the law. Quicksand’s narrative of spiraling debt clearly evokes Rooney and Lorre’s predicament with Stiefel. Rooney disliked the film intensely. He poured his money into the production and made a loss on it as ‘Stiefel commandeered whatever cash there was.’ However, Rooney does give one of the most mature and acclaimed performances of his career. He understood the weakness for sex and bad business decisions which drove Dan Brady.

Rooney and Stiefel never collaborated on the planned third film as Stiefel didn’t like the script. And here’s the final irony, as if they had gone ahead and made Francis (1950) together as planned then Rooney and Stiefel would have raked in millions. In the event, Donald O’Connor played the leading part. It was a huge hit for Universal, spawning the Francis the Talking Mule franchise which featured six more films and inspired the TV show Mister Ed. By contrast, the two films Stiefel produced are now in the public domain, which is usually a sign of lax business practices. Both are now free to view on the internet.

Although he must have felt like a horse’s ass for passing on Francis, Sam Stiefel could be proud that he made a good film noir in Quicksand. James Ellroy dismissed Stiefel as a purveyor of schlock, which is not how I would categorise Quicksand.

That said, Ellroy does display a nostalgia for grade-Z, schlock films in his writing. There is the filming of Daddy-O in Dick Contino’s Blues, the ill-conceived comeback vehicle for the titular accordionist. Also, there is the fictional ‘Attack of the Atomic Vampire’ in White Jazz. This stinker of a horror movie is produced by Mickey Cohen in a desperate attempt to revive his standing in LA after his release from prison.

Stiefel’s links to Mickey Cohen suggests another possible influence the producer had on Ellroy’s writing. Ellroy always seemed more interested in and fond of wannabe celebrity gangster Cohen than he was in the Mafiosi of the Underworld USA trilogy – Sam Giancana, Carlos Marcello, Santo Trafficante Junior. Even though these gangsters were far more powerful than Cohen, the reader never really gets to know them as much as the vain, prickly but ultimately quite likable Jewish hoodlum. Giancana is unsympathetic as he is a lifelong gangster and leader of the Chicago Outfit, which was founded in 1910 and still operates today. By contrast, the Jewish Mafia had disappeared within a generation. As gangsters, Cohen and Stiefel really just wanted to be good immigrants and live the American Dream. They may have had a hand in the rackets, but their ambition was to reinvest their ill-gotten gains and ‘make it’ in legitimate business. Like Bugsy Siegel’s dream of building the Flamingo Hotel in the Nevada Desert, Stiefel genuinely wanted to be a great film producer. Although the fate of the Kennedy’s, as fictionalised by Ellroy in American Tabloid and The Cold Six Thousand, suggests children cannot escape paying for the sins of the father.

Quicksand may not be a masterpiece, but it is Stiefel’s enduring legacy from his time in Hollywood. Stiefel left the movie business for good in the early 1950s, leaving behind a trail of vendettas and ending one of Armand Ellroy’s last connections to the movie world (he was fired by Rita Hayworth in 1952). Stiefel returned to the theatre business in Philadelphia, promoting black musicians at a time when Soul music was beginning to emerge. When he died in 1958, Stiefel’s obituary in Time magazine described him as the ‘Father of Negro Show Business’. The Stiefel family papers are held at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. In the theatre world, Steifel could claim to have made a positive and lasting change.

Stiefel’s time in Hollywood led to a darker, more enigmatic legacy. James Ellroy could have been writing an alternative obituary for Stiefel with the words – It’s time to embrace bad men and the price they paid to secretly define their time.

Here’s to them.

Trackbacks