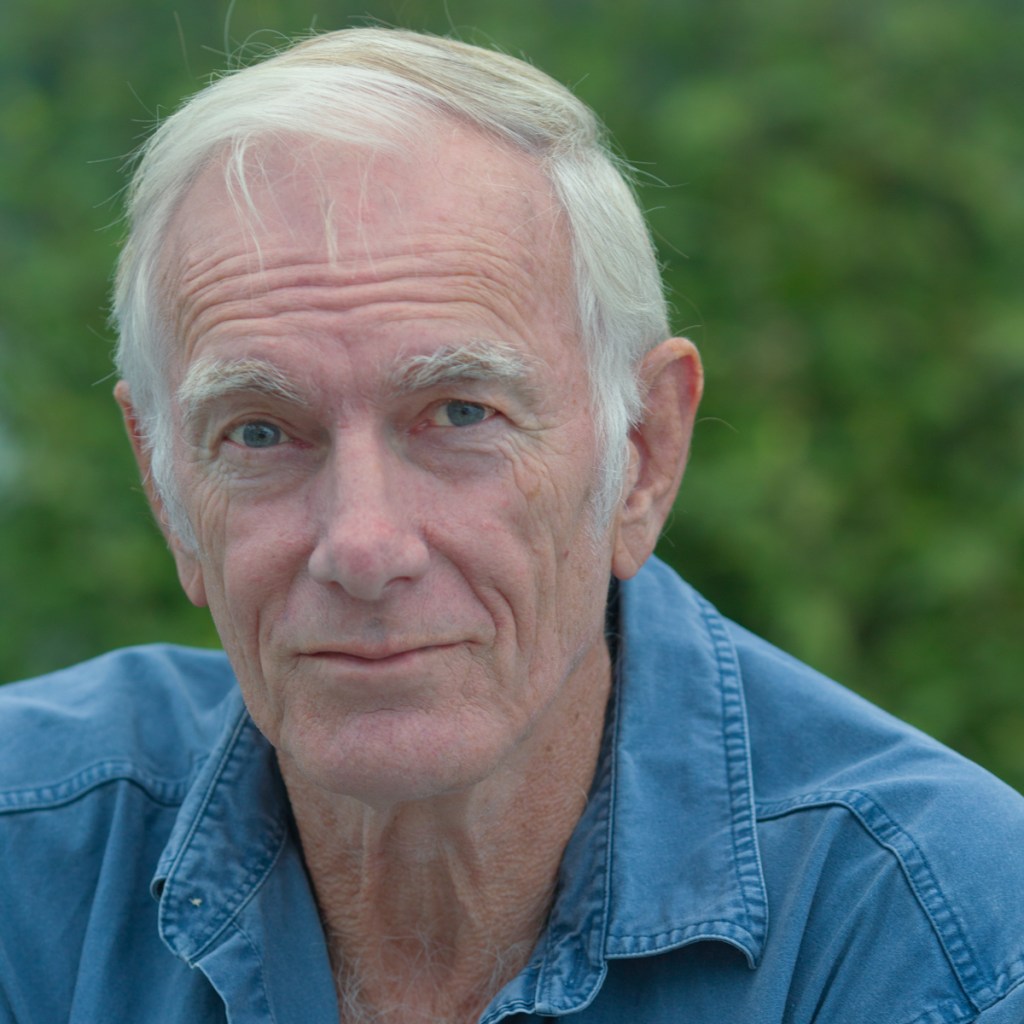

Crucible: An Interview with John Sayles about his latest novel

John Sayles is one of the great storytellers of our age. His films include such classics as Matewan (1987), Eight Men Out (1988) and Lone Star (1996). They grapple with such themes as individual and institutional corruption, moral complexity, American identity and its place in the world. While this may sound heavy, Sayles is first and foremost an entertainer: To step into any of the fictional worlds he creates is a compelling and enriching experience.

In addition to his extraordinary output in the cinema, Sayles has also had a distinguished career as a novelist since his debut work, Pride of the Bimbos, was published in 1975. In recent years he has become more prolific as a novelist, averaging a book a year. His latest work Crucible is an epic tale covering fifteen years in the history of the Ford Motor Company. It begins with the introduction of the Ford Model A car in 1927 and ends with America at war with the Axis powers in 1943, and also at war with itself as race riots burn through Detroit. In the interim we have a panoply of characters and scenes – Henry Ford policing his River Rouge plant with an ICE-like private army; Diego Rivera turning up to paint a mural; gangsters, middle managers and organised labour all jockeying for power and influence and, most fascinating of all, Ford’s disastrous attempts to establish Fordlândia, an industrial town in the Brazilian Amazon that sinks all of its inhabitants into a Heart of Darkness-style nightmare.

The rapid-growth of the Ford Company parallels the ascendancy of the United States as a world power. War brings out the full might of America’s industrial power but at what cost?

Crucible is a novel that comments on the America of today by shining a light on its past. I had the good fortune to talk to John Sayles about his latest work:

Interviewer: You have covered so many locales in your art, from Texas to Alaska to the American occupation of the Philippines, what made you pick the setting and locations of Crucible to tell this story?

Sayles: I’ve spent some time in Detroit, was very aware of the 1967 race riot there, and became very aware of it as more of a high-pressure crucible where American political and cultural forces collided than the more benign ‘melting pot’ we like to think of. When I read Greg Grandin’s Fordlandia (some producers wanted to turn it into a mini-series) the last, imperialist, part of the equation fell in for me and I started on the novel.

Interviewer: Before reading Crucible I had, rather lazily, bought into the idea that Henry Ford was an American hero. You offer a much richer and more complex portrayal of the man. When did your interest in Ford begin?

Sayles: I’d always seen Ford as the last of the great private capitalists- he and his son Edsel were the sole owners the giant international motor company- with the megalomania that kind of success and power often comes with. The more I learned about him, the more complex a man he was revealed to be- his relationship with his adoring son Edsel is really tragic.

Interviewer: In Crucible you weave a tapestry of sub-plots, from prohibition bootlegging to the doomed utopian Fordlandia scheme. How did you manage to bring all of the disparate the plot strands together?

Sayles: Detroit became a crucible because of Henry Ford- he pushed prohibition (Michigan went dry before America followed), paid black workers the same wages as white, and was fascinated with the underworld, directing his ‘enforcer’ Harry Bennett to make side deals with the local mobsters. History gives you a template and a timeline the plug your characters into, they can help tell different parts of the big story and eventually start to cross paths in interesting ways.

Interviewer: Crucible presents some stark parallels with the current political climate in the US. Does America still need men like Henry Ford or will they inevitably become tyrants?

Sayles: All of society benefits from men like Ford the tinkerer- finding a better way to do something that needs doing. But as my version of Ford says late in the novel, people aren’t machines, and any inflexible social or economic formula will eventually fall apart. Our zillionaires today are mostly interested in controlling people and living in securely guarded bubbles, though a few dare to go the Elon Musk route and start dictating how everybody should live.