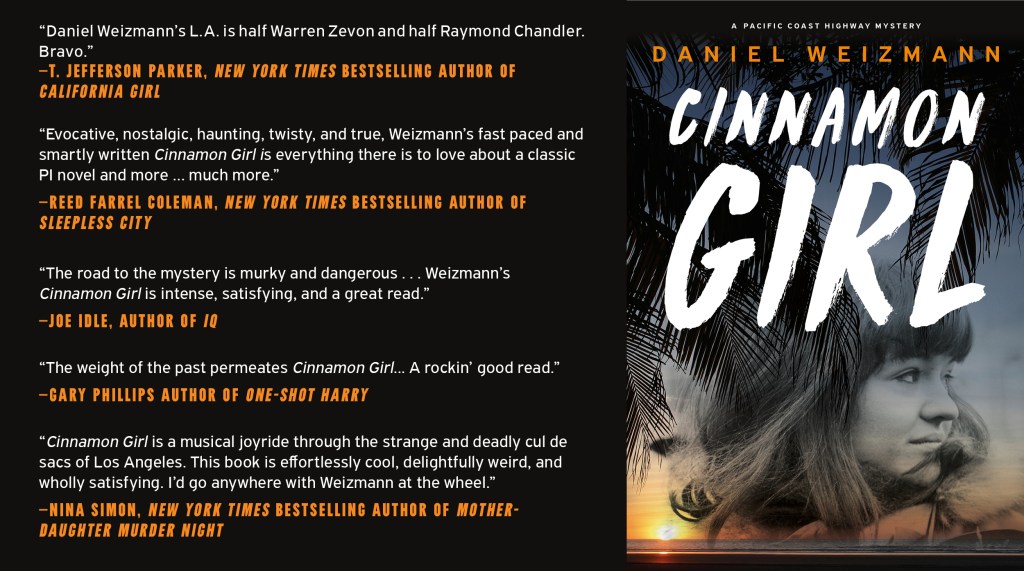

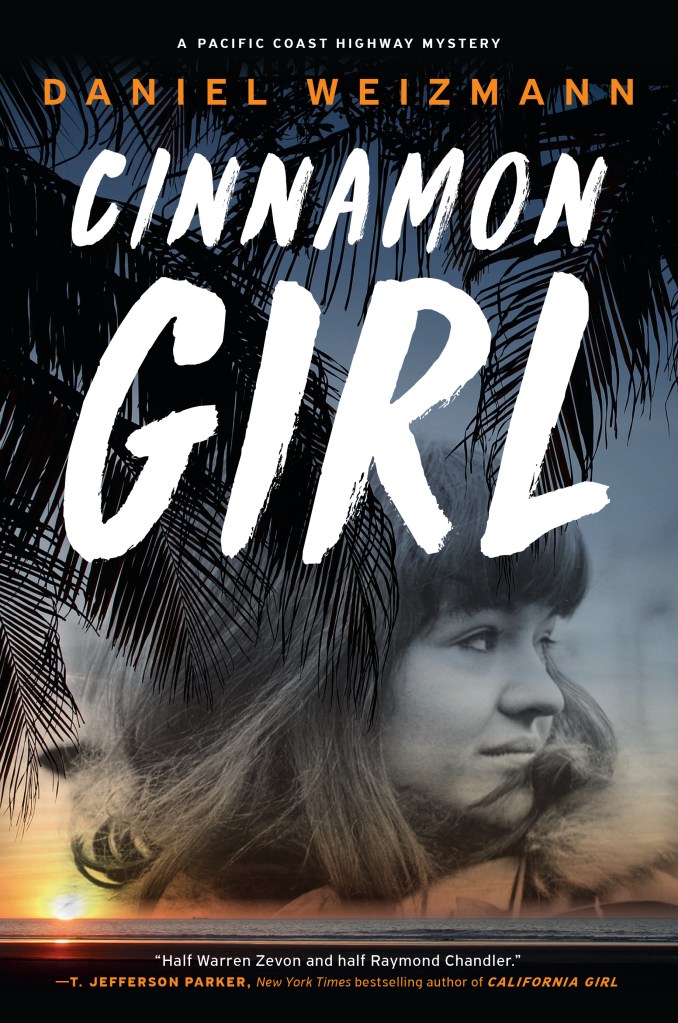

Cinnamon Girl: An Interview with Daniel Weizmann

Cinnamon Girl is the new novel by Daniel Weizmann, the second in his Pacific Coast Highway Mystery series, which stars Lyft-driver-turned-private-detective Adam Zantz.

In the first novel, The Last Songbird, Zantz gets roped into investigating the disappearance of Annie Linden, a one-time famous singer who has been burnt-out by fame. In Cinnamon Girl, Zantz investigates the dark legacy of a band calling themselves ‘The Daily Telegraph’. The story is ‘The Daily Telegraph’ could have made the big time, but Zantz finds that the truth is a lot murkier and criminally-motivated than it first appears.

I loved The Last Songbird and I’m happy to say that Cinnamon Girl is just as compelling, if not more so. Weizmann has created a terrific series and a brilliant lead character in Adam Zantz. He’s the most believable literary private detective I have encountered in years – shambolic, downtrodden, but quietly intelligent and naturally compassionate. These novels realistically capture the nostalgia-obsessed world of people on the fringes of showbiz in sun-drenched Southern California. In short, they are classic noir.

I had the pleasure of talking to Daniel Weizmann about the writing of Cinnamon Girl.

Interviewer: What would you describe as the absolute bare bones genesis of Cinnamon Girl?

Weizmann: I was born in 67’ and raised a few blocks from Hollywood Boulevard. As a young kid I was obsessed with Charlie McCarthy, you know the Charlie McCarthy doll. At one point I was in Peaches Records on Hollywood Boulevard and I saw an 8-track with a picture of the Charlie McCarthy doll. I did not realise it, but he was a radio personality. Edgar Bergen was his ventriloquist. So I assumed it was a cover for the Charlie McCarthy Show, but it was just the generic graphic for an old-time radio series. So I asked my Dad for the two dollars, or whatever it was, to buy the 8-track. And it turned out to be a double episode of The Saint with Vincent Price and Dragnet, and I just became obsessed. I got hooked on old time radio mysteries. I joined one of these little clubs which would only exist by mail through mimeographed sheets. So I joined Sperdvac, which is still around today. It’s the Society for the Preservation of Early Radio, Vaudeville and Comedy. Every three months you’d get a list of 500 things with a catalogue number, and people would trade, and often in those days it was reel to reels. So I got into all the Philip Marlowe mysteries, Sam Spade stuff. All that stuff had a radio component. So that’s how I got started.

I had these older siblings who were hippies. They were Rock N’ Roll and I was against all that. They were half-siblings. There were five of them, and I was an only child to both parents. But before my brother moved to Chicago he left me a stack of seven or eight albums. He said, ‘Just try it. You’ll never be cool enough to buy these on your own but just try it.’ I did get hooked. It was Love and Iron Butterfly, Butterfield Blues Band and a couple of others. Right after I got those records the Punk thing just exploded around me in LA. You would see them hanging out in Hollywood Boulevard. To a little kid it was scary, but I very quickly got interested in it, reading Slash magazine, Flipside, and then I became totally obsessed.

Interviewer: The books do have this musicality to them which is obviously very hard to get on the printed page. What about Addy himself – Is he a lot like you? I believe you worked as a Lyft driver like him.

Weizmann: I lived outside LA for about eighteen years, from the age of 29 to 43. And when I came back I was broke. I had very little to show for my journeys. I was divorced. I was childless. I was totally rootless and I came back to my hometown. LA is a place you have to know to love and the love is always tainted with ambivalence. When I came back, I felt like Rip Van Winkle. I was really lost. I was living in a guest house. There were cicadas or crickets, hundreds of them, on the lawn outside making a racket. All night I was driving around. Everything had changed since I was a youth, and that sense of lostness is the real Adam Zantz. I wouldn’t say we’re exactly alike but he’s that part of me.

Interviewer: One of the great things about LA is you don’t have to be famous to be constantly rubbing up against a sense of celebrity or lost celebrity. Adam isn’t famous but he runs into the songbird, Annie Linden and the band ‘The Daily Telegraph’. Did you get a sense in LA of this sense of celebrity always bombing around you?

Weizmann: Absolutely, from a very early age. My mom co-conducted group therapy with a psychologist in Beverly Hills. So when I would go there, his (the co-conductor’s) kids and me would get babysat together, and we’d be playing on the front lawn and I remember when I was 7 or 8 meeting Groucho Marx with his handlers. These two beautiful women walking him down the street when he was in his eighties. I played with John Avildsen’s kids. You knew kids of celebrities. You saw them in random places. I remember my Dad saying, oh look it’s the guy from Mission Impossible. It’s in the fabric. As you get older you know a lot of people who are aspiring to get into it. You start to see the tragic side to it. For every person who gets that role there are 199 who tried and failed. So it’s the Boulevard of Broken Dreams. It’s a do or die kinda dream, and it’s a do or die kinda place LA.

Interviewer: I think the fact it is always out of reach is what keeps you going in some ways.

Weizmann: I worked as an editor for Jill Schary Robinson, who was the daughter of Dore Schary, who ran MGM in the fifties. So she grew up around real fame. Elizabeth Taylor coming over for dinner. Bogart driving her around. The superstars of the fifties. And she said something once that blew my mind. She said, ‘People who are famous, with very few exceptions, are in a constant state of trying to hang onto it.’ They have a constant sense that if they let go of the rope somebody else is going to take their place.

Interviewer: What struck me a lot about Southern California was how addiction recovery is this huge business.

Weizmann: Just imagine how it was in the 70s and 80s. I grew up in a totally permissive environment. In high school you would do coke with your friends’ parents. It was completely unhinged. Everybody was high.

Interviewer: You mentioned Chandler. Are there any other writers that have seeped into your work?

Weizmann: Definitely. Besides Ross Macdonald, Walter Mosley, James Ellroy, P.D. James, all the crime fiction writers that I love, I have a real affinity for a certain kind of Jewish schlemiel character that you find in Saul Bellow like Herzog or Seize the Day which is an incredible novella. Or even the much older Benya Krik stories by Isaac Babel, translated from Russian. My story is… my Dad was a tough guy. He fought on the frontlines in four wars. He was raised in abject poverty in Casablanca. He fought with the French Army in WWII. He was a prisoner in Cyprus. He was a very strong guy. He even looked a little like Humphrey Bogart, and he’s the one who gave me that love of those guys because we would sit and watch The Big Sleep and all that stuff together. But whenever I would sit down to try and write a mystery I couldn’t be that because that’s not my real essence. I’m not hardboiled. Until I finally realised that my guy (Zantz) is a loser. I don’t see him as a loser but he’s somebody that this culture would deem a loser. He’s practically living out of his car. He’s barely scraping by. He’s got such a big heart that he’s almost unable to function in a cutthroat society, but it’s what makes him a good detective. He puts together the clues with his heart. I don’t think I’m criticising anyone’s work by saying I’m trying to do something with the mystery that I don’t see much of. I have great respect for all these police procedurals. I love the ones that go deep like Louise Penny. Unlike a lot of my peers, I don’t criticise the cosies either. I really enjoy them on a limited diet. But there’s something very cerebral about the mystery genre. I’m trying to make it a little more liquid.

Interviewer: It’s such a market-saturated genre that it’s very difficult to find a new angle, and I think you’ve found it. Publishers tend not to want anything too original. They want a slight re-tread of what’s come before.

Weizmann: I’ve been very blessed to have an incredible agent, Janet Oshiro, and an editor, Carl Bromley, who’s English, and I don’t think it’s an accident that he’s English. I’ll come out and say that he comes to noir with a rich sensibility. In Cinnamon Girl I’m trying to rail against the genres lean towards nostalgia. Not because I don’t get it. Quite the opposite. I’m intensely nostalgic to the point that I think it’s dangerous. So that’s what I tried to deal with in the book.

Interviewer: In the first book you have Annie Linden, this quite romantic character but also a tragic character. In the second book you have this unit, ‘The Daily Telegraph’, which I’m sure you know is the name of a right-wing newspaper here in the UK. It was interesting to think of The Telegraph as this band – they could have made it. Maybe in their heads they did make it. How musical are you? Do you play?

Weizmann: I have been in bands and was never a great asset to them, but I have the experience. I loved the camaraderie of being in a band. There was nothing like it. I imagine it’s like being a soldier in the same army. You have this united goal. Everybody has a slightly different strategy which you have to cope with, but the brotherhood of it and the relationships of it… The other thing I really experience in a band is that so many of the people in bands come from fractured families, and then they form this second family. But it doesn’t mean that it’s easy now that they are all dealing with their family stuff towards each other. The reason that it’s ‘The Daily Telegraph’ has to do with the funny Anglophile thing we have here in LA. That they would just hear something that sounds English and want to be that.

Interviewer: It’s a cool name. I assume we might be seeing more of Adam Zantz in future books?

Weizmann: I’m working on a third story now with the aim of getting him licensed, but also just dealing with him growing up a little. I would like to see where he goes. Definitely.

Interviewer: What has the reaction been to the books? Do you read the reviews?

Weizmann: I read some reviews that just knocked me out. Somebody said, this is the right hero for our time. That is so beautiful. I never would have made that assumption, but I could kind of see it. We seem to be in some state of shabby, crumbling something and Adam is trying to face that.

Interviewer: Would you consider writing something outside of this series?

Weizmann: I’d certainly consider it, but for me it’s just been such a wonderful vehicle. I feel that there’s nothing that I need to squeeze into a book that I couldn’t squeeze into these books. So there’s a third one that is in the fourth or fifth draft, and I also have the outline of a fourth one.

Interviewer: I think you’ve got the balance right with Zantz in that he’s running up against intrigue but he’s not dropping five guys per chapter.

Weizmann: That is one of the highest compliments I’ve received. I work very hard to continually reality check because the tendency in crime fiction to go over the top is, I think, a huge mistake. On yesterday’s panel (at the LA Times Festival of Books) about series fiction, Tracy Clark said something great. I’ve been thinking about it ever since. She said, ‘The art form we practice is house by house, beat by beat, one crime at a time.’ This is one of the last vestiges of narrative where you don’t have to be over the top. You don’t have to have a Marvel hero battling fifteen dragons, and everything is too loud and coming at you non-stop and it’s numbing. When it’s really great it’s human sized. When Ross Macdonald is great, nothing can touch him. He’s as good as any literature and you feel that those people are so vivid.