Lee Earle Ellroy – The Early Life of James Ellroy

Conversations with James Ellroy begins with a chronology which sets out the key dates and events in Ellroy’s life. It was my task as editor to compile this chronology. At first glance it did not seem particularly daunting as Ellroy has written two memoirs, several autobiographical essays and has discussed his life in hundreds, if not thousands of interviews. But the abundance of sources creates its own problems: there are contradictions regarding dates and places, making it apparent that some sources must contain inaccuracies that as an editor you don’t want to repeat. I also had to take into consideration that as a memoirist Ellroy tended to be vague regarding dates. I see two main reasons for this: firstly, in his early life Ellroy dropped out of high school, seldom held a job, went through periods of homelessness, struggled with alcohol and drug addictions, committed several crimes including burglary and shoplifting, and served short sentences at the Los Angeles County Jail. Given these circumstances, it is perhaps not surprising that there is a lack of documentation regarding Ellroy’s early life, and his own recollections are written in a fluid, stream of consciousness style. Secondly, Ellroy once conveyed to me that he was purposefully vague about dates, as he wanted to keep some things private. For an author who has bared so much of his soul over the course of his career it would be hard not to sympathise with his desire not to keep some elements of his life out of the public eye.

Many readers may not be aware that James Ellroy was not born with that name, but was named Lee Earle Ellroy after his father. It was a name he would come to despise feeling it sounded too much like Leroy, and this hatred of his own name typified the luckless, self-loathing man he was for much of his early life. The purpose of this article is to look at the first thirty-three years of Ellroy’s life, although I skip some events due to the constraints of limited space, my aim is to set out as accurately as possible a historical record of the often frightening and disturbing life of Lee Earle Ellroy.

Lee Earle Ellroy was born on March 4, 1948, in Los Angeles, California, the only son of Geneva “Jean” Odelia Ellroy (nee Hilliker) and Armand Lee Ellroy. Ellroy was born just over a year after the discovery of the mutilated corpse of Elizabeth Short on a vacant lot at 39th and Norton, Los Angeles, on January 15, 1947. Miss Short was dubbed ‘the Black Dahlia’ by the press, and her unsolved homicide would become one of the most enduring mysteries in Los Angeles history and a lifelong obsession for Ellroy, being the subject of perhaps his greatest work of fiction.

Ellroy’s memories of his parent’s marriage suggest a very unhappy union: they fought, drank too much and had affairs. In an interview with Nathaniel Rich, Ellroy said, ‘I don’t remember a single amicable moment between my parents other than this: my mother passing steaks out the kitchen window to my father so that he could put them on a barbecue.’ Ellroy’s parents divorced in 1954, and Jean retained primary custody of her son. The relationship between his parents would continue to be hostile, and young Ellroy often found himself caught in the middle of their disputes. In 1958 Jean and her son moved to a new home in El Monte, just outside Los Angeles. Although his mother had promised him a bigger, nicer house, young Ellroy was shocked at how small and dilapidated their new accommodation was. On June 22, 1958, the body of Geneva Hilliker Ellroy was found in the shrubs outside of Arroyo High School. She had been strangled to death. The police began a murder investigation, but the case was never solved. Young Ellroy had been with his father the weekend of his mother’s death. They had been to the cinema to watch The Vikings starring Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis. When he arrived back at his mother’s house, he saw several police cars, and as he describes in his memoir My Dark Places, ‘A man took me aside and kneeled down to my level. He said, “Son, your mother’s been killed.”’

For his eleventh birthday on March 4, 1959, Ellroy’s father gave him two books, an anthology The Complete Sherlock Holmes and Jack Webb’s The Badge. The Badge contained a ten page synopsis on the Elizabeth Short murder case and Ellroy was immediately fascinated. He saw the parallels between the Elizabeth Short case and his mother’s unsolved murder, and grew a greater understanding of his mother as a result. Although he could not know it at the time, the unsolved homicide would become the subject of his seventh and arguably greatest novel The Black Dahlia (1987).

Ellroy’s formal education was hindered by his increasingly erratic behaviour. He attended John Burroughs Junior High School from 1959 to 1962 and then Fairfax High School from 1962. Fairfax High was predominantly Jewish and regardless of what his real views may have been, Ellroy would say and do almost anything to get attention. In his interview/article ‘Doctor Noir’ Martin Kihn records that ‘he [Ellroy] wrote a song criticizing American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell to impress a girl.’ However, he also engaged in outrageous acts of anti-semitism, joining the American Nazi Party, buying Nazi paraphernalia and singing the Horst Wessel song. In 1965, Ellroy was expelled from Fairfax High for fighting and truancy. Armand Ellroy’s health had been deteriorating for some time. On November 1, 1963, he suffered the first of several strokes. The young Ellroy became his father’s caregiver. Despite this, when he was expelled from school, Ellroy asked his father for permission to join the US Marines. Armand Ellroy refused, but he did allow Ellroy to join the regular army. Thus, in May 1965 Lee Earle Ellroy had a very brief period in the US Army stationed in Fort Polk, Louisiana, assigned to Company A, 2nd Battalion, 5th Training Unit. Ellroy was particularly unsuited to army life, Kihn describes his arrival:

While taking the Army oath, Ellroy realized he was making a big mistake. He started faking a nervous breakdown by stuttering, then tearing his clothes off and running naked through the Fort Polk, Louisiana, reception station.

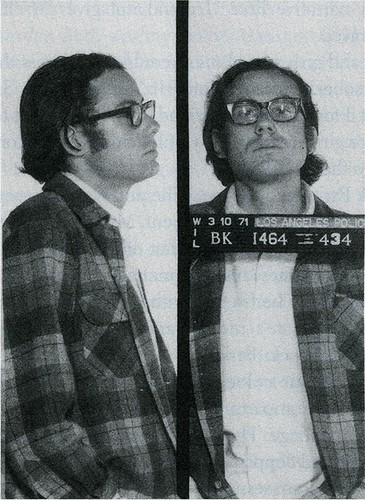

Ellroy’s outrageous behaviour managed to convince an army psychiatrist to recommend an immediate discharge. Ellroy’s army career lasted less than a month; his father suffered another stroke and Ellroy flew back to LA to visit him in hospital. He died on June 4, 1965. Armand Ellroy’s last words to his son were ‘Try to pick up every waitress who serves about you.’ After his father’s death Ellroy’s life steadily fell apart. He seldom worked or had money. He cashed his father’s last three social security checks, and also received money from his mother’s insurance policy administered by his aunt in Wisconsin. He worked briefly for a psychic passing out handbills, and also found work in a pornographic bookstore, but was fired for stealing money from the till. 1966 to 1969 were some of the darkest years of Ellroy’s life; he went through periods of homelessness, sometimes sleeping in the parks in LA. He became an alcoholic, drinking copious amounts of scotch and Romilar CF cough syrup, and a substance abuser of amphetamines and Benzedrix inhalers. Voyeurism was Ellroy’s other all-consuming addiction. He would break into to the houses of young women who lived in the wealthy Hancock Park area of LA. His overriding purpose was sexual voyeurism, not burglary for money. He would search through the clothes drawers and sniff women’s panties. He would make himself a sandwich and pour a drink, before leaving the house and carefully covering his tracks. The Manson family murders in 1969 led to a paranoid atmosphere in LA and the arrival of several private security firms which patrolled Bel-Air and Hancock Park. The increased risk led Ellroy to stop breaking into houses. However, his list of petty crimes continued and led to a series of arrests and short term stints in the Los Angeles County Jail. Although he has given differing accounts as to the number of times he was arrested, Ellroy’s police record lists fourteen arrests between 1968 and 1973 for offences such as shoplifting and driving under the influence. Martin Kihn describes Ellroy’s first arrest as being quite dramatic, ‘someone reported having seen Ellroy sneaking into a deserted house, and a team of L.A. cops barged in with shotguns and arrested him.’

Between 1975 and 1977 Ellroy’s health was in a dangerously poor condition; he suffered two bouts of pneumonia and almost died of a lung abscess. He also had a nervous breakdown and was diagnosed with the rare condition post-alcoholic brain syndrome. These health scares persuaded Ellroy to clean up for good. He entered Alcoholics Anonymous and quit drinking. In 1977 he began working as a caddy at the Hillcrest Country Club but was quickly sacked after fighting with a fellow caddy. He then began a slightly longer tenure at the Bel-Air Country Club, and it would be caddying that provided the inspiration for his first novel. One of the less dramatic features of the life of Lee Earle Ellroy was his growing love of crime fiction, which began as a child. He started off reading the Hardy Boys and Nero Wolfe novels, later graduating to Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Mickey Spillane, Ross Macdonald and Joseph Wambaugh. Even during his periods of homelessness, Ellroy devoured crime fiction, often sitting in a library for hours reading through detective novels and drinking scotch. Crime fiction would be the subject of his first novel, Brown’s Requiem, (Ellroy’s preferred title was ‘Concerto for Orchestra’ but this was later changed at his publisher’s insistence). In the novel, the protagonist Fritz Brown is an ex-cop, repo-man and low-rent private eye. Ellroy has described the novel as autobiographical:

Here’s a guy who looks exactly like me, has a German-American background, likes classical music, came from my old neighborhood, gets involved with a bunch of caddies. All that’s me.

Writing the novel was a challenge, as Ellroy described in an interview with Fleming Meeks, it began with a prayer on the grounds of the Bel-Air Country Club on January 26, 1979,

‘God,’ I said, ‘would you please let me start this fucking book tonight?’ And I’ve been at it ever since.”

Ellroy did not own a typewriter and the novel was handwritten. His writing sessions were often conducted on a bench at the Bel-Air, or in the caddyshack while the other caddies were sat around playing card games. Once the novel was completed, Ellroy quickly found an agent who sold the manuscript to Avon for $3,500. Brown’s Requiem was published in 1981, and upon publication Ellroy changed his first name and moved across country to Eastchester, New York, where he continued his writing career while working as a caddy at the Wykagl Country Club. As Ellroy explained in an interview with Craig McDonald, when changing his name he chose the name James from the pseudonym ‘James Brady’ which his father had used. ‘It’s just a simple name that goes well with “Ellroy.”’

Lee Earle Ellroy officially ceased to exist. James Ellroy would become one of the greatest American crime writers.

Conversations with James Ellroy is available to buy on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Trackbacks

- James Ellroy – What’s in a Name? | The Venetian Vase

- Early Ellroy | The Venetian Vase

- The Two Men Who Saved James Ellroy’s Career | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy Day? – January 26 | The Venetian Vase

- AWOL | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy in Manchester: In my Craft or Sullen Art | The Venetian Vase

- Albert Teitelbaum – The Man Who Sued James Ellroy | The Venetian Vase

- Noir City comes to Denver | The Venetian Vase

- Days of Smoke by Woody Haut – Review | The Venetian Vase

- Ellroy Contradictions | The Venetian Vase

- Rita Hayworth and the Armand Ellroy Redemption | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy’s THIS STORM – Review | The Venetian Vase

- ZaSu Pitts and Jean Ellroy: Kindred Spirits? | The Venetian Vase

- Aly Khan, Armand Ellroy and a Royal Biography | The Venetian Vase

- The Mystery of Jean Hilliker’s First Marriage – Solved | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy’s Wisconsin Police Gazzette: The Long Halloween | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy: From Author to Character | The Venetian Vase

- James Ellroy and Steven Parent: A Tale of Two El Montes | The Venetian Vase

- The Murder of Jean Ellroy – The Search for Answers | The Venetian Vase

- A James Ellroy Playlist: Rags to Riches | The Venetian Vase

Great stuff Steve! Congratulations! Ellroy is one of my all time favorite writers and this looks like a great read. Good luck- I hope it sells a million.

Thanks David,

I really enjoyed putting the book together so I’m hoping people will enjoy reading it.

Steve

James Ellroy is a very scary, unhinged man. I saw a Bio of him and he evens sounds scary. I never understood the sexual connection along with the hate for his Mother? I think he could be very dangerous.

Jere,

I think Ellroy is often performing when he is at his most unhinged. It takes enormous discipline to hone the sort of writing talent he possesses. Although he has been through traumas few of us could imagine, my personal experiences of him make me think that he is kind and encouraging to young writers and not in the least bit scary.

Steve

I was wondering how you obtained copies of his arrest records from the LAPD? I was interested in obtaining the detectives’ reports on the death of actor Nick Adams, who died on Feb. 7, 1968. A police representative told me the LAPD routinely destroys documents after 25 years, unless they pertain to a criminal conviction that might still be in the appeals process

Hi,

I viewed Ellroy’s arrest records at the Ellroy archive, Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina. You must seek permission from Ellroy before you view any documennts in his archive. I’m not sure what the LAPD procedure is ordinarily but Ellroy has a very strong relationship with them now so perhaps they made an exception for him. His mugshot has also been reprinted in at least one of his books.

Best wishes,

Steve