For the latest episode of Ellroy Reads, I take a look at Steve Fisher’s classic novel I Wake Up Screaming. A critical and commercial hit at the time, I Wake Up Screaming was published in two versions and was adapted into film twice. The first adaptation is considered one of the very first film noirs. I discuss Ellroy’s admiration for Fisher’s writing and how releasing the novel in two versions may have loosely inspired some of Ellroy’s recent business decisions as a writer.

Enjoy the episode. Subscribe to the channel if you like the content.

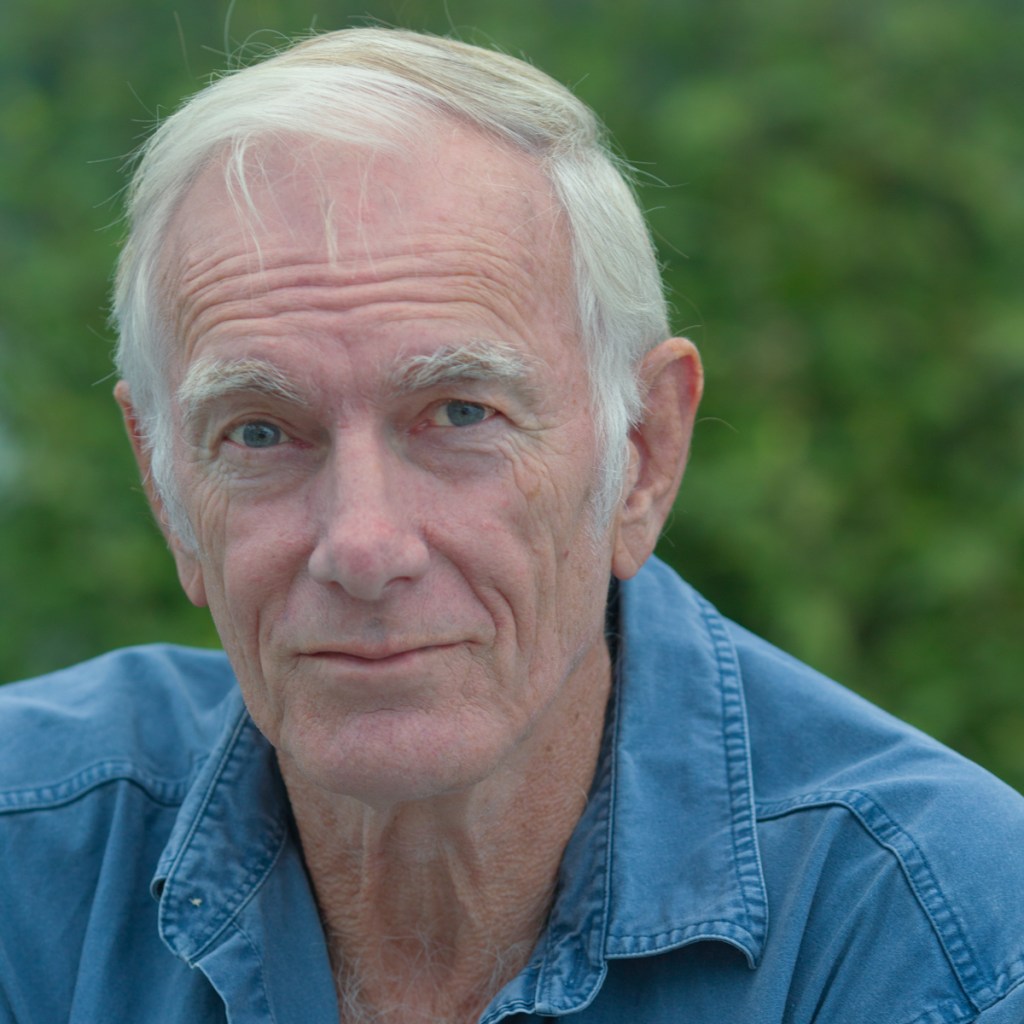

James Ellroy – Still Swinging at Seventy-Eight

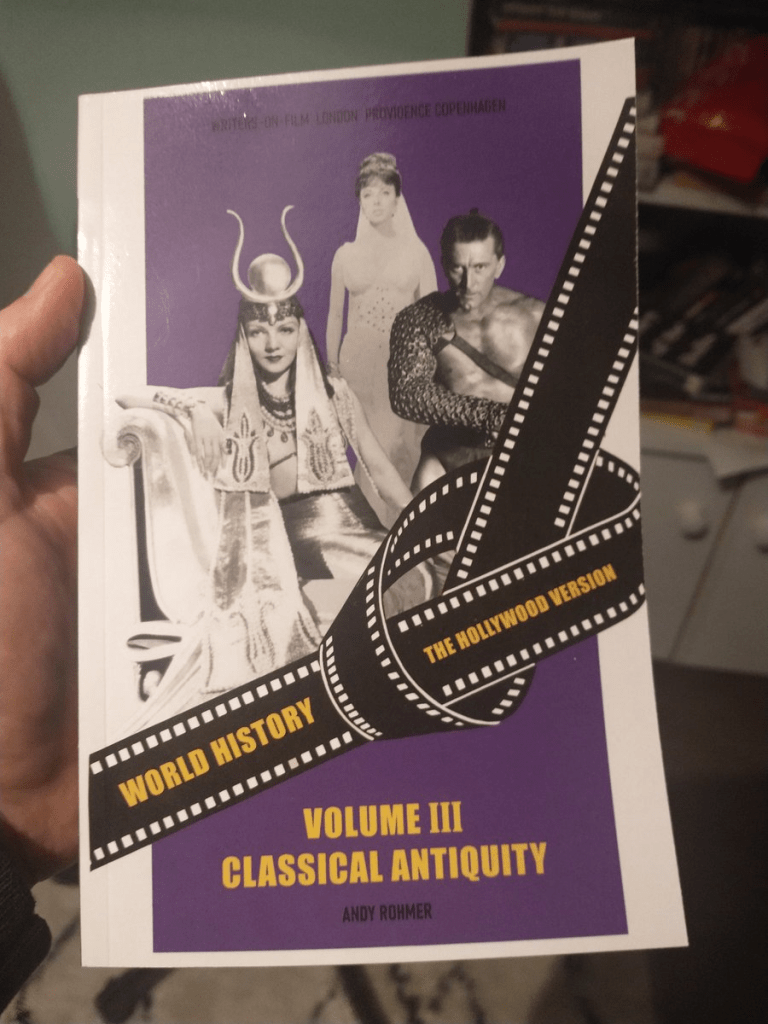

March 4th is James Ellroy’s birthday. The Demon Dog of American Literature is seventy-eight years old today. To mark the occasion, Britton Summers invited me onto his YouTube show Britton’s Hangout Hour to discuss Ellroy’s life and my Edgar-Award winning biography of him, Love Me Fierce in Danger: The Life of James Ellroy.

I had a blast talking to Britton about all things Ellroy-related. Enjoy the episode.

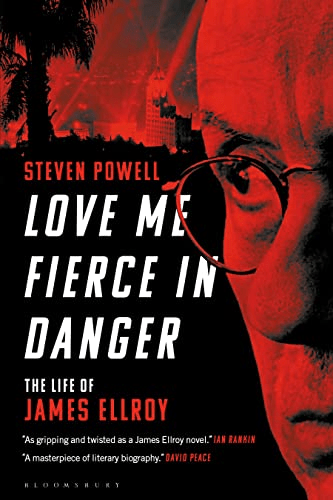

2026 looks set to be a big year for readers who are interested in the (Holly)weird and wonderful life of Fred Otash. Otash, the Private Eye to the Stars, is the subject of the recently published biography The Fixer by Manfred Westphal and Josh Young. Additionally, this Summer, James Ellroy’s latest novel Red Sheet, in which Otash is the leading character, is set to be published. So for the latest episode of Ellroy Reads, I decided to review The Fixer and examine just how much it is a genuinely factual account of Otash’s life. I compare the book to the stories Ellroy told me about Otash. Ellroy made no bones about how the Otash of his novels is a fictional portrayal of the man, but it does seem that Westphal, backed by Otash’s daughter Colleen, is in a tug of war with Ellroy as to who controls Otash’s legacy of Hollywood investigations.

It’s a fascinating literary dispute. Enjoy the episode and don’t forget to subscribe to the channel, as this helps me to keep producing content.

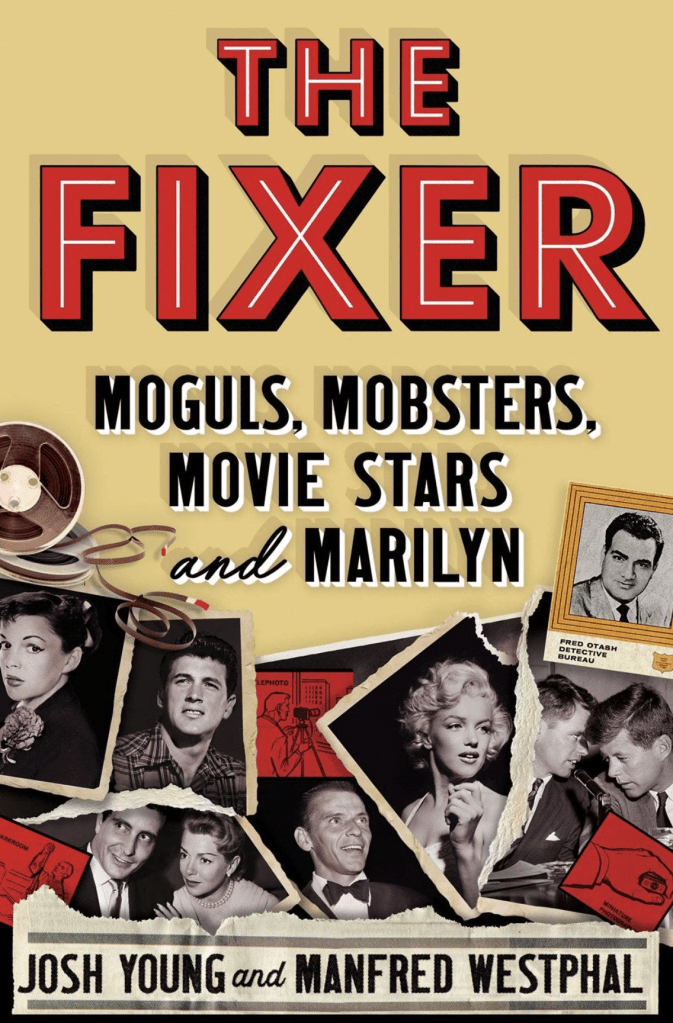

World History: The Hollywood Version – Classical Antiquity – Review

Andy Rohmer new series of books, World History: The Hollywood Version, is a delightfully witty insightful stroll through the annals of history and how Hollywood has adapted it, twisted it and sometimes downright changed it to suit its needs. I say this is a new series by Rohmer as his previous series, Writers-on-Film, was also a must-read critique of the intersection of literature and Hollywood.

The latest book in the series explores how Tinseltown has portrayed the period of Classical Antiquity (490 BCE to 476 CE) on film. One might have assumed the sword-and-sandal epics were a thing of the past, but Rohmer scrupulously goes through a number of recent examples – Alexander, Gladiator, Agora, The Eagle. Many of these films put bone-headed actions sequences before thoughtful depictions of the period, but Rohmer does reserve praise Neil Marshall’s Centurion for its ‘(historically accurate) portrayal of matriarchy and the first feminist sword-and-sandal after years of closet gayness’. Of course, the 1950s were probably the apex of Classical Antiquity being portrayed or mutilated, if you will, on film and Rohmer gives us plenty of analysis and behind the scenes content on such Sunday afternoon Telly staples as The Robe, Ben Hur and Demetrius and the Gladiators. However, if any reader feels protective of these types of films I should warn you that Rohmer doesn’t hold back on their faults. Of Charlton Heston, a stalwart of these types of epics, Rohmer criticises his ‘atrocious diction, rolling r’s and spitting syllables like a Method actor high on coke.’ All of the book is engrossing, and the cattier the review, the more fun it is to read.

All in all, this is a compelling volume which enhances the overall series. Reading it will leave you hungry for Rohmer’s take on the next Hollywood epoch.

Fer-de-Lance by Rex Stout reviewed for Ellroy Reads

The Nero Wolfe series by Rex Stout feature some of the most popular and enduring mystery novels in American literature. The character of Nero Wolfe – sedentary, erudite, eccentric, a gourmet – might seem a world away from the hardboiled figures in James Ellroy’s fiction. However, in the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I discuss some of the connections between the Nero Wolfe series and Ellroy’s life and work.

If you’ve been enjoying watching Ellroy Reads every Sunday, then please hit that subscribe button as this helps me to continue producing content for the channel.

The Union Station Massacre by Robert Unger, reviewed for Ellroy Reads

In the latest episode of Ellroy Reads, I discuss Robert Unger’s true crime tale The Union Station Massacre: The Original Sin of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. The Kansas City Massacre occurred on June 17, 1933, and lead to the death of four lawmen and one gang member. The official version of events is that the shootout happened when three gang members tried to arrange the escape of Frank ‘Jelly’ Nash, an outlaw and bank robber who was being returned to Leavenworth prison after escaping three years earlier. But Unger questions the entire FBI narrative that has grown out of the case, and he is particularly indignant about how Hoover saw it as the perfect publicity opportunity and power grab for the Bureau.

Much of Unger’s thinking on the case inspired James Ellroy’s fictional portrayal of J. Edgar Hoover. I hope you enjoy the episode and do remember to subscribe, share, comment on and like the content. Thanks.

The Casino by Iain Ryan – Review

Iain Ryan is one of the most promising new writers to emerge from the Australian crime genre. His novels such as The Strip and The Dream have brought the 1980s Gold Coast setting to life in noir fiction. With his latest novel, The Casino, Ryan has really hit his stride. This is his best novel yet, and one that could make him a big name.

In the novel, The Saturn is the titular casino. It’s run by Queensland Mob Boss Colleen Vinton, and is a hangout for crooked cops, desperate gamblers and incurable grifters. It becomes the refuge of private detective Ewan Hayes, who is tasked with escorting Grace Holloway, the daughter of a Melbourne journalist, out of town to escape criminal elements. Hayes takes on another case while he’s away, to find a missing person named Herb Fleming, and he discovers that Grace is quite a formidable investigator herself. Meanwhile, the Queensland police forces are still knee deep in corruption. Detective Lana Cohen is a rare example of a copper you can trust. Wrestling with demons from her past she is hoping for a quiet life with her new boyfriend, but the grisly discovery of a severed head on Nobby Beach plunges her right back into the most dangerous form of police work. There are other elements at play, including the activities of a particularly violent ring of shoplifters and whether these crimes connect to the murder of several police officers. In The Casino, a police badge is no guarantee that the criminal underbelly will regard you as untouchable.

While these plot strands might seem convoluted, the author weaves them together with considerable skill and demonstrates a real flair for the language and milieu of the Gold Coast. No one knows this setting better than Ryan. The Casino is a gripping read from start to finish, and I’m putting my stack of chips on Iain Ryan becoming the next big star of crime authors from Down Under.

The Enchanters by James Ellroy – reviewed for Ellroy Reads

While we await the release of James Ellroy’s new novel Red Sheet, to be published later this year, I thought it would be interesting to revisit Ellroy’s previous novel The Enchanters. I was spending a lot of time with Ellroy, as his biographer, while he was writing The Enchanters and, in the video below, give an in-depth viewpoint of his process, his relationship with the real-life leading character Fred Otash, and how Ellroy’s publishing colleagues perceived the novel.

The Enchanters represented a big change in Ellroy’s writing plans, essentially abandoning, or reformulating if you prefer, his ambition to write a Second Los Angeles Quartet. I hope you enjoy the show. You won’t find this content anywhere else, so why don’t you subscribe to the channel and you’ll never miss an episode.

Exodus by Leon Uris – Reviewed for Ellroy Reads

For the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I look at Leon Uris’s novel Exodus. An epic tale of the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel, Exodus was the biggest bestseller in American literature since Gone With The Wind, but as with Margaret Mitchell’s novel of the American Civil War, Exodus is now viewed with increasing scepticism due to a number of controversial factors in the book.

I discuss these factors as well as a number of controversial issues surrounding James Ellroy’s life. I hope you enjoy the episode, and do remember to subscribe, share and like the content. Shalom.

Crucible: An Interview with John Sayles about his latest novel

John Sayles is one of the great storytellers of our age. His films include such classics as Matewan (1987), Eight Men Out (1988) and Lone Star (1996). They grapple with such themes as individual and institutional corruption, moral complexity, American identity and its place in the world. While this may sound heavy, Sayles is first and foremost an entertainer: To step into any of the fictional worlds he creates is a compelling and enriching experience.

In addition to his extraordinary output in the cinema, Sayles has also had a distinguished career as a novelist since his debut work, Pride of the Bimbos, was published in 1975. In recent years he has become more prolific as a novelist, averaging a book a year. His latest work Crucible is an epic tale covering fifteen years in the history of the Ford Motor Company. It begins with the introduction of the Ford Model A car in 1927 and ends with America at war with the Axis powers in 1943, and also at war with itself as race riots burn through Detroit. In the interim we have a panoply of characters and scenes – Henry Ford policing his River Rouge plant with an ICE-like private army; Diego Rivera turning up to paint a mural; gangsters, middle managers and organised labour all jockeying for power and influence and, most fascinating of all, Ford’s disastrous attempts to establish Fordlândia, an industrial town in the Brazilian Amazon that sinks all of its inhabitants into a Heart of Darkness-style nightmare.

The rapid-growth of the Ford Company parallels the ascendancy of the United States as a world power. War brings out the full might of America’s industrial power but at what cost?

Crucible is a novel that comments on the America of today by shining a light on its past. I had the good fortune to talk to John Sayles about his latest work:

Interviewer: You have covered so many locales in your art, from Texas to Alaska to the American occupation of the Philippines, what made you pick the setting and locations of Crucible to tell this story?

Sayles: I’ve spent some time in Detroit, was very aware of the 1967 race riot there, and became very aware of it as more of a high-pressure crucible where American political and cultural forces collided than the more benign ‘melting pot’ we like to think of. When I read Greg Grandin’s Fordlandia (some producers wanted to turn it into a mini-series) the last, imperialist, part of the equation fell in for me and I started on the novel.

Interviewer: Before reading Crucible I had, rather lazily, bought into the idea that Henry Ford was an American hero. You offer a much richer and more complex portrayal of the man. When did your interest in Ford begin?

Sayles: I’d always seen Ford as the last of the great private capitalists- he and his son Edsel were the sole owners the giant international motor company- with the megalomania that kind of success and power often comes with. The more I learned about him, the more complex a man he was revealed to be- his relationship with his adoring son Edsel is really tragic.

Interviewer: In Crucible you weave a tapestry of sub-plots, from prohibition bootlegging to the doomed utopian Fordlandia scheme. How did you manage to bring all of the disparate the plot strands together?

Sayles: Detroit became a crucible because of Henry Ford- he pushed prohibition (Michigan went dry before America followed), paid black workers the same wages as white, and was fascinated with the underworld, directing his ‘enforcer’ Harry Bennett to make side deals with the local mobsters. History gives you a template and a timeline the plug your characters into, they can help tell different parts of the big story and eventually start to cross paths in interesting ways.

Interviewer: Crucible presents some stark parallels with the current political climate in the US. Does America still need men like Henry Ford or will they inevitably become tyrants?

Sayles: All of society benefits from men like Ford the tinkerer- finding a better way to do something that needs doing. But as my version of Ford says late in the novel, people aren’t machines, and any inflexible social or economic formula will eventually fall apart. Our zillionaires today are mostly interested in controlling people and living in securely guarded bubbles, though a few dare to go the Elon Musk route and start dictating how everybody should live.