An Interview with Craig McDonald: The Hector Lassiter Series

Craig McDonald is an author and journalist. He has written fourteen novels, including, to date, nine books in the award-winning Hector Lassiter series. I have kept up a correspondence with Craig these past few years as we are both avid readers of James Ellroy. I’m also a massive fan of the Lassiter novels, and when Craig agreed to be interviewed by me, he also kindly supplied an advance copy of the final novel in the Lassiter series, the forthcoming Three Chords and the Truth. If you are not already initiated, I hope this interview will persuade you to start reading the Lassiter novels. They are compelling, thrilling and darkly humorous. Lassiter is a brilliant creation– a crime writer who learned his trade with Ernest Hemingway and the Lost Generation in Paris in the 1920s. He is also a man who seems dangerously prone to violent intrigue, doomed love affairs, tragic marriages and military campaigns (he’s a veteran of the Punitive Expedition, World War One, the Spanish Civil War and World War Two). Lassiter witnesses history unfolding and, occasionally, has a role in shaping it course. With Three Chords and the Truth, Craig McDonald has crafted a remarkable coda to the series. Here’s the transcript of our conversation:

Interviewer: Hector Lassiter made his first appearance in your short story ‘The Last Interview’. When you were writing, what were your thoughts about developing the character because it reads very differently from the later novels?

McDonald: There was a contest, actually, and I was not really published at all in terms of fiction or even really non-fiction. It was called ‘High Pulp’ and it was supposed to be for the Mississippi Review, and they asked for a hybrid of literary approach to the short story but through a pulp prism. So I was thinking a lot about James Crumley at that time, particularly The Last Good Kiss, which is probably one of my favourite novels in the genre, and I’d been corresponding with the Irish crime writer Ken Bruen. He’d been talking about Crumley and how as the series unfolded Crumley had two male characters as his protagonists (Milo Milodragovitch and C.W. Sughrue), but they never really aged in a realistic way, and we thought it would have been so much richer if they had. So when I approached ‘The Last Interview’, I was thinking of James Crumley and sort of writing a man who’s at the end of his life. And I was thinking obviously of Ernest Hemingway, particularly his short story ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’, which is about a man dying of gangrene about to lose a leg. And when you know that, reading ‘The Last Interview’ you see the Hemingway influence even more heavily. It was a one-shot in my mind, so I didn’t write with any kind of open-ended notion of ever returning to the character. And the Review picked it up. It appeared in print. It got picked up in some anthology, and by that time, I had secured a literary agent. And she was shopping some things around without a lot of success, and I got this notion of writing a book about the stolen head of Pancho Villa. And somewhere within the first fifteen minutes of thinking about that, I decided that character from the short story should come back and be the protagonist of the novel. I think at that point he began to move in a different direction, as you said, from the character we meet in the short story: a bit more cultivated, not quite as sulky, a bit more of a bon vivant than the man in the bed who’s dying in ‘The Last Interview’.

Interviewer: Yes, I thought he was quite different– quite embittered in ‘The Last Interview’, as many people would be in a state of extreme illness. It seems like there’s been a number of transitions because you transitioned between ‘The Last Interview’ and Head Games. Head Games is a wonderful novel. The last third of the novel, particularly, is very different from the last third of any other novel in the series. You described how you intended it to be a ‘fake out’. Was it Crumley who you were trying to imitate for the bizarre denouement for that novel?

McDonald: A little bit. I was about three-quarters of the way through Head Games when I already had a notion for writing what would be the follow-up, and I guess at this point it bears saying that I wrote the novels in a certain sequence with the idea that they would appear in that sequence. The series was very unusual in that I wrote almost the entire series before we actually published the first book, so I had a definite arc and then, unfortunately through the publication of the books, editors would read them and cherry pick, so they ended up selling them and having the books published in a radically different sequence than I envisioned them originally appearing. So it creates some confusion, but Head Games was the original novel in the series that I wrote. It was the first one published and it was inspired partly by James Sallis’ series: the detective/writer/educator Lew Griffin. His series of novels, I think there are about five, maybe six, are very unusual in that it’s very metafictional. It’s very self-aware and the end of his series, without spoiling it, literally rips the carpet out from under you as the reader and forces you to think about the entire series again with this radical ending when a different narrator steps in. And my conceit through the Hector Lassiter novels, which are written in various voices as you’ve seen– first-person, third-person, variations therewith– was that regardless of how they were framed they were really secretly being written by Hector himself, and I kind of knew that as I was going into Head Games. I would take everything in one direction and then move it in a different direction, headed towards that last book in the series, which is the only one yet to appear at this time.

Interviewer: Yes, can I come back to that metafictional point a bit later on. Let’s talk a little bit about Hector. I’m quite taken by this idea that he looks a lot like William Holden because I’m a huge William Holden fan. I think he’s a marvellous actor. There’s a quote about William Holden. I don’t know who said it, ‘William Holden, you can see the map of America on his face.’ I’m wondering, did that quote mean anything to you when you chose this Holden likeness?

McDonald: Yes, I saw him as William Holden as I was writing Head Games. Probably, when I was writing the short story he was some sort of bearded blend of Crumley and Hemingway. James Crumley, quite frankly, is kind of the Ernest Hemingway of crime writers in terms of his larger than life persona. He felt an obligation, much to his detriment and eventual ill-health, to be the last guy in the bar, and the man who could clear a bar, and that sort of thing. I saw Hector as I was writing the novels as much more of a polished, very masculine man but a ladies’ man, and someone who is extremely emblematic of just the American spirit of that time. And I always had a real fondness for William Holden. He was certainly someone who was well-travelled, and that was something I saw Hector as too. Someone who could move comfortably in different places. Whether he be in Europe or in Texas, he is essentially that same man – the quintessential American.

Interviewer: I think there was an element of tragedy to William Holden in that he’d be about twenty years Hector’s junior, and he died relatively young.

McDonald: Yes, he fell in his apartment alone while drinking and hit his head on a table and, rather characteristically, he tried to administer his own first aid to an ultimately fatal head injury. He was somebody who had definite issues with alcohol, and he aged himself so dramatically. I suppose this was about 1964-65, you start to see him really physically showing the ravages of drinking. He probably looked twenty years older than he was at the time of his death.

Interviewer: Back to Hector as a character, I’m just thinking about some of his views, and it strikes me that he’s gregarious, and he seems to know everyone but he has quite strong opinions about people like me. He doesn’t like critics and, in Print the Legend, not just critics but scholars as well. Where do you stand on the symbiotic relationship between novelists and critics?

Interviewer: Back to Hector as a character, I’m just thinking about some of his views, and it strikes me that he’s gregarious, and he seems to know everyone but he has quite strong opinions about people like me. He doesn’t like critics and, in Print the Legend, not just critics but scholars as well. Where do you stand on the symbiotic relationship between novelists and critics?

McDonald: I’ve had severely rough reviews from people, who I think are critics, who actually think that I hate critics! I truly don’t. I was a book reviewer for a number of years before I began to publish myself, and I was an English major. I sat there and wrote long, very detailed, explicated pieces on literature. I think it’s a very noble calling. I think that ideally, and I think I say this a bit in Print the Legend, through the voice of the young aspiring female writer who’s married to a critic – a rather awful, sour critic – Hannah Paulson. She’s talking about the fact that there is a symbiotic relationship, and in the most constructive form, critics and authors, if they’re listening, can establish a dialogue. A tacit dialogue, I suppose, it’s not explicit, obviously, where criticism can inform and help guide a writer. I was thinking of Hemingway too, because Hemingway is a recurring character in the Hector series. He’s Hector’s best friend and they go through Paris as aspiring writers together. Hemingway, I’m reading his letters, and he was very strategic and very smart about critics he courted in the early portion of his career, and was sending them novels. He valued people like Edmund Wilson, and some others of that era who were serious critics and steeped in the canon and really wrote very intelligently about fiction. Then by the 1950s, Hemingway is sending letters threatening to sue critics and scholars who were going after him. I think also with Hector, because he is a popular writer, he probably has a certain amount of resentment that he doesn’t get serious critical attention. The closest thing he would have had would have been Anthony Boucher in the New York Times, who was the lone critic in the intelligentsia who gave any kind of serious attention to genre writing.

Interviewer: Yes, that is interesting because the first Hector novel chronologically is One True Sentence with the Lost Generation, and you might think that some of those writers are a bit lost themselves. The antagonists in that novel are called Nadaists, and you tend to have these quite sinister and villainous and deplorable people gathered round ideologies or aesthetic movements: Nadaists or Surrealists or even the Mafia in The Running Kind is a kind of law unto itself. It has its own rules and codes. Is it partly send up, or do you find there’s something genuinely menacing about these kind of aesthetic movements?

McDonald: I would say it’s more send up than anything else. I’m more fascinated by the idea of groups of people doing things with insidious intent because I think that’s far more skin-crawling than the lone wolf, aberrational villain or antagonist. I set certain private goals for myself across the series, and a lot of it was directed towards looking at the movements in art through Modernism and Dadaism which is really what nada is in a sense. It’s a very nihilistic kind of philosophy moving into Surrealism. As we go into Print the Legend, at that point you’re starting to move into metafiction, and moving towards Deconstructionism, and all of these ‘isms’ that really if you’re an artist or a writer who has any scope of career — and I deliberately have Hector born on January 1, 1900, so that he basically comes in with the century and he takes you through that century — you have to cope with all of those ‘isms’ in terms of trying to remain relevant, and I think you come to resent them a lot if you’re the kind of writer Hector is. He’s sort of on the margins. He set out in One True Sentence: he’s there in Paris trying to write a novel and he’s just writing the same thirty or forty pages over and over again because he’s just not writing to his passions or in the direction he’s meant to, and then as soon as he starts writing the so-called ‘genre novels’, he finds his voice and he’s off on his career. With each book I was taking in different things that I wanted to touch on: One True Sentence is really about writing for the most part; The Great Pretender, Orson Welles, that’s about radio and mass communication coming into the world and how it affects things; Roll the Credits is film; The Running Kind has a sort of pioneer, birth of television air about it. In The Running Kind, it’s mentioned that television sales for the first time spiked because of the televised grilling of all these Mafiosos. They were showing these interrogations in movie theatres, and selling tickets, and television sales went through the roof just based on those (Kefauver) hearings. Print the Legend is sort of about the book publishing industry, and the last book (Three Chords and the Truth) is the music industry.

Interviewer: I was particularly impressed with The Running Kind, where you have this meeting with Rod Serling who was one of the great television pioneers. It seemed to fit the story quite well. Something of an oddity in the series is Forever’s Just Pretend because of the absence of historical figures. It seems like in that novel you established a kind of plotting technique where you’d have Hector’s running battles with the cabal of local businessman and dubious law enforcement figures that is resolved about two-thirds of the way through, and the story kind of devolves into this series of quite bizarre confrontations with Miguel first and a chap called Mike. I was struck by the fact that they both have the same name anglicised. Was that something that you planned to have – a main plot and for the story to run out into a smaller plot and end on that point?

McDonald: I think that’s a fair point. I think that the book has some structural issues.

Interviewer: I quite like it like that!

McDonald: Another thing that Sallis did in the Lew Griffin novels: he insisted that time should be a protagonist, and occasionally some of the challenges I set for myself bent the narrative probably more in that book than in any other book. If you look at One True Sentence, that’s a week. The book is broken into sections by days of the week. In Print the Legend, I jumped decades. It starts in 57’. It makes a leap to 1967, and then it makes another leap to 1970. Toros & Torsos was set across several decades, several continents. And with Forever’s Just Pretend, I wanted to step away from this Zelig-like Woody Allen cameos by famous people because I just wanted to make it clear I could take the series away from that sense. There’s another writer named Max Allan Collins who writes a series about a private eye called Nate Heller, and his series uses a lot of historical characters and crimes, and I read those and I enjoyed them in the early going, but at some point I felt that this guy was attached to every crime on earth, knew every famous person and celebrity and I wanted to step away from that. The structure of Forever’s Just Pretend: it’s a love story. It’s supposed to resolve some of the loose ends of One True Sentence. One True Sentence and Forever’s Just Pretend are Hector Lassiter’s origins story becoming the writer he will become, and the man, the cheerfully vituperative cynic he appears to be later in the series. In that particular book, if you look at that structure, it moves across holiday weekends across the space of a year. I think it opens on Valentine’s Day, moves through Independence Day, Labor Day. I was trying to combine two real crimes in that book. At least in my head there was more linkage than maybe comes through in the final product. There was a series of crimes about that same time that occurred in Toledo, Ohio, where somebody was going round beating people to death with a baseball bat. It’s known as the Toledo Slugger killings, and at the same time there were a number of mysterious arsons across the Key West. So I left those crimes in place, and I took the Ohio baseball bat crimes and moved them to Key West.

McDonald: Another thing that Sallis did in the Lew Griffin novels: he insisted that time should be a protagonist, and occasionally some of the challenges I set for myself bent the narrative probably more in that book than in any other book. If you look at One True Sentence, that’s a week. The book is broken into sections by days of the week. In Print the Legend, I jumped decades. It starts in 57’. It makes a leap to 1967, and then it makes another leap to 1970. Toros & Torsos was set across several decades, several continents. And with Forever’s Just Pretend, I wanted to step away from this Zelig-like Woody Allen cameos by famous people because I just wanted to make it clear I could take the series away from that sense. There’s another writer named Max Allan Collins who writes a series about a private eye called Nate Heller, and his series uses a lot of historical characters and crimes, and I read those and I enjoyed them in the early going, but at some point I felt that this guy was attached to every crime on earth, knew every famous person and celebrity and I wanted to step away from that. The structure of Forever’s Just Pretend: it’s a love story. It’s supposed to resolve some of the loose ends of One True Sentence. One True Sentence and Forever’s Just Pretend are Hector Lassiter’s origins story becoming the writer he will become, and the man, the cheerfully vituperative cynic he appears to be later in the series. In that particular book, if you look at that structure, it moves across holiday weekends across the space of a year. I think it opens on Valentine’s Day, moves through Independence Day, Labor Day. I was trying to combine two real crimes in that book. At least in my head there was more linkage than maybe comes through in the final product. There was a series of crimes about that same time that occurred in Toledo, Ohio, where somebody was going round beating people to death with a baseball bat. It’s known as the Toledo Slugger killings, and at the same time there were a number of mysterious arsons across the Key West. So I left those crimes in place, and I took the Ohio baseball bat crimes and moved them to Key West.

Interviewer: I read Forever’s Just Pretend, and the death of Brinke, it did remind me of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service: the end scene. Then, when I read Death in the Face, Fleming specifically said to Hector, ‘I’m sorry I stole your tragedy’. I have read the novel On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, but quite a long time ago, and I’ve seen the film no end of times. What struck me about that film, it reminded me of your novel, when Blofeld and Irma Bunt drive past and machine gun the car. Bond jumps in the car and he’s like, ‘It’s Blofeld, let’s get him’, and we think we’re in for a good Bond-style chase here, but then he turns around and oh, now we’re not in a Bond film. Someone’s actually got hurt, and that reminded me of Hector. Shoot the bad guy, turn round and oh, there’s actually real tragedy here. Was that something you were going for?

McDonald: Yeah, and actually that was written as an homage to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I’m a tremendous Ian Fleming fan, and probably more than any other writer he’s been my biggest influence. I’ve probably read him, and reread, and reread him, more than any other author. The Lassiter series, if you really reduce it to its base component: it’s a single man who is a world traveller and an adventurer. He dresses well. He lives a pretty good life. He’s fond of alcohol. In reality, James Bond was a civil servant whose salary would never have supported that lifestyle. Even with some talented skills in gambling, it still would have been out of reach. I did have the Bond character in mind with Hector on a number of levels and Bond, he was nearly married twice. Vesper Lynd: I always think in Casino Royale, he was heading down that road with. I always admired the fact in Fleming that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service really calls back to Casino Royale. He meets these two women who he thinks of marriage with in the same place really. They’re similar characters in that they’re both in rough places in their lives, and in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, I felt Fleming turned a corner with that book. It’s probably my favourite of all of the Bond books, and I knew eventually I was going to have Ian Fleming in the series, so I was foreshadowing that. As you say, in Death in the Face, Fleming acknowledges that ‘Oh yes, I was thinking of you when I wrote that ending’. Tonally, I know that the film version of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service divides a lot of people, but I think it’s become more voguish to appreciate it now than at least it was. On my first viewing, I absolutely loved the film and Lazenby became my mind’s eye version of Bond, which I think is incredible as I really grew up with Sean Connery as Bond.

Interviewer: Yes, not to go too off topic, but I think he does a terrific job. I can’t imagine, as much as I admire Sean Connery, I can’t imagine him quite showing that vulnerability in some of the scenes where he’s being chased at the ice rink. He seems quite scared in an engaging way. Okay, Fleming only appears in one novel, but the two figures you come back to the most would be Orson Welles and Ernest Hemingway. You come at them at very different parts of their lives: the young idealistic Welles producing War of the Worlds is very different from the much more jaded, world-weary guy who’s got a second break directing Touch of Evil. Do you immerse yourself in scholarship? How do you approach these figures at different points of their lives?

McDonald: Well, I tended to plot these books to write from my passions, and through my teens Orson Welles was such a fixture on TV, particularly interview shows. He was always on (Johnny) Carson, Merv Griffin. He was making commercials, and he was a big bearded guy. So I didn’t really need to do a lot of research. I read a lot of biographies. I’ve read a ton of books about Welles and Hemingway, so it’s not like I need to go back and research them very much. I’m drawing from memory for the most part. Occasionally, with Welles particularly, I would watch YouTube interviews or drop in on some of his films to pick up the voice. But in my mind, I really wanted the series to look at the evolution of the artist Hector Lassiter, who ultimately proves to be really quite the survivor, and his three great friends are Orson Welles, Ian Fleming, Ernest Hemingway. All these people of young promise, charisma, and who ultimately created public images that they couldn’t support. I think literally all three of them were absolutely undone, if not even destroyed, by the personalities they shaped for themselves largely just to build their own celebrity. There is something poignant: in the original publication sequence you went from Print the Legend, which is the eulogy of Ernest Hemingway, back to One True Sentence where he is the young, charismatic war vet who’s about to create a new language or reinvent the American fictional language in print down to that really strong declarative form.

Interviewer: Well, speaking of writers and their personas, you talked of two of your inspirations, James Crumley and James Sallis, and an author who is quite important to me as well – James Ellroy. There’s delicious little details in there that Lassiter was comrades with Lee Ellroy on the Punitive Expedition. Can you describe some of the ways Ellroy, although his novels are very different, has inspired the series?

McDonald: I think it’s very clear, and in my very first reviews, I was having Ellroy’s name invoked a lot, starting with Head Games. In a way I was like Hector in that I was an English major and I was trying to write the American novel, and at some point in the late 80s, I picked up The Big Nowhere and I was absolutely enthralled by that book. In many ways it’s still my favourite of James Ellroy’s novels– his approach to writing about the 1940s in the way that he did. At the same time, I was reading the Max Allan Collins Nate Heller novels. I was reading a novel he had written set in the 1940s and that novel felt to me the most ‘curated’ in the museum sense, whereas Ellroy’s was so vibrant, and it seemed so contemporary and yet appropriately in its era. And I tried to do that with the Hector novels as well, not to have them be sort of embalmed with brand names. I read a lot of novels that are set in the thirties and forties, and I feel like I’m reading a novel that was written with a Sears Roebuck catalogue sitting next to it with the brand name of the moment. But I felt uncomfortable at various points with the whole Ellroy thing. Probably the most unusual moment was when we had completed Print the Legend, and it was to come out about the same time as Blood’s a Rover, and the book was locked down with my editor, and I got a copy of the galley of Blood’s a Rover and read that novel, and I was horrified to see that we were working on the some of the same territory. COINTELPRO comes up in both novels, and they both end with the death of J. Edgar Hoover at his home. Perhaps I see myself way too much in Ellroy’s stable anticipating where he was going with that book. I think Ellroy is just a landmark figure in crime fiction. Of all of the people who have come out in the last thirty of forty years, I think he’s probably done more to reinvigorate crime fiction, and it is so audacious what he has done. Because I am a Hemingway fanatic, I’m also incredibly engaged by Ellroy because he is such a stylist. Although, at times, that has obviously gotten him in trouble, as you know, following the style a little too far for some readers.

Interviewer: Yes, although I’m probably with Ellroy when he said of you, because you liked The Cold Six Thousand, that you’re among ‘the thirty per cent and the brave’. I really liked The Cold Six Thousand, and I liked it probably more than Blood’s a Rover, and I sometimes rue that the critical reaction sent Ellroy on a bit of a tangent. If we can move back to the metafictional issue, I’m quite intrigued by the question of authorship, it comes up in Forever’s Just Pretend. Hector is writing novels that bear the same titles as the novel you’re holding, but he’s also got ones like Rhapsody in Black, titles that are unique to him. Metafiction is by its nature vague… shifting. It’s quite dangerous territory. How did you navigate it?

McDonald: Yeah, I think that’s a tightrope you can fall off and some of those surrealistic touches I’ve had people say it’s knocked them out of the book a bit, and again, I was kind of winking toward James Sallis’ Lew Griffin series. That is another series where you find you have a detective/writer as a protagonist, and he is authoring novels that have titles that are the same as the novel you’re reading. So it does beg the question about the veracity of the narrator and the untrustworthy narrator, and Hector Lassiter is tagged with the slogan that he’s the ‘man who writes what he lives and lives what he writes’. I just always tried to write the books with the central notion that he is an author– that ultimately he is sharing the story with you even if he is not writing it down himself in the first person. In the early stories of his career he has fictional protagonists, and by the middle of his career he’s using himself as a protagonist in his own novels, so again it’s that drift from traditional narrative through Modernism toward something more experimental, and when he’s taken that as far as he can Hector more or less takes that persona out of the world and reinvents himself as a writer yet again.

Interviewer: Yeah, interestingly, in Print the Legend, Donovan Creedy: this kind of despicable Howard Hunt figure…

McDonald: Very much modelled on E. Howard Hunt yes.

Interviewer: […]Postmodernism, he says, is actually a conspiracy by the FBI to have all novelists write interminable intellectual waffle, which I thought was a very funny detail. We’ve talked a little bit about aesthetic movements being villains, and I do like the interchange between Hector and Werner Höttl in Roll the Credits. Höttl says: I made you. I created film noir. And the more I tortured you, the better you wrote. Even the title ‘Roll the Credits’ refers to attribution. Did you write that novel, because there’s many parallels between the two, with a view of Lassiter and Werner Höttl being kind of mirror images?

Interviewer: […]Postmodernism, he says, is actually a conspiracy by the FBI to have all novelists write interminable intellectual waffle, which I thought was a very funny detail. We’ve talked a little bit about aesthetic movements being villains, and I do like the interchange between Hector and Werner Höttl in Roll the Credits. Höttl says: I made you. I created film noir. And the more I tortured you, the better you wrote. Even the title ‘Roll the Credits’ refers to attribution. Did you write that novel, because there’s many parallels between the two, with a view of Lassiter and Werner Höttl being kind of mirror images?

McDonald: With Höttl being a mirror image to Hector?

Interviewer: Yeah, I know one’s a despicable character and ones the hero, but it seems like there’s so many parallels between them being father figures, being artistes.

McDonald: Oh yeah, absolutely. Whereas Hector is a little more benign in using his life as fuel for his fiction, in a lot of ways Höttl is Hector raised to the tenth level in that he’s aggressively doing that, and he’s willing to burn down the world for art essentially. He has these great visions and frustrations that he wasn’t able to create this film of the destruction of Paris that he hoped to achieve. They were very much meant to be flip side versions of one another.

Here’s the recently released cover image of Three Chords and the Truth.

An Ellrovian Journey

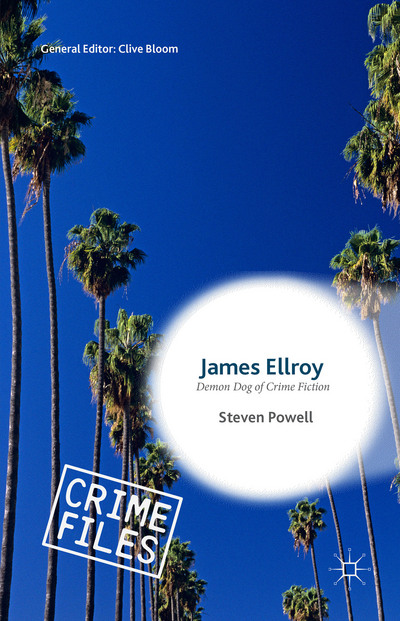

I have a piece in The Rap Sheet in which I discuss my new book on James Ellroy and my lifelong interest in the author. Here’s a taste:

It was a blurred image of the Kennedy motorcade which first brought my attention to the work of James Ellroy. I was in my mid-teens, on holiday with my parents on the south coast of England, when a leisurely detour through a local bookshop led me to spot a striking book cover that looked like it had been adapted from the Zapruder film: it was James Ellroy’s novel American Tabloid. I had never read Ellroy before, but a novel about the Kennedy assassination seemed interesting. Sure enough, a few pages in and I was gripped. Ellroy portrayed the assassination conspiracy from an Underworld perspective. His characters were brutal but sympathetic, the prose seemed both telegraphic and poetic. But what stood out more than anything else was Ellroy’s unapologetic determination to make the reader empathise with the characters who ultimately conspire to kill Kennedy. As he put it in the prologue, ‘America was never innocent. We popped our cherry on the boat over and looked back with no regrets.’

Of course back then I had no idea that I would one day write a book about Ellroy, but it was that chance discovery in a bookshop that was the genesis of what I like to call my ‘Ellrovian Journey’, a journey that culminated in the release last September of James Ellroy: Demon Dog of Crime Fiction, the latest addition in Palgrave Macmillan’s Crime Files series. Previous entries have included Barry Forshaw’s Death in a Cold Climate (2012) and Lee Horsley’s The Noir Thriller (2001). With this study of Ellroy, I have considered all of Ellroy’s major works, examining how his writing style has changed between novels. I have also analysed the role Ellroy’s Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction persona has played in his literary career.

You can read the full piece here.

The Elusive Film Adaptation of White Jazz

All I have is the will to remember. Time revoked/fever dreams – I wake up reaching, afraid I’ll forget. Pictures keep the woman young.

I knew my book was movie-adaptation-proof. The motherfucker was uncompressible, uncontainable, and unequivocally bereft of sympathetic characters. it was unsavoury, unapologetically dark, untameable, and altogether untranslateable to the screen.

Mulholland Falls is a tough and competent noir thriller. Set in early 1950s LA, Nick Nolte plays the leader of the ‘Hat Squad’, a four man LAPD detective team who use rough justice to deter organised crime figures from gaining a foothold in the City of Angels. If this seems vaguely familiar to Ellroy readers, then be aware there are many more similarities between the film and his writing (which I won’t go into here). But if anyone wants a thorough breakdown of how Ellroy’s work has been shamelessly plundered for the screen, do follow this Reddit thread on the similarities between the second season of True Detective and The Big Nowhere (1998). Nolte’s assistant on Mulholland Falls was the future film producer Greg Shapiro. In this interview for the LA Times, Nolte cheerfully discusses how he and Shapiro ‘stole’ Ellroy material for Mulholland Falls:

Mulholland Falls is a tough and competent noir thriller. Set in early 1950s LA, Nick Nolte plays the leader of the ‘Hat Squad’, a four man LAPD detective team who use rough justice to deter organised crime figures from gaining a foothold in the City of Angels. If this seems vaguely familiar to Ellroy readers, then be aware there are many more similarities between the film and his writing (which I won’t go into here). But if anyone wants a thorough breakdown of how Ellroy’s work has been shamelessly plundered for the screen, do follow this Reddit thread on the similarities between the second season of True Detective and The Big Nowhere (1998). Nolte’s assistant on Mulholland Falls was the future film producer Greg Shapiro. In this interview for the LA Times, Nolte cheerfully discusses how he and Shapiro ‘stole’ Ellroy material for Mulholland Falls:“We got into Ellroy’s books,” he says. “But after a while we had stolen so much that I said, ‘Greg, call Ellroy.’ Ellroy answers the phone and says, ‘Dog, here.’ ‘Cause he calls himself Dog. Greg explained who he was and what we were doing. Ellroy said, ‘Well, what are you taking?’ Greg had the quotes down. This line and this line.“And I said, ‘Give me the phone. James, it’s Nick Nolte. Here’s what we’ve taken so far. I think we’re right at the edge of taking too much.’ Ellroy said, ‘Look, I’ll meet you at the Pacific Dining Car in three days at eight o’clock.'”

Ellroy never received a writing credit for Mulholland Falls and the film never garnered much critical attention, although Roger Ebert was one of a minority of critics who admired it. Even in its title it was unlucky, as it would be eclipsed a few years later by David Lynch’s critically lauded Mulholland Drive (try typing Mulholland into your search engine and see what the predictive text gives you). Nevertheless, the meeting of Ellroy, Shapiro and Nolte would prove productive. Shortly thereafter, the three men were in discussions to do a film adaptation of White Jazz, with Nolte in the role of Dave Klein. Nolte briefly appears with Ellroy in the documentary Feast of Death (2001). He can be seen walking into the Pacific Dining Car, while Ellroy is holding court with his contacts in the LAPD. We can assume it was during this period that Nolte and Ellroy were working on White Jazz, and reports from back then suggest the project was developing strongly. Acclaimed cinematographer Robert Richardson was due to make his directorial debut with the film. John Cusack and Uma Thurman joined the cast. In the production notes of The Rules of Attraction (2002), Shapiro’s bio confidently states that the film was finished! However, in reality, the project soon ran into difficulty. In the brief glimpse I saw of various drafts of the screenplay and correspondence about the film at the Ellroy archive in South Carolina, I could tell there was tension between Shapiro and Ellroy. Shapiro raised issues about the financing and stated that everyone would have to work for less money. Ellroy responded irritably by scribbling obscenities next to Shapiro’s name in the letters he received. In any event the film was not well-conceived; several drafts had a contemporary setting which was confusing and robbed the story of much of its texture. Although he had been keen to adapt his novel at first, Ellroy eventually left the project. But the film did not die with his departure. The screenwriting/directing siblings Joe and Matthew Carnahan began developing the script for Warner Independent Pictures with George Clooney set to star (Clooney as Dave Klein really?). Joe Carnahan said of the adapted screenplay, ‘It’s, to me, what that book always was – the point of departure from the Eisenhower ’50s to the psychedelic freakshow, Manson ’60s. It’s a total combination of the two with a heavy, heavy voice-over narration, this kind of classic noir.’ The Carnahan script was available on SimplyScripts for a while. After downloading and reading a copy, I have to hand it to the Carnahan’s, they really did capture the essence of the novel. Although neither Dudley Smith or Ed Exley appear in the script to avoid confusion with a separate film project (L.A. Confidential 2 which thankfully never saw the light of day), the Carnahan’s seemed to take inspiration from a scene in the novel where Klein is heavily drugged and awakes to find himself watching a snuff film in which he is the star. To his horror, Klein sees his intoxicated onscreen self commit a grisly murder. In this film within a novel, Klein uses technical screenwriting terms, ‘Cut to’ and ‘Zooming in’, to describe what his character is doing onscreen. In the Carnahan screenplay, all of the action is described by the first-person narration of Klein. Take the scene below where Klein murders the witness Sanderline Johnson by throwing him out the window of a hotel room:

Ellroy never received a writing credit for Mulholland Falls and the film never garnered much critical attention, although Roger Ebert was one of a minority of critics who admired it. Even in its title it was unlucky, as it would be eclipsed a few years later by David Lynch’s critically lauded Mulholland Drive (try typing Mulholland into your search engine and see what the predictive text gives you). Nevertheless, the meeting of Ellroy, Shapiro and Nolte would prove productive. Shortly thereafter, the three men were in discussions to do a film adaptation of White Jazz, with Nolte in the role of Dave Klein. Nolte briefly appears with Ellroy in the documentary Feast of Death (2001). He can be seen walking into the Pacific Dining Car, while Ellroy is holding court with his contacts in the LAPD. We can assume it was during this period that Nolte and Ellroy were working on White Jazz, and reports from back then suggest the project was developing strongly. Acclaimed cinematographer Robert Richardson was due to make his directorial debut with the film. John Cusack and Uma Thurman joined the cast. In the production notes of The Rules of Attraction (2002), Shapiro’s bio confidently states that the film was finished! However, in reality, the project soon ran into difficulty. In the brief glimpse I saw of various drafts of the screenplay and correspondence about the film at the Ellroy archive in South Carolina, I could tell there was tension between Shapiro and Ellroy. Shapiro raised issues about the financing and stated that everyone would have to work for less money. Ellroy responded irritably by scribbling obscenities next to Shapiro’s name in the letters he received. In any event the film was not well-conceived; several drafts had a contemporary setting which was confusing and robbed the story of much of its texture. Although he had been keen to adapt his novel at first, Ellroy eventually left the project. But the film did not die with his departure. The screenwriting/directing siblings Joe and Matthew Carnahan began developing the script for Warner Independent Pictures with George Clooney set to star (Clooney as Dave Klein really?). Joe Carnahan said of the adapted screenplay, ‘It’s, to me, what that book always was – the point of departure from the Eisenhower ’50s to the psychedelic freakshow, Manson ’60s. It’s a total combination of the two with a heavy, heavy voice-over narration, this kind of classic noir.’ The Carnahan script was available on SimplyScripts for a while. After downloading and reading a copy, I have to hand it to the Carnahan’s, they really did capture the essence of the novel. Although neither Dudley Smith or Ed Exley appear in the script to avoid confusion with a separate film project (L.A. Confidential 2 which thankfully never saw the light of day), the Carnahan’s seemed to take inspiration from a scene in the novel where Klein is heavily drugged and awakes to find himself watching a snuff film in which he is the star. To his horror, Klein sees his intoxicated onscreen self commit a grisly murder. In this film within a novel, Klein uses technical screenwriting terms, ‘Cut to’ and ‘Zooming in’, to describe what his character is doing onscreen. In the Carnahan screenplay, all of the action is described by the first-person narration of Klein. Take the scene below where Klein murders the witness Sanderline Johnson by throwing him out the window of a hotel room:Drop the phone on the cradle…step to the

window…open it…then I chuckle genuine:ME:

Sanderline, you gotta see this…Trusting puppy Sanderline steps to the window:SANDERLINE JOHNSON:

What’m I--smash his head against the frame using his forward motion.

He loses muscle control for the split-second it takes me to

pitch his legs up and out. My face a quick-change evil mask.

Feature Sanderline’s nine-story fall. That Ambassador Hotel

robe billows behind him like a cape. He detonates an overhead

streetlight with a bomb sound, then hits the driveway.

Unzip my fly, hustle into the bathroom, screams from outside

now. Flush the toilet as Junior and Ruiz pile through the

door. Step out, play it baffled: look at the bed where

Sanderline sat, then the open window, screams floating up…ME:

DID THAT MUTT JUST JUMP?Lunge to the window: Sanderline post-mortem. Head shattered.

Valets sprinting.

Hawthorne in Bebington (and Prioleau in Liverpool)

My wife and I recently moved to Bebington. It’s a wonderfully peaceful area and, as a bookworm, I enjoyed making this discovery while walking past the nearby Mayer Hall.

This commemorative plaque describes Nathaniel Hawthorne’s visit to Bebington while serving as US Consul in Liverpool, when the city was vital to trading routes throughout the British Empire (apologies for the obstructive pole, there is building work currently going on at Mayer Hall).

Here’s the full text of Hawthorne’s journal entry ‘A Walk to Bebbington’, reproduced on the plaque:

Rock Ferry, August 29th.–Yesterday we all took a walk into the country. It was a fine afternoon, with clouds, of course, in different parts of the sky, but a clear atmosphere, bright sunshine, and altogether a Septembrish feeling. The ramble was very pleasant, along the hedge-lined roads in which there were flowers blooming, and the varnished holly, certainly one of the most beautiful shrubs in the world, so far as foliage goes. We saw one cottage which I suppose was several hundred years old. It was of stone, filled into a wooden frame, the black-oak of which was visible like an external skeleton; it had a thatched roof, and was whitewashed. We passed through a village,–higher Bebbington, I believe,–with narrow streets and mean houses all of brick or stone, and not standing wide apart from each other as in American country villages, but conjoined. There was an immense almshouse in the midst; at least, I took it to be so. In the centre of the village, too, we saw a moderate-sized brick house, built in imitation of a castle with a tower and turret, in which an upper and an under row of small cannon were mounted,–now green with moss. There were also battlements along the roof of the house, which looked as if it might have been built eighty or a hundred years ago. In the centre of it there was the dial of a clock, but the inner machinery had been removed, and the hands, hanging listlessly, moved to and fro in the wind. It was quite a novel symbol of decay and neglect. On the wall, close to the street, there were certain eccentric inscriptions cut into slabs of stone, but I could make no sense of them. At the end of the house opposite the turret, we peeped through the bars of an iron gate and beheld a little paved court-yard, and at the farther side of it a small piazza, beneath which seemed to stand the figure of a man. He appeared well advanced in years, and was dressed in a blue coat and buff breeches, with a white or straw hat on his head. Behold, too, in a kennel beside the porch, a large dog sitting on his hind legs, chained! Also, close beside the gateway, another man, seated in a kind of arbor! All these were wooden images; and the whole castellated, small, village-dwelling, with the inscriptions and the queer statuary, was probably the whim of some half-crazy person, who has now, no doubt, been long asleep in Bebbington churchyard.

The bell of the old church was ringing as we went along, and many respectable-looking people and cleanly dressed children were moving towards the sound. Soon we reached the church, and I have seen nothing yet in England that so completely answered my idea of what such a thing was, as this old village church of Bebbington.

The cottage Hawthorne refers to is Willow Cottage, and it is still every bit as beautiful and unique today as it was in Hawthorne’s time:

Oddly enough, this is not the first time I have accidentally stumbled across America’s ties to Liverpool and the surrounding area dating back to the Victorian era. In July of last year we held the ‘James Ellroy: Visions of Noir’ conference at the magnificent School of the Arts library at 19 Abercromby Square. It is now home to the University of Liverpool’s Department of English, but I didn’t realise until after the conference that in the nineteenth century it was the home of the Confederate financier Charles Kuhn Prioleau.

Hawthorne and Prioleau were on ideologically opposing sides of the American Civil War and, in many ways, the conflict would prove the undoing of both of them. Hawthorne had been recalled to the US before the outbreak of hostilities. He was ostracised in his native Massachusetts after writing the satirical piece ‘Chiefly About War Matters’ which was critical of the Union. Prioleau was one of the biggest Confederate supporters in Britain; his ‘contribution to the Confederate cause grew to sending supplies, weapons, and ammunition to those states, and finally to buying, equipping and crewing warships.’ Some of his actions at least had a humanitarian basis, as a recent article on the US Life and Limb exhibition stated Prioleau arranged ‘a five day grand bazaar at St George’s Hall to raise funds for the relief of wounded and imprisoned Confederate soldiers.’ However, Prioleau’s unflinching dedication to the Confederate cause eventually led to his bankruptcy, and some sources state he simply disappeared after the war, although this appears to be a simplification. His grave was discovered at Kensall Green Cemetary, London in the mid-1980s.

During the Ellroy conference, I was struck by how the beautiful Georgian architecture of 19 Abercromby Square reminded me of my visit to the James Ellroy archive at University of South Carolina. The USC campus in Columbia displays many architectural styles from building to building and is Heaven for anyone with even a passing interest in architecture. The connection it seems is not a coincidence. Prioleau had incorporated many architectural features into his Liverpool home that were common in his native South Carolina.

2015: Blogging Year in Review

For me, in blogging terms, 2015 has been the year of the two James’s. I refer of course to the world’s greatest fictional secret agent and the Demon Dog of American crime fiction.

Firstly, let’s talk about Bond. I am a massive fan of all things 007 related, but at the beginning of this year I hadn’t actually watched a Bond film since Skyfall was released. Perhaps it was my lukewarm feelings towards the film that put my interest in the series on hold. However, last Christmas my family bought me the DVD boxset, and I re-watched the entire series in order. It was a delight to relive all of the magic of Bond. I genuinely believe there has not been a flat-out stinker in the 24 official Bond films, although Die Another Day comes pretty close (if I’m feeling generous, the first hour of Pierce Brosnan’s swansong is fairly good). So just as the Bond films were beginning to re-enter my consciousness, the hype for Spectre was gaining momentum. Part of that hype is the ongoing debate online about who is the best Bond. Daniel Craig surely has a good claim to that crown, but Roger Moore was always my favourite. I began the year doing some research into the making of Octopussy. It’s not well remembered by either fans or critics, but it has two great distinctions: first, it beat Never Say Never Again in the infamous Battle of the Bonds, and second, it was the only Bond film co-written by George MacDonald Fraser of Flashman fame. He gave the film an exotic, colonial feel which later films in the series (dealing with audiences now accustomed to international travel) have abandoned. It was a great honour to see Sir Roger Moore at the Liverpool Empire Theatre in October. Moore is a natural raconteur and when he was discussing his favourite performance (or should I say two performances) in The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) it reminded me that his finest work onscreen was not as Bond, but his role in keeping the British film industry alive in the 1970’s with the help of some plucky, buccaneering producers.

Firstly, let’s talk about Bond. I am a massive fan of all things 007 related, but at the beginning of this year I hadn’t actually watched a Bond film since Skyfall was released. Perhaps it was my lukewarm feelings towards the film that put my interest in the series on hold. However, last Christmas my family bought me the DVD boxset, and I re-watched the entire series in order. It was a delight to relive all of the magic of Bond. I genuinely believe there has not been a flat-out stinker in the 24 official Bond films, although Die Another Day comes pretty close (if I’m feeling generous, the first hour of Pierce Brosnan’s swansong is fairly good). So just as the Bond films were beginning to re-enter my consciousness, the hype for Spectre was gaining momentum. Part of that hype is the ongoing debate online about who is the best Bond. Daniel Craig surely has a good claim to that crown, but Roger Moore was always my favourite. I began the year doing some research into the making of Octopussy. It’s not well remembered by either fans or critics, but it has two great distinctions: first, it beat Never Say Never Again in the infamous Battle of the Bonds, and second, it was the only Bond film co-written by George MacDonald Fraser of Flashman fame. He gave the film an exotic, colonial feel which later films in the series (dealing with audiences now accustomed to international travel) have abandoned. It was a great honour to see Sir Roger Moore at the Liverpool Empire Theatre in October. Moore is a natural raconteur and when he was discussing his favourite performance (or should I say two performances) in The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970) it reminded me that his finest work onscreen was not as Bond, but his role in keeping the British film industry alive in the 1970’s with the help of some plucky, buccaneering producers. My interest in Bond is as a fan, but my work on James Ellroy is as a scholar (but I hasten to add it’s no less pleasurable to me ). Perfidia was released late last year and the initial reviews, like Spectre’s, were mixed. Incidentally, Ellroy is not a Bond fan, but he did like Skyfall. I was deeply impressed by the novel and after completing my second reading this year I’m still dazzled by its breathtaking ambition and scope, particularly in how it relates to the original LA Quartet. However, it is flawed. Briefly put: occasional lapses into cartoon-like characterisation and one out-there plot twist concerning Dudley Smith somewhat marred the narrative. Still, Ellroy’s got three more novels in the series to put it right. There was plenty of talk about Perfidia, and all of Ellroy’s work, at the ‘James Ellroy: Visions of Noir’ conference which we held at the University of Liverpool this year. This was the first conference of its kind to be wholly devoted to the work of James Ellroy, and it was a great pleasure to meet both established Ellroy critics and postgraduate students who are writing their thesis on the Demon Dog. Then, in September, my new book James Ellroy: Demon Dog of Crime Fiction was published by Palgrave Macmillan. Why not treat yourself or someone special to a copy this Christmas. You can read an extract here.

My interest in Bond is as a fan, but my work on James Ellroy is as a scholar (but I hasten to add it’s no less pleasurable to me ). Perfidia was released late last year and the initial reviews, like Spectre’s, were mixed. Incidentally, Ellroy is not a Bond fan, but he did like Skyfall. I was deeply impressed by the novel and after completing my second reading this year I’m still dazzled by its breathtaking ambition and scope, particularly in how it relates to the original LA Quartet. However, it is flawed. Briefly put: occasional lapses into cartoon-like characterisation and one out-there plot twist concerning Dudley Smith somewhat marred the narrative. Still, Ellroy’s got three more novels in the series to put it right. There was plenty of talk about Perfidia, and all of Ellroy’s work, at the ‘James Ellroy: Visions of Noir’ conference which we held at the University of Liverpool this year. This was the first conference of its kind to be wholly devoted to the work of James Ellroy, and it was a great pleasure to meet both established Ellroy critics and postgraduate students who are writing their thesis on the Demon Dog. Then, in September, my new book James Ellroy: Demon Dog of Crime Fiction was published by Palgrave Macmillan. Why not treat yourself or someone special to a copy this Christmas. You can read an extract here.

So Bond and Ellroy have been my twin blogging obsessions of 2015. I plan to blog a bit more about both, and many more genre-related topics in 2016. Thank you to everyone who visited the blog this year. Happy holidays, and I hope you find yourself wandering onto this domain next year.

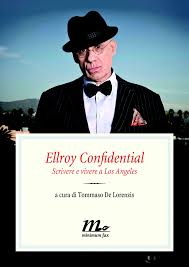

Ellroy Confidential

Ellroy Confidential is a new release of Ellroy’s interviews translated into Italian. Skilfully edited by Tommaso De Lorenzis, the book is in part an Italian version of Conversations with James Ellroy (2012). It features fifteen interviews that appeared in Conversations, conducted by such figures as Duane Tucker, Don Swaim and Craig McDonald. There are also two Ellroy interviews reprinted that I conducted myself: ‘Engaging the Horror’ and ‘The Romantic’s Code’. In addition, there is a recent interview Ellroy gave for Chris Harvey in which he discusses Perfidia. Ellroy Confidential is an impressive work, and I strongly recommend it to any Italian readers. It’s fascinating to see Ellroy’s hypnotic, rhythmical speech patterns in another language.

Ellroy Confidential is a new release of Ellroy’s interviews translated into Italian. Skilfully edited by Tommaso De Lorenzis, the book is in part an Italian version of Conversations with James Ellroy (2012). It features fifteen interviews that appeared in Conversations, conducted by such figures as Duane Tucker, Don Swaim and Craig McDonald. There are also two Ellroy interviews reprinted that I conducted myself: ‘Engaging the Horror’ and ‘The Romantic’s Code’. In addition, there is a recent interview Ellroy gave for Chris Harvey in which he discusses Perfidia. Ellroy Confidential is an impressive work, and I strongly recommend it to any Italian readers. It’s fascinating to see Ellroy’s hypnotic, rhythmical speech patterns in another language.

However, if you don’t speak Italian, treat yourself or someone special this Christmas to Conversations with James Ellroy.

British Politics Review – The Corbyn Gamble

The latest issue of the British Politics Review examines the future (presuming it has one) of the Labour party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. I have a written a piece titled ‘Jeremy Corbyn, the Spy Genre and a Cold War Prophecy’ which looks at how Labour’s lurch to the left was prophesied in such works as High Treason (1951), A Very British Coup (1982), and The Fourth Protocol (1984). Here’s a taste:

The latest issue of the British Politics Review examines the future (presuming it has one) of the Labour party under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. I have a written a piece titled ‘Jeremy Corbyn, the Spy Genre and a Cold War Prophecy’ which looks at how Labour’s lurch to the left was prophesied in such works as High Treason (1951), A Very British Coup (1982), and The Fourth Protocol (1984). Here’s a taste:

In Roy Boulting’s film High Treason, a group of British radicals plan to sabotage the country’s main power stations, crippling the economy as a precursor to installing a far-left government at Westminster. The plotters of High Treason belong to the respectable skilled working and middle classes, and are deeply embedded in British society, albeit with just enough deluded pomposity to stand out. The social historian Dominic Sandbrook describes the cast of fifth columnists as ‘a pacifist, a cat-loving and therefore clearly homosexual bachelor, two admirers of avant-garde music’ and the most contemptible of all, their leader ‘a well-bred Labour MP with a taste for rare vases’ (p.217). Boulting, a lifelong Liberal, clearly thought British communists were somewhat laughable. And yet, it is from precisely this far-left base that Jeremy Corbyn needs to build an agenda that will have national appeal. Labour have taken a massive gamble on Corbyn, hoping that a significant change in political consensus and a clear differentiation between them and the Tories will be enough to bring them back to power, but it is at the risk, as Tony Blair warned them of ‘annihilation’. High Treason was released in 1951 at a time when fear of communist subversion was a recurring cultural theme, and in succeeding decades, several works prophesied a subversive infiltration of Parliament. The novels A Very British Coup and The Fourth Protocol portrayed a fictional far-left takeover of the Labour Party. The irony is that with the election of Jeremy Corbyn this cultural prophecy has come true over twenty years after the end of the Cold War, and only eight years after Blair, Labour’s most successful leader and moderniser, stood down.

You can read the full issue here.

If you are not familiar with the British Politics Review, then I would heartily recommend it. The brainchild of Norwegian academics who are devoted to the study of British politics, it features political commentary far better than what you find in most broadsheets. In fact back in 2007, when he was still an obscure backbencher unlikely to ever become a parliamentary private secretary let alone leader of the Labour party, Corbyn himself wrote for the BPR:

Prime ministers effectively control Parliament through a system of patronage, where they reward loyal supporters with ministerial office. This influences the behavior of Members of Parliament, and is designed to buy loyalty. Having been a Member of Parliament since 1983 I have observed the way in which patronage operates, and the way in which Parliament can, on some occasions, do the opposite of what the public wants, out of loyalty to a prime minister rather than to a set of beliefs.

One can only hope that if Corbyn is serious about becoming PM he will remember these words. Although judging by his appointment of John McDonnell and Seamus Milne, I rather doubt it.

You can view previous issues of the BPR here.

‘

On the Trail of James Ellroy

I have written a piece for Martin Edwards blog about my new book on James Ellroy. Here’s a sample:

James Ellroy: Demon Dog of Crime Fiction began life as my thesis at the University of Liverpool. After I graduated, Palgrave Macmillan accepted my proposal for a new monograph on Ellroy, and I began to adapt my years of research on Ellroy into book form. There were two elements of James Ellroy’s career that I found particularly fascinating. One is referenced in the title of my study: his self-styled ‘Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction’ persona. I was determined to find out the full extent that Ellroy’s literary persona had played in shaping his works. Was it a major factor in his writing or did Ellroy simply call himself the Demon Dog to give a name to his often unhinged performances at book readings and during interviews?

You can read the entire piece here. Many thanks to Martin for giving me the chance to talk about the book.

Spectre: Sceptic or Believer?

On the debit side, the one member of the cast who was truly wasted was not Monica Belluci (she handles her small but important role well) but Stephanie Sigman. Sigman plays Estrella in the pre-credits sequence set during the Day of the Dead in Mexico City, and while its a thrilling scene, we do not see nearly enough of her for it to make sense casting a recognisable actress in the role. Another gripe was the design of the new headquarters of British Intelligence. It looks cool, evoking both the Shard and Gherkin, and the spiral structure is fittingly symbolic, but, really, was glass architecture the best choice? The whole point of a secret service is that people shouldn’t be able to see in, plus the last HQ was destroyed in a bomb attack so, I repeat, did they think through the glass design?

On the debit side, the one member of the cast who was truly wasted was not Monica Belluci (she handles her small but important role well) but Stephanie Sigman. Sigman plays Estrella in the pre-credits sequence set during the Day of the Dead in Mexico City, and while its a thrilling scene, we do not see nearly enough of her for it to make sense casting a recognisable actress in the role. Another gripe was the design of the new headquarters of British Intelligence. It looks cool, evoking both the Shard and Gherkin, and the spiral structure is fittingly symbolic, but, really, was glass architecture the best choice? The whole point of a secret service is that people shouldn’t be able to see in, plus the last HQ was destroyed in a bomb attack so, I repeat, did they think through the glass design?Spectre Review: The Dead are Alive

Yesterday my wife and I went to see Spectre. I hadn’t read any of the reviews and avoided the pre-release hype as much as possible so that my initial judgment of the film would not be coloured by anyone else’s opinion. My first reaction was that I liked it. I enjoyed the film a lot and think it ranks as one of the strongest entries in the series. And yet I also had the feeling that a significant minority of fans are not going to like it, but more on that later.

Yesterday my wife and I went to see Spectre. I hadn’t read any of the reviews and avoided the pre-release hype as much as possible so that my initial judgment of the film would not be coloured by anyone else’s opinion. My first reaction was that I liked it. I enjoyed the film a lot and think it ranks as one of the strongest entries in the series. And yet I also had the feeling that a significant minority of fans are not going to like it, but more on that later.

Spectre begins with the epigraph ‘the dead are alive’ hammered onto the screen with the brutal efficiency of an old typewriter. We are in Mexico City on the Day of the Dead. A five minute tracking shot follows Bond (attired in suitably ghoulish costume) through the streets as he hunts down Mafia Boss cum terrorist Marco Sciarra. He overhears Sciarra make a cryptic reference to ‘the Pale King’ before all hell breaks loose and the scene climaxes with Bond and Sciarra battling on board an out-of-control helicopter. Back in London, M is furious that Bond was in Mexico on an unsanctioned mission. Whitehall mandarin Max Denbigh ‘C’ is planning to abolish the licence to kill OO agents, so Bond has only a short time to uncover the organisation Sciarra and ‘the Pale King’ are working for. That’s about all I’ll say about the plot here. There is a deliberately loose narrative structure as director Sam Mendes keeps events moving from set pieces in Mexico, Rome, Austria, Morocco and London. But while the script is lacking in some regards (the reliance on four letter words to get cheap laughs is grating) there are still plenty of surprises and hardcore fans will enjoy the multitude of references to the previous films. More than that though, Mendes seems to be paying tribute to cinema as much as the Bond canon. The opening tracking shot is not just technically brilliant, it is playful, vibrant and alive with sinisterly sexy possibility. The helicopter battle seems anticlimactic by comparison, being over-reliant on CGI (but it never descends to the level of Die Another Day’s abysmal CGI effects). In fact none of the action sequences had any adrenaline pumping quality. I was won over by the film’s leisurely elegance, its beautiful use of colour and the abundance of surreal images such as Bond and Mr White’s daughter Madeleine Swann (a very strong Lea Seydoux) encounter with a spotless Rolls Royce in the middle of the African desert. The best action sequence I thought was a bone-crunching fistfight between Bond and the unstoppable killing machine Mr Hinx. All of the villains are well played in Spectre. Dave Bautista is memorable as Hinx (good at murder but lacking in polite conversation), Andrew Scott is wonderfully sleazy as C, Jesper Christensen once again steals the show as Mr White (I’ve become quite fond of the character now), and Christoph Waltz is just outstanding as the leader of the titular Spectre organisation. His near perfect mixture of malevolence and goofiness is a reminder that a Bond film is only as good as its main villain.

It all made for a great Bond film but an unusually subdued action film, which is why I think some of the younger fans who only really know Daniel Craig in the role won’t like it. Mendes seems to have reserved the London sequences for the younger fans. In these scenes all the lush romantic ambience of the film vanishes. In fact, Mendes noirish portrayal of London is so overcast in foggy gloom that if I worked for the London Tourist Board I’d consider suing. This for me was the one misstep, as things started to get reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s Batman films, but I appreciate different Bond fans take different things from the series. Daniel Craig has given the series a lot: Casino Royale seems to get better with every viewing, Quantum of Solace was a structural mess but still had some extraordinary scenes (the Vienna opera sequence is one of my favourite moments in cinema), Skyfall I thought was overrated, and Spectre wraps up all four films quite neatly. The resolution was so tidy that it dawned on me with sadness that this could be the last time Craig takes on the role. When the film ended, we sat through all the credits waiting for that reassuring message that ‘James Bond will Return’. When it finally came, its muted, split second appearance left me feeling despondent. I looked up to see a cleaner in a Halloween costume ready to usher us out of the screening (we were the last to leave). I know there are a lot of great actors out there who would be perfect as Bond, but Spectre was so good it made me want to see Craig in the role again. But if he doesn’t come back, then this film is a fine swansong.