Ice in the Blood: Women in Nordic Crime Fiction

I’ve been invited to speak on Women in Nordic Crime Fiction at the Nordic Church and Cultural Centre in Liverpool on May 30th. If you’re in Liverpool, and would like to visit this historical building (and eat some Scandinavian cake), please do come along (the event starts at 6 pm). I’ll be discussing depictions of women in Nordic crime fiction.

Two Theodora Keogh Novels Reissued

A few years ago I wrote a piece for The Rap Sheet on Theodora Keogh’s novel The Other Girl (1962) for their Book You Have to Read series, otherwise known as Forgotten Books. I only discovered Theodora Keogh and her writing after reading her obituary in the Telegraph. She had a remarkable life and career but in her later years her work had fallen into obscurity. The Other Girl is a disturbing, sometimes thrilling novel loosely based on the Black Dahlia murder case. I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys a good read, but especially to people interested in the Black Dahlia as it is an important and overlooked cultural depiction of the case. I’ve just learned from a fellow Theodora Keogh fan that Pharos editions, a Seattle based press, has just reissued Keogh’s novels The Tattooed Heart (1953) and My Name is Rose (1956) in a single volume featuring an introduction by Lidia Yuknavitch. Apparently, this is the first time these novels have been reissued since the 1970s, although Olympia Press did reissue Keogh’s other novels between 2002 and 2007.

I very much look forward to reading this volume, and I hope it leads to a wider revival of interest in Keogh’s work.

Thank You David Letterman

I was saddened to read that David Letterman has announced his retirement. Okay, he still has a year to go, and this announcement was not entirely unexpected but I, and I suspect many others, still felt a deep sense of loss. I remember a time when I was sitting in the pub with some friends discussing our favourite comedy shows. When I mentioned The Late Show with David Letterman everybody groaned. A lot of Brits just don’t get the exaggerated show-business style, the one-liners where you can see the punchline coming but laugh anyway, and the occasional outright silliness. Here in Britain we’ve become used to comedies being set on rundown council estates, mundane offices and inner-city parishes. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, and American audiences seemed to have lapped them up, but still, you can’t beat Letterman for sheer shameless, gleeful comedic entertainment.

I was saddened to read that David Letterman has announced his retirement. Okay, he still has a year to go, and this announcement was not entirely unexpected but I, and I suspect many others, still felt a deep sense of loss. I remember a time when I was sitting in the pub with some friends discussing our favourite comedy shows. When I mentioned The Late Show with David Letterman everybody groaned. A lot of Brits just don’t get the exaggerated show-business style, the one-liners where you can see the punchline coming but laugh anyway, and the occasional outright silliness. Here in Britain we’ve become used to comedies being set on rundown council estates, mundane offices and inner-city parishes. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, and American audiences seemed to have lapped them up, but still, you can’t beat Letterman for sheer shameless, gleeful comedic entertainment.

I remember when I was an undergrad and was living in a house with seven other students (which was a disaster but I’ll save that story for another time). No one wanted to watch Letterman at 11 so I had to stay up to 6am to catch it. It would always be worth it for his opening monologue, the Top Ten, the comic sketches, the rapport with Paul Shaffer and Alan Kalter. I was less fussed about who the guests were. Letterman was the star. Alas, I never became famous enough to be a guest on the Late Show, but I would have the opportunity to sit in the Ed Sullivan Theatre watching the show being recorded.

Last year I visited New York for the first time. I was there partly to retrace the steps of James Ellroy during a particularly interesting period of his literary career and partly just as a tourist. Walking through Broadway, my wife and I stumbled across the Ed Sullivan Theater with the large picture of Letterman outside it. ‘Let’s see if we can get tickets’ my better half suggested. My English cynicism kicked in. I knew tickets were free but were allocated on a lottery basis and competition must be fierce. Still we put our names down and were told to call back later in the day. As neither of our mobiles worked abroad we called back from a phone box (not easy to find these days), only to be told that we hadn’t been selected. Still, call back tomorrow they said just in case anyone dropped out. We called back the next day merely as a formality, but to our delight we were told we were in. Queuing up in the Ed Sullivan Theater, chatting to Australian tourists, I felt somewhat apprehensive. We had no idea who the guests were and I was terrified that Letterman would pick on me on national television. Regular viewers will know he often engages people in the audience and more than a few of them come across as foolish. The interns (some of whom were quite fetching, no wonder he strayed) briefed us before we took our seats. Letterman feeds off your energy, they said. If he feels the audience is not involved he may hold back some of the best material for another show. We want hearty laughter and enthusiastic applause, even if you don’t find everything funny, but no cheering as it’s a distraction. So, they took us to our seats, and I was taken aback by how small everything was. The stage looks a lot bigger on TV and there were times when I thought the cameraman was going to knock over someone in the band. Before filming began, the audience was fired up with some funny videos and a stand-up comic. Letterman came on to say a few words. This was the only time it felt like he was talking to the audience directly. When filming began he was looking into a camera that was right in front of him, which I assume is a lot less nerve-wracking than looking out at an auditorium of several hundred people. There were TV sets in the auditorium so we could see the show in the same way it was broadcast that very night. The show itself was a joy to watch. The monologue was very funny. The Edward Snowden scandal was in the news and there were lots of jokes about his ‘hot, pole-dancing girlfriend’. One sketch I thought that dragged was trimmed down a lot when it was shown on TV. The guests were Idris Elba and Melissa McCarthy, both of whom were charming, although the films they were plugging looked awful. During the commercial breaks we were treated to several thumping rock songs by the ever-excellent Paul Shaffer and the CBS Orchestra. The closing musical act was Dale Watson and the Lone Stars performing the wonderful ‘I Lie When I Drink’.

Leaving the Ed Sullivan Theater that day I felt completely invigorated and overjoyed. Thank you David Letterman.

Detroit: An American Autopsy by Charlie LeDuff

Before beginning my review of Charlie LeDuff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy (2013) it might be helpful to give a little personal background. My wife is from the Detroit suburbs. I first visited the city in 2006 and have been back many times. In spite of all its problems, I do love the city and am happy to call it home when I’m in the US. So, when my father-in-law bought me a copy of LeDuff’s bestselling, deeply personal view of Detroit, I was looking forward to reading it. Unfortunately, work commitments meant that I just didn’t have the time until just last week. After spending a night flashing the hash, I was rushed to hospital with abdominal pains and told that I needed my appendix removed. I read the book restricted to a hospital bed, doped up to my eyeballs, which you might argue is the perfect way to learn about Detroit.

Before beginning my review of Charlie LeDuff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy (2013) it might be helpful to give a little personal background. My wife is from the Detroit suburbs. I first visited the city in 2006 and have been back many times. In spite of all its problems, I do love the city and am happy to call it home when I’m in the US. So, when my father-in-law bought me a copy of LeDuff’s bestselling, deeply personal view of Detroit, I was looking forward to reading it. Unfortunately, work commitments meant that I just didn’t have the time until just last week. After spending a night flashing the hash, I was rushed to hospital with abdominal pains and told that I needed my appendix removed. I read the book restricted to a hospital bed, doped up to my eyeballs, which you might argue is the perfect way to learn about Detroit.

LeDuff is a Detroit native who, like many of his fellow Detroiters, left the city in search of a better life and career. He has enjoyed a distinguished career as a journalist, contributing to a Pulitzer prize winning New York Times series and winning the Meyer Berger award. However, after finding himself somewhat bored with the direction of his career, LeDuff began to feel an irresistible urge to write about his hometown. But the big newspapers were not interested:

No thanks, they told me. Detroit was nothing. Besides, the newspaper and magazine businesses were crumbling and the last thing any executive editor was willing to do was spend the money to open a boutique bureau in Dead City.

LeDuff finally secured a position at the Detroit News, a newspaper whose money problems mirrored those of the city itself. The offices were dimly lit and LeDuff had to get use to broken chairs, broken tables and computers that didn’t work. Given his rather uncomfortable working conditions, it is perhaps no surprise that LeDuff has written an unconventional and eccentric book. If you are looking for a scholarly, chronological history of Detroit, then this is not the book for you. LeDuff begins on the day he was covering a ghoulish story – the discovery of a corpse encased in ice at the bottom of an elevator shaft in an abandoned building – and then jumps back to the riots of 1967, charting the history of the city from the corrupt mayoralty of Coleman Young to the recent ultra-corrupt mayoralty of Kwame Kilpatrick. Like many Detroiters, LeDuff has personally suffered from the decline of the city. His sister fell in with a group of bikers and became a prostitute. She died in a car crash. LeDuff also writes candidly and movingly about one time when his marriage was on the rocks, and he came close to committing a serious act of domestic abuse. There are many sad and sickening stories in this book, but there is also a great deal of humour in the indignation:

I was going to find out who was responsible for the outrage of murderers walking free while the city burned night after night. I was going to become a real reporter. Someone had to answer for this shit. The dignified burial of Johnnie Dollar and the demolition of Harris’s death house gave me confidence. The people of Greater Detroit deserved better than to be robbed by their leaders and forgotten by their neighbors.

I threw my cigarette butt into the sewer grate. I looked up into the rain. That’s when a bird shit in my face.

The chapters on Mayor Kilpatrick and his venal, money-grubbing minion Monica Conyers are particularly good. For readers not familiar with Kilpatrick, he is probably one of the most corrupt politicians in American history and is currently serving twenty-eight years in prison. Although LeDuff is on shaky legal ground when he explores longstanding rumours that a stripper, Tamara Greene, was assaulted by Kilpatrick’s wife Carlita at the Manoogian Mansion party. Greene was later murdered in a drive-by shooting and some commentators suggested a political conspiracy. Far-fetched? Yes, but in Detroit anything’s possible. Still, there’s something rather pathetic about Kilpatrick and Conyers, which makes it impossible to view them as complete villains. LeDuff reproduces text messages between Kilpatrick and chief of staff and lover Christine Beatty which are just hilarious, as LeDuff puts it:

While lacking meter and polish, the fire and passion in their electronified love sonnets must surely rate with those of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning.

All in all, a fascinating and funny book. In an odd way, it made me look forward to going back to Detroit.

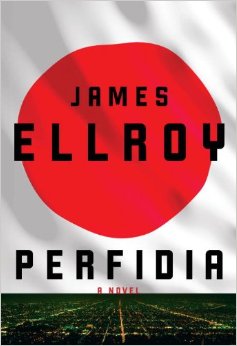

First Look at Perfidia Front Cover

Amazon.com is now displaying the front cover of James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia, and it’s quite striking. I expect a novel such as this will feature many different front covers over the years, but I thought I would say a few words about this one. The novel is set in Los Angeles, December 1941, during America’s entry into the Second World War. Ellroy has revealed that the notorious internment of over 100,000 citizens of Japanese heritage will be a major theme of the novel, although judging by this interview expect Ellroy’s portrayal to be controversial:

Amazon.com is now displaying the front cover of James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia, and it’s quite striking. I expect a novel such as this will feature many different front covers over the years, but I thought I would say a few words about this one. The novel is set in Los Angeles, December 1941, during America’s entry into the Second World War. Ellroy has revealed that the notorious internment of over 100,000 citizens of Japanese heritage will be a major theme of the novel, although judging by this interview expect Ellroy’s portrayal to be controversial:

Although the story is very much about the injustice of the internment of the Japanese – most of them innocent – let me say, and this is very un-PC, the f*cking internment was not the Holocaust or the Soviet Gulag.

The cover then is very symbolic. The Japanese flag looms in the air over the lights of the City of Angels by night. Pearl Harbor, of course, was an aerial attack therefore the elevated flag seems appropriate. Also, the flag hangs ominously suggesting the widespread paranoia following Pearl Harbor that there was a Japanese Fifth Column in the US. At first I thought the cover was somewhat misjudged considering Japanese-Americans are, to a certain degree, the victims of this period of LA history. Why should the flag tower above LA as though they were more powerful than the city? However, the flag on the cover is the Japanese national flag. If I am not mistaken, the more aggressive symbol of Japanese imperialism at the time was the flag of the Imperial Navy:

It may be over-reading, but perhaps by choosing the Japanese national flag the cover designer is demonstrating that this is a story about Japanese-Americans as people and not about the Empire of Japan and its colonial ambitions, for which the Imperial Navy flag may have been more appropriate as the sun’s rays suggest expansion whereas internment completely overestimated Imperial Japan’s infiltration of the US.

Anyway, this makes me hungry to read the book so its fairly good advertising.

Two Writers on Liverpool

I tend not to read much about my adopted home city of Liverpool as I see books as a form of escape. As much as I like Liverpool, I’d rather read about 1940s Los Angeles or nineteenth century India. However, I recently read two very different perspectives on Liverpool, both of which I’d recommend.

I tend not to read much about my adopted home city of Liverpool as I see books as a form of escape. As much as I like Liverpool, I’d rather read about 1940s Los Angeles or nineteenth century India. However, I recently read two very different perspectives on Liverpool, both of which I’d recommend.

Firstly, Michael Macilwee’s excellent true crime book The Gangs of Liverpool (2007) depicts gang violence in late Victorian Liverpool . I was pleased to notice some parallels between the author and myself. Dr Macilwee works for John Moores University Library, whereas I work for their friendly rival the Sydney Jones, and we also studied for the same Master’s degree, Victorian Literature, a degree which every librarian in Liverpool seems to have taken.

Macilwee begins with the Tithebarn Street Outrage of 1874 and chronicles gang violence in Liverpool throughout the late Victorian era. Crime and poverty were rife in the city, giving Liverpool a reputation as a dangerous place. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who served as American Consul in Liverpool from 1853-1857, complained that even a man of his position couldn’t afford to live in Liverpool, then a great commercial city, and yet was shocked at the poverty in places like Tithebarn Street:

I never saw … nor imagined … what squalor there is in the inhabitants of these streets as seen along the sidewalks. Women with young figures, but old and wrinkled countenances; young girls without any maiden neatness and trimness, barefooted with dirty legs. Women of all ages, even elderly, go along with great, bare, ugly feet, many have baskets and other burthens on their heads. All along the street, with their wares at the edge of the sidewalk and their own seats fairly in the carriageway, you see women with fruit to sell, or combs and cheap jewellery, or coarse crockery, or oysters, or the devil knows what, and sometimes the woman is sewing meanwhile.

Macilwee meticulously traces the crimes of the Cornermen and High Rip gang, and the sentences imposed on them by the judges they feared. The book is at its strongest when looking at the parallels between Victorian and contemporary attitudes to crime. Every generation, Macilwee argues, seems to think it is living in an age when crime is spiralling out of control. This entails viewing the past as relatively crime- free and regarding each new crime in the present as plumbing new depths of depravity. It is easy to look at the Scallies of today and think the next generation is growing up without values,but people thought the same thing when the Teddy Boys emerged in the 1950s. Indeed, Macilwee examines whether the High Rip gang, fierce and notorious by reputation, ever actually existed. Were the High Rippers a single criminal entity or the product of persistent rumour? Did the sensationalist press coverage fuel public fear by labelling every crime as the latest High Rip outrage?

After reading The Gangs of Liverpool, I came across a very different perspective of the city. A friend recommended Alan Bennett’s play Kafka’s Dick (1986). Having read the play (which is very funny and highly recommended by the way) I found the edition contained a short diary by Bennett of some time he spent in Liverpool in the mid -1980s during the production of a film on Kafka he had written. Bennett clearly doesn’t like the city, and he expresses some hilarious views of Liverpool and its inhabitants, which could ruin a political career if spoken by a Tory MP, but he seems to be able to get away with as a left-wing playwright. One description of the centre of the city caught my eye:

Behind the war memorial one looks across the Plateau to the Waterloo Monument and a perfect group of nineteenth-century buildings; the library; the Walker Art Library and the Court of Sessions. Turn a little further and the vista is ruined by the new TGWU building, which looks like a G-Plan chest of drawers. A blow from the Left. Look the other way and there’s a slap from the Right – the even more awful St John’s Centre. Capitalism and ideology combine to ruin a majestic city.

I think Bennett’s right to highlight the area around St George’s Hall as one of the most historical and beautiful parts of the city. As he was writing thirty years ago, you can see why he might not care for the TGWU building, as the city was in the grip of Militant. And as the country was in the grip of Thatcherism, he didn’t much care for St John’s Shopping Centre either. But times change. Today St John’s Centre comes across as an old-fashioned working class market. Most shoppers have been drawn away by the sleek, modern Liverpool One, and while there are still some big name stores in St John’s, its collection of tiny- family run barbershops and greasy spoon cafes seems like the perfect antidote to the consumerism Bennett detests.

I think Bennett’s right to highlight the area around St George’s Hall as one of the most historical and beautiful parts of the city. As he was writing thirty years ago, you can see why he might not care for the TGWU building, as the city was in the grip of Militant. And as the country was in the grip of Thatcherism, he didn’t much care for St John’s Shopping Centre either. But times change. Today St John’s Centre comes across as an old-fashioned working class market. Most shoppers have been drawn away by the sleek, modern Liverpool One, and while there are still some big name stores in St John’s, its collection of tiny- family run barbershops and greasy spoon cafes seems like the perfect antidote to the consumerism Bennett detests.

Anyway, these were both entertaining reads on the city. If you have any recommendations of books on Liverpool I should read, I would love to hear about them in the comment thread.

James Ellroy: A Companion to the Mystery Fiction

If you’re finding the wait for James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia to be unbearably long, then I would recommend the recently released James Ellroy: A Companion to the Mystery Fiction by Jim Mancall. Mancall has written articles about Ellroy before and clearly knows his stuff. The book is arranged as an encyclopedia so L is for L.A. Confidential etc., and is a delight to dip in and out of. I was gratified to see Mancall references Conversations with James Ellroy quite a bit, including a close look at the intriguing Duane Tucker question. What I am enjoying most about the book so far, however, is the short biographies of Ellroy’s minor and major characters. It’s interesting to read about Duane Rice and Lenny Sands and Ross Anderson as individuals and not just as characters in a larger narrative. The companion is both an authoritative and enjoyable read.

If you’re finding the wait for James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia to be unbearably long, then I would recommend the recently released James Ellroy: A Companion to the Mystery Fiction by Jim Mancall. Mancall has written articles about Ellroy before and clearly knows his stuff. The book is arranged as an encyclopedia so L is for L.A. Confidential etc., and is a delight to dip in and out of. I was gratified to see Mancall references Conversations with James Ellroy quite a bit, including a close look at the intriguing Duane Tucker question. What I am enjoying most about the book so far, however, is the short biographies of Ellroy’s minor and major characters. It’s interesting to read about Duane Rice and Lenny Sands and Ross Anderson as individuals and not just as characters in a larger narrative. The companion is both an authoritative and enjoyable read.

The Great War’s Culture War

The latest issue of the British Politics Review takes as its subject the First World War. A few months ago I contacted one of the BPR’s editors Øivind Bratberg as I had an idea for an article about humorous depictions of the conflict. I was intrigued by the idea that there were relatively few comedic portrayals of the First World War in comparison to the Second World War. However, the humorous portrayals that have been made (Oh! What a Lovely War, Blackadder etc.) seem to have had a profound effect on both public and academic thinking on the subject. Anyway, I began writing the article, and then Michael Gove and Tristram Hunt began a war of words in the newspapers about almost the exact same subject. This was something of a mixed blessing in terms of writing the article, but it brought home how important and contentious cultural depictions of the war can be.

This is my third article for the British Politics Review, you can read the previous two here and here, and is titled ‘The Great War’s Culture War’. Here’s the link to the whole issue.

James Ellroy: Faith of a Demon Dog

Religion is a topic that has popped up occasionally in James Ellroy’s work. I have always found his views on the subject to be intriguing, but I have been reluctant to blog about it. After all, a man’s faith is private, and Ellroy has come across as tetchy when quizzed on it by interviewers. I don’t blame him, there is a danger Ellroy’s critics would try and use his religious views as a stick to beat him with. However, I do believe Ellroy’s statements on faith and the sometimes allusive, sometimes direct references to it in his writing are worth examining.

Ellroy’s first encounter with religion was as a child in the early 1950s. When his parents divorced, his mother Jean sent him to a Dutch Lutheran Church every Sunday on his own. Naturally, Ellroy resented her for this. His mother was trying to discipline him, and she thought some knowledge of Christianity, however vague, would shape him morally, but there was a whiff of hypocrisy. She was drinking heavily and dating men (by the social conventions of the time she may have been labelled promiscuous) now that her marriage was over. During one argument, she struck Ellroy viciously. At this stage of his life, Ellroy hated his mother and probably thought little of religious faith as a consequence. After her murder, Ellroy began to take a different view. He was now living with his father Lee, a chronically lazy man who made little effort to discipline him. As his father’s health deteriorated, Ellroy’s behaviour began to spiral out of control. The death of Lee Ellroy in 1965 meant that the last vestiges of restraint had disappeared from Ellroy’s life. His existence descended into a nightmare of drug and alcohol abuse, petty crime and sexual voyeurism. Ellroy was arrested over a dozen times and did several short stints, ‘soft time’, in the LA County Jail. In later years, Ellroy would note the irony of his life compared to his mother. She was indulging her vices at a time when it was taboo, and it may have led to her murder. As an adult, his behaviour had been marked with even less restraint, but changing attitudes in 1960s and 1970s society allowed him to indulge himself more freely.

A series of health scares led Ellroy to become fully sober in 1977. It’s fair to say that in his years of excess living between 1965 and 1977, religion was not at the forefront of Ellroy’s mind. However, in his second memoir The Hilliker Curse (2010) Ellroy describes a moment during this period when he was physically weak and without a place to stay for the night, and he had a spiritual experience which he believes saved his life. I won’t quote it here as it is on the last page of the book, but it appears to be the closest Ellroy has come to a Damascene conversion. Another theory is that Ellroy’s years of addiction and criminality were a form of spiritual lapse that he knew he was going to pull himself out of one day. Ellroy described to interviewer Martin Kihn how during one stint in jail he thought ‘[he] should’ve been in grad school somewhere’. Perhaps it’s no surprise then that when he turned to writing after sobriety, his thoughts on religion were to emerge.

Ellroy’s first novel Brown’s Requiem was published in 1981. It contains an intriguing reference to God. When, seemingly by chance, the lead character, Fritz Brown, spots a young Mexican woman connected to the case he is investigating, Brown ponders this coincidence: ‘Walter used to tell me that everything in life was connected. I didn’t believe him. Now I did. It was eerie, almost like proof of the existence of God.’ I love this quote, but I think Ellroy is primarily making a comment here about the crime genre, in a mystery of this kind, everything connects and the author is omniscient, seeing everything. Brown’s comment feels conspicuous in the novel as the character is a staunch atheist.

This would not be the only time Ellroy would use religion as a comment on the genre. In an interview I conducted with Ellroy he made a reference to Christ, and it was clear that he saw God and religion as having aesthetic purposes, defining not just his own faith but also his role as an author and distinguishing his writing from other cultural forms:

In his famous quote when he [Beethoven] started to go deaf, “I will take fate by the throat.” It’s just almost unfathomable courage. And the older he got, and he was dead at fifty-six, the more unfathomable and great and uncategorizable his music. So this is largely what Christianity asks of a writer in a secular world. Will you ascend to Christ’s example? What Beethoven asks of you, will you ascend to my example? Who do you want to be? Do you want to be Beethoven or do you want to be Hunter S. Thompson? I mean, really, do you want to go out and abuse women and use drugs and squander your potential because it’s cool. It’s one of the reasons that I devoutly dislike rock ’n’ roll and the mindset of rock ’n’ roll, and the fact that there’s sixty-five- and seventy-year old rock ’n’ rollers out there in a state of perpetual reaction and perpetual rebelliousness. And I see it a lot in Britain. These aged ass rock ’n’ rollers. Holy shit! And you’re sentencing yourself to a life of the puerile. And I would rather, and I’m not in any way saying that I’m Jesus Christ or Beethoven, I would rather always ascend because I have that knowledge that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Of course Ellroy may have ascended as a writer but he also experienced the descent of crime and sin. The struggle between these two forces has formed the basis of some of his greatest characters, and the novel in which he addresses religion most directly is, I believe, Suicide Hill (1986). On the surface, the novel appears at first to have a strongly anti-religious undercurrent to the narrative. Of the genuinely religious characters, one is a psychotic and the other is an ambitious, ruthless policeman whose Evangelical group are attempting to take over the LAPD. Two brothers, Bobby and Joe Garcia, impersonate priests to solicit donations off elderly and vulnerable Catholics, and there is even a scene where a character walks into a pornography store where the desk clerk is reading the Jehovah’s Witness magazine, Watchtower. On the other hand, all of the characters are looking for redemption in whatever form they can find it. Bobby Garcia makes a confession to a Catholic priest shortly before he is murdered in church by fellow criminal, Duane Rice:

The poor box was on the side wall near the rear pews, ironclad, but too small to hold sixteen K in penance bucks. Bobby started shoving cash in the slot anyway, big fistfuls of c-notes and twenties. Bills slipped out of his hands as he worked, and he was wondering whether to leave the whole bag by the altar when he heard strained breathing behind him. Looking over his shoulder, he saw Duane Rice standing just outside the door. His high school yearbook prophecy crossed his mind: “Most likely not to survive,” and suddenly Duane-o looked more like a priest than the puto with the alligator fag shirt.

Bobby dropped the bag and fell to his knees; Rice screwed the silencer onto his .45 and walked over. He picked up the bag and placed the gun to the Sharkman’s temple; Bobby knew that defiant was the way to go splitsville. He got in a righteous giggle and “Duhn-duhn-duhn-duhn” before Rice blew his brains out.

Bobby is trying to atone for his sins by shoving stolen money into the poor box, but when he sees Duane, he realises only his death will fully pay for his sins. He faces his murderer with some bravery, but despite his new found righteousness there is part of his criminal life that seems to be pulling him back. He hums the the theme tune to Jaws before Duane shoots him, a reference to Bobby’s street name Sharkman which he acquired after a series of sexual assaults on young women.

Naturally Ellroy is a much better man than his ill-fated character Bobby Garcia, but the times he has come closest to Christian piety, he has always maintained a flicker of irreverence and playfulness similar to Bobby’s. In his essay ‘I’ve Got the Goods’ Ellroy describes how he was enjoying conversations about God with a Pastor in his then- home town of Kansas City, and he was interested in joining the Lutheran ministry.

My wife finds this calling dubious. She sees me as a man of soiled cloth. I wouldn’t hack divinity school. I’m too joyous and profane. I see God in foul language and sex. I’m more L.A. than Kansas City. The Lutheran Church would disdain me.

It’s not just the Lutheran Church that might find the Demon Dog a tad contentious for its taste. In his wonderful essay ‘Let’s Twist Again’ Ellroy writes of how he organised a High School reunion thirty-six years after he left John Burrough’s High. One of his former classmates, Howard Swancy, had become a pastor. In some respects, Swancy was not dissimilar to Ellroy. He had an interest in law enforcement but ‘flunked the screening process’ for the LAPD. He was also a dominant and charismatic performer who ‘liked to run the show’. Ellroy visited Swancy’s Peace Apostolic Church and makes it clear that what he heard of the exclusivist only Jesus saves theology, ‘restrictive housing law in Heaven’, was not for him. The essay ends with a touching moment when Ellroy spots a young boy in the congregation:

Howard cranked it out. I looked around the pews. I locked eyes with a tall black kid. He looked bored and agitated.

I winked. He smiled. The apostolic Church of Peace turned into the Peppermint Lounge.

I sent up a prayer for the kid. I wished him imagination and a stern will and lots of raucous laughs. I wished him a wild mix of people to breeze through and linger with over time.

It is as though Ellroy is seeing himself in the boy all those years ago in the Dutch Lutheran Church his mother made him attend. His discomfort in Swancy’s church may be just a clash of styles, as he doesn’t use it to argue atheism. Indeed, it is telling that he chose to visit. And yet, like the opposite of Chesterton’s ‘a twist upon the thread’ the most profound moment comes when he shares an empathetic look with a kid who is equally bored with Swancy’s fire-and-brimstone nonsense. As with Bobby Garcia’s death scene in Suicide Hill, the trace of the subversive drags him away from Christian piety.

Views change over time, of course, and it can be very difficult to truly know what another man thinks on a subject as big as God, especially as often we don’t know ourselves what we believe. As much as we might look at the aesthetic and subversive elements of Ellroy’s faith, it has become an increasingly direct and simple one. The subversion still remains, but any doubt seems to have evaporated. I once asked him whether he thought there was a presence of God in his writing, and his answer was as honest and direct as any interviewer could hope for:

Yeah I do. I do and I’m a Christian. I’m not an Evangelical Christian, but God and religious spiritual feelings always guided me during the worst moments of my life, and I don’t for a moment doubt it. […] And I always like getting in asides and putting it out there and stopping just short of preaching.

Mencken and Sara

I’ve been a fan of the dying art of letter writing ever since I read the wonderful A Friendship: The Letters of Dan Rowan and John D McDonald, so I was delighted to come across Mencken and Sara: A Life in Letters (1992) edited by Marion Elizabeth Rodgers. H.L. Mencken was the renowned journalist, magazine editor and acerbic critic of American society. Sara Haardt was a professor of English Literature and promising young author. Their correspondence began in 1923 and ended with Sara’s death twelve years later from tuberculosis aged only 37. Rodgers divides the letters into two sections, ‘The Courtship Years’ and ‘The Marriage Years’. The attraction between Mencken and Sara is evident from the start of the collection, and despite the ‘Sage of Baltimore’s’ well-known opposition to marriage, they wed in 1930.

Part of my reason for reading the book was that I thought I might learn a few things about a particularly rich period in American crime fiction writing. Mencken was the co-founder of Black Mask magazine in which authors such as Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett began their writing careers with short stories which defined the hardboiled style. However, on this point, I was disappointed. In his letters, Mencken talks at length about The American Mercury, the Monkey Scopes Trial, his disdain for President Coolidge and Romantic admiration for Imperial Germany, but he makes no mention at all of Black Mask and only one mention of his close friend and colleague James M. Cain, another creator of the hardboiled school. However, in her excellent seventy-page introduction to the book, Rodgers mentions Cain several times, and it is clear that, although he may not have intended to, Cain had a big impact on Mencken’s and Sara’s relationship. Mencken had been romantically linked with the famed silent movie actress Aileen Pringle who would later become Cain’s third wife. On the eve of Cain’s marriage to Pringle, Mencken wrote to Cain and warned him that he might begin to resent Pringle’s strong-minded personality. The comment, although tactless, proved to be quite prophetic as Cain’s stormy marriage to Pringle lasted only two years. Cain himself had been very close to Sara, although whether this was in any way romantic I don’t know. Cain was, to misquote John Inverdale, ‘never a looker’, but he seemed to have no problem in attracting beautiful women. As his biographer Roy Hoopes diplomatically put it, he was the type to come home ‘with lipstick on his collar’, although he was devoted to his fourth wife Florence Macbeth. Cain and Sara enjoyed the occasional dinner, and he recognised in her qualities that Mencken found so attractive. She had a quick wit and a wicked sense of fun, and this derived partly from the fact that she was such a good listener. Cain wrote that she could ‘see through most people’, and this helped Mencken to shed some of his more fair-weather friends. Perhaps Mencken had been yearning for this form of big lifestyle change for some time, as Rodgers writes that Cain believed that Mencken delayed marrying Sara until after the death of his domineering mother Anna. During one of her many illnesses Mencken recommended a clinic to Sara that Cain had attended when he was battling lung problems, and a few months after Sara’s death, Cain visited Mencken only to find him in a sad state, ‘wandering through the rooms, talking nonstop, almost mechanically.’

These are a few sketches of Cain I enjoyed taking from the book, but Mencken and Sara is about the two titular protagonists, and it is a informative, moving and witty read, which I would recommend to anyone interested in the history or literature of the era.