Ellroy and Hammett: The Tory and the Communist

How can two writers with such diametrically opposed political views seem to share a similar worldview? James Ellroy has often tried to portray the birth of American crime fiction as a stylistic struggle between Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, with Ellroy himself drawing the bulk of his writing inspiration from Hammett. It’s a rather simplistic interpretation, but still, it resonates. In one of the interviews I conducted with him, Ellroy said:

How can two writers with such diametrically opposed political views seem to share a similar worldview? James Ellroy has often tried to portray the birth of American crime fiction as a stylistic struggle between Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, with Ellroy himself drawing the bulk of his writing inspiration from Hammett. It’s a rather simplistic interpretation, but still, it resonates. In one of the interviews I conducted with him, Ellroy said:

I think he [Chandler] was lightweight compared to Dashiell Hammett. And I think that the language is overripe, the philosophy is gasbag. He came out of L.A., and he wrote in the first person. And it’s the L.A. of my early childhood and the L.A. before my birth, which is intensely romantic to me. And I sure as shit loved the books while I read them, but Hammett and Cain and Ross Macdonald have held in better in my mind. And I had to reread a little Hammett, because I wrote the Everyman Library introduction to one of their volumes, and was amazed at how my sensibility of the goon and the political fixer and the bagman and the hatchet man strike-breaker came out of that.

This ‘sensibility’ that Ellroy and Hammett share in their writing seems all the more remarkable given that Ellroy is a self-styled Tory and Hammett was a Communist. Both men’s political views informed their work, and both men, remarkably, share the same dark vision of America, where violence and corruption are ingrained into the political process and the public’s daily life. For Ellroy, Hammett’s greatest work was his ultra-violent indictment of industrial capitalism Red Harvest (1929), wherein his nameless detective the Continental Op is called on by the ailing newspaper czar old Elihu Wilsson to solve the murder of his son and clean up the mining town of Personville, which the Op is quick to christen Poisonville. From the very first page of Red Harvest, the reader will discern that they are entering a world where the normal rules don’t apply. The Op wanders from one hyperbolically violent scene to another as the characters settle their differences with bullets and dynamite. There is virtually no moral distinction in the narrative between politicians, gangsters and businessmen. As Ellroy put it in article on Hammett for the Guardian, ‘his workmen heroes refuse to soliloquise or indict – they know the game is rigged and they’re feeding off scraps of trickle-down graft.’ Even the detective himself must operate on this level, and in one of the most disturbing scenes he awakes from a surreal dream to find himself implicated in the brutal murder of the sultry but shopworn Dinah Brand.

I opened my eyes in the dull light of morning sun filtered through drawn blinds.

I was lying face down on the dining-room floor, my head resting on my left forearm. My right arm was stretched straight out. My right hand held the round blue and white handle of Dinah Brand’s ice pick. The pick’s six-inch needle-sharp blade was buried in Dinah Brand’s left breast.

She was lying on her back, dead. Her long muscular legs were stretched out towards the kitchen door. There was a run down the front of her right stocking.

Slowly, gently, as if afraid of awakening her, I let go of the ice pick, drew in my arm, and got up.

To the extent that Hammett was a direct influence on his writing, Ellroy has tried to transplant elements of Poisonville into his portrayal of 1940s and 50s Los Angeles. This was never more apparent than in White Jazz (1992), his most ahistorical novel, in which psychopathic killings and Mob-related violence push LA to the brink of anarchy. However, by the denouement, order has been restored and much of the corruption in the LAPD is still in place. I believe one scene may be inspired by the murder of Dinah Brand. The leading character and narrator of the novel, LAPD Lieutenant Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klein, is heavily drugged and coerced into murdering fellow policeman Johnny Duhamel, essentially recreating the scenario of Red Harvest wherein the protagonist is unwittingly implicated in a murder, compromising his ability to go after the villains because there is no differentiation between him and them. Of course, neither character is an angel before the staged murder, with Klein having already committed several murders for the Mafia. The murder is taped and a horrified Klein watches the killing on film:

I thrashed – futile – sticky tape, no give.

A white screen.

Cut to:

Johnny Duhamel naked.

Cut to:

Dave Klein swinging a sword.

Zooming in – the sword grip: SSGT D.D. Klein USMC Saipan 7/24/43.

Cut to:

Johnny begging – ‘Please’ – mute sound.

Cut to:

Dave Klein thrashing – stabbing, missing.

Cut to:

A severed arm twitching on wax paper.

Klein narrates the scene as though he is the director or screenwriter, giving technical details such as ‘Cut to’. Ellroy not only breaks downs the barriers between cops and criminals, but also through Klein’s clipped, staccato first-person narration, he implicates himself in the anarchic madness of the text. It is another factor which links him to Hammett, and explains why he regards him more highly than Chandler:

Chandler wrote the man he wanted to be – gallant and with a lively satirist’s wit. Hammett wrote the man he feared he might be – tenuous and sceptical in all human dealings, corruptible and addicted to violent intrigue.

Ellroy is impressed by the contradictions of Hammett’s personality, describing it as ‘the Manoeuvre’ and dubbing him ‘the Poet of Collision’. Red Harvest was inspired by Hammett’s experiences as a Pinkerton operative, and he was once allegedly offered $5,000 to perform a contract murder. But his left-wing views were not entirely formed by his work, and he appears not to have a sudden conversion, rather as Ellroy put it ‘He stayed because he loved the work and figured he could chart a moral course through it. He was right and wrong. That disjuncture is the great theme of his work.’ Communism, that most inflexible of ideologies, did not negate Hammett’s patriotism, as his service during the Second World War indicates. Ellroy called it a ‘deep and troubled love for America’, but one that also made him an apologist for the Soviet Union. Ellroy’s Toryism is more knowingly rooted in disjuncture than Hammett’s Communism, and this awareness leads to greater nuance. Sure, Ellroy may behave like a right-wing nut at book readings or on chat shows, but that is part performance, as he refines his act as the wild man of American crime fiction. A closer examination of Ellroy’s political views reveal him to be a moderate conservative with a more optimistic view of his country than Hammett ever held. Hammett thought the universe was chaotic and therefore rules were arbitrary. Ellroy’s religious beliefs (which I will explore further in another post) allowed for a greater sense of a journey and meaning to emerge even from the violent chaos of White Jazz. Hammett believed the dehumanising nature of capitalism made people indistinct on several levels, but for Ellroy corruption fired characters individualism.

They may be generations apart, but Ellroy and Hammett were linked by their own disjuncture: Hammett the Communist, who thought order was impossible, Ellroy, the modern-day Tory and one of Hammett’s greatest admirers.

The Meaning of Perfidia: James Ellroy’s New Novel

We now know a little bit more about the plot of James Ellroy’s forthcoming novel, but the significance of the title, Perfidia, has not, to my knowledge, been commented on. Put simply ‘perfidia’ is the Spanish word for perfidy, meaning treachery or betrayal. It is also the name of a very popular song by the Mexican composer Alberto Dominguez released in 1939. The impact of the song on popular culture has been huge. It has been recorded by artists such as Julie London, Glenn Miller and Nat King Cole to name just a few and has appeared on the soundtrack of many movies, notably Now Voyager (1942) and Casablanca (1942). Ellroy has referenced the song before. In The Black Dahlia (1987), the lovers Kay Lake and Lee Blanchard dance to ‘Perfidia’ on New Year’s Eve, 1947. Their best friend Dwight ‘Bucky’ Bleichert looks on, realising he has fallen in love with Kay:

On New Year’s Eve, we drove down to Balboa Island to catch Stan Kenton’s band. We danced in 1947, high on champagne, and Kay flipped coins to see who got last dance and first kiss when midnight hit. Lee won the dance, and I watched them swirl across the floor to “Perfidia,” feeling awe for the way they had changed my life. Then it was midnight, the band fired up, and I didn’t know how to play it.

Kay took the problem away, kissing me softly on the lips, whispering, “I love you, Dwight.” A fat woman grabbed me and blew a noisemaker in my face before I could return the words.

We drove home on Pacific Coast Highway, part of a long stream of horn-honking revelers. When we got to the house, my car wouldn’t start, so I made myself a bed on the couch and promptly passed out from too much booze. Sometime toward dawn, I woke up to strange sounds muffling through the walls. I perked my ears to identify them, picking out sobs followed by Kay’s voice, softer and lower than I had ever heard it. The sobbing got worse – trailing into whimpers. I pulled the pillow over my head and forced myself back to sleep.

‘Perfidia’ is an apt song for the complicated trinity of Bucky, Kay and Lee Blanchard. The lyrics refer to a love ripped apart by betrayal ‘To you my heart cries out “Perfidia” / For I find you, the love of my life / In somebody else’s arms’. The behaviour of Ellroy’s characters in the above quote suggests an unusual interaction and reliance on trade-offs. Bucky loses the dance but wins the kiss, and it is the kiss that is the most revealing, as Bucky now knows that his outwardly platonic friendship with Kay is anything but.

It might be tempting to think that as Ellroy was referencing ‘Perfidia’ in his work as far back as 1987, his plans for his latest novel started then. That would be over-reading however. Ellroy only decided to write a Los Angeles Quartet after the success of The Black Dahlia, and he has not revealed precisely when he decided to write Perfidia, the first novel of a Second LA Quartet which will be prequels to the original (although the short stories which appear in Hollywood Nocturnes (1994) are basically mini-prequels to the first Quartet, which suggests he has been toying with the idea for some time). I think it likely that Ellroy must have heard ‘Perfidia’ when he was growing up in LA in the 1950s, and it stayed with him. He referenced the song in The Black Dahlia and kept alive the idea he would return to it one day, and now he has. This reworking is somewhat similar to his use of the title The Cold Six Thousand, which was originally planned for the fourth Lloyd Hopkins novel, but after he abandoned that project, Ellroy used it fifteen years later as the title of the second novel in the Underworld USA trilogy.

Perfidia is due to be released in the autumn, Amazon has the exact date as 9 September.

A New Year and the End of an Era

Last month I had the viva for my thesis and I passed. I do have some corrections to make, but I have essentially completed my PhD. I’m planning to continue publishing my research on James Ellroy both on this blog and, hopefully, in book form. Stay tuned. Looking back over my seven years of doctoral study, I’ve been thinking a lot about crime novels that gave me a great deal of pleasure in between the endless drafting, redrafting and editing of my thesis, so I thought I’d talk a little about them here.

White Jazz by James Ellroy

I’m a fan of all of Ellroy’s novels and my favourite varies according to my mood. Right now I’m thinking it’s White Jazz (1992) as its just the most daring and subversive in terms of its depiction of LA and noir as a genre. The plotting is labyrinthine and almost impossible to summarise in just a few words. Narrated by LAPD Lieutenant Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klein, White Jazz involves Mob contract killings, the Battle of Chavez Ravine, historical characters (including Jack Dragna, Mickey Cohen, Sam Giancana and Howard Hughes), a beautiful femme fatale and a grade Z horror movie. The first time I read this novel, I was shaking with excitement, exhilaration and fear when I got to the last page. David Peace summed up the novel’s power: ‘His novel White Jazz was the Sex Pistols for me. It reinvented crime writing and I realised that, if you want to write the best crime book, then you have to write better than Ellroy.’

I’m a fan of all of Ellroy’s novels and my favourite varies according to my mood. Right now I’m thinking it’s White Jazz (1992) as its just the most daring and subversive in terms of its depiction of LA and noir as a genre. The plotting is labyrinthine and almost impossible to summarise in just a few words. Narrated by LAPD Lieutenant Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klein, White Jazz involves Mob contract killings, the Battle of Chavez Ravine, historical characters (including Jack Dragna, Mickey Cohen, Sam Giancana and Howard Hughes), a beautiful femme fatale and a grade Z horror movie. The first time I read this novel, I was shaking with excitement, exhilaration and fear when I got to the last page. David Peace summed up the novel’s power: ‘His novel White Jazz was the Sex Pistols for me. It reinvented crime writing and I realised that, if you want to write the best crime book, then you have to write better than Ellroy.’

I only started reading P.D. James in the last year or two, and I think she is just one helluva of a great writer. The Cordelia Gray novels are excellent, the Adam Dalgliesh novels are even better, but my favourite so far is the standalone work Innocent Blood (1980). Phillipa Palfrey is the adopted daughter of a well- to- do couple. When Phillipa takes advantage of a new law allowing her to contact her biological parents, she discovers they were convicted of the rape and murder of a young girl. What follows is not a straight forward murder mystery, but a revealing character study with plenty of suspense. A sub-plot involves the murdered girl’s father plotting his revenge. James’ conservatism is evident in the early chapters, and she makes a strong case that you can’t legislate human behaviour. It is clear from her writing, however, that James understands human behaviour, and I can’t think of another novelist who can write about England so well.

The Laughing Policeman by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö

The Laughing Policeman by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö

I’ve just got to include a Scandi crime novel, and The Laughing Policeman (1968) might just be the best Scandi crime novel of them all! A massacre on a bus in a Stockholm street has left eight people dead and world-weary detective Martin Beck is forced to investigate. It’s a complex case with shades of Agatha Christie’s The ABC Murders (1936), and the final twist is stunning. Jonathan Franzen wrote, ‘I’ve read The Laughing Policeman six or eight times. Each time I reach the final twist on the final page, I shiver afresh.’ He neglects too mention it’s also a very funny conclusion.

Double Indemnity by James M. Cain

Double Indemnity by James M. Cain

James M. Cain’s reputation rests on four classic novels The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), Serenade (1937), Mildred Pierce (1941) and Double Indemnity (1943). His later life was a sad story of a writer trying to build a more literary reputation while his career slowly crumbled. Double Indemnity, originally serialised by Liberty magazine in 1936, tells the story of an insurance agent and his lover plotting the murder of her husband to look like an accident and collect the insurance policy. Billy Wilder’s film adaptation is a classic, but he and screenwriter Raymond Chandler changed the ending. The ending to the film is still dark, but it doesn’t match the ending of the novel for sheer haunting beauty.

Smiley’s People by John le Carré

Smiley’s People by John le Carré

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) seemed to capture the anti-establishment mood of the Sixties; Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974) was a classic work inspired by the Cambridge Five, particularly Kim Philby; and A Perfect Spy (1986) is le Carré’s most autobiographical work. But my favourite novel has always been Smiley’s People (1979). The case is complex, beginning with the murder of an Estonian emigre and ex-agent of Smiley’s, but it is never impenetrable for the reader. The way Smiley pieces it together bit by bit (and working almost entirely on his own for much of the novel) is ingenious. This was le Carré’s goodbye to Smiley (he pops up again briefly in The Secret Pilgrim (1990)) and the character was never more intriguing, both gentle and kind but ruthless when he needs to be. The ending is brilliant too, but unlike White Jazz which made me feel like I’d been hit with a sledgehammer, Smiley is understated in his final confrontation with his Soviet nemesis Karla, and the novel is all the more quietly moving as a result.

Death Comes to Pemberley: Crime Fiction Meets Jane Austen

Telegraph critic Horatia Harrod described the recent BBC adaptation of P.D. James’ foray into Austen’s world as a ‘crime against literature’. I couldn’t disagree more.

Telegraph critic Horatia Harrod described the recent BBC adaptation of P.D. James’ foray into Austen’s world as a ‘crime against literature’. I couldn’t disagree more.

Instead, I would argue that both James’ novel and the BBC’s adaptation bring to Austen’s world an immediacy not present in the controlled world of the original. Lizzie, as a single woman, had few demands on her time in Pride and Prejudice, allowing her to be a somewhat aloof though humorous observer of human nature. This is not possible for a woman moved to the centre of the action, as Lizzie is in Death Comes to Pemberley. For Elizabeth Darcy, the violent death of a soldier in Pemberley woods disrupts the stability of her role as mistress of Pemberley: her marriage to Darcy comes under particular strain (emphasized more in the adaptation than the novel) as the demons from her past– her uninvited sister Lydia, Wickham’s initial deception of Lizzie and her social standing (Lady Catherine de Burgh is always a funny reminder)– rise up to haunt her. Darcy wonders if in overcoming his prejudices to her family, he has made a sacrifice of his honour by associating himself with a family that will ultimately destroy Pemberley.

This disruption to the Darcys’ everyday lives also allows for more compassion for Lydia and Wickham, the latter ends up on trial for the murder of the soldier. There are times I find Austen to be a bit cold, especially when commenting on human weakness, but the BBC’s adaptation of Death Comes to Pemberley offered reasons why Lydia and Wickham might love each other besides their vanity. Rather than being cast aside as a beautiful, foolish girl and her rake husband, the audience had a glimpse of what being married to Wickham must be like. In one of the most moving scenes of the mini-series, Elizabeth tries to tell Lydia of Wickham’s affair with a young woman hoping to soften the blow, but Lydia interrupts, preferring to hear it from gossips so that she can dismiss it as false, rather than accept it from her sister as truth. The frivolous is a form of protection rather than a weakness to be mocked.

P.D. James, I would argue, also offers us a wider scope within the fictional world. Rarely does Austen venture beyond the country-house: the villain of Pride and Prejudice, George Wickham, has his nefarious deeds relayed through gossip, letter or through retelling– the same goes for Frank Churchill and John Willoughby in Emma and Sense and Sensibility respectively. Here, the courtroom and the crime are made central, with powerful first-hand experiences. But not only is Death Comes to Pemberley arguably a more exciting novel than Pride and Prejudice, in the novel, James also connects Austen’s fictional worlds: Wickham, for instance, has worked for Sir Walter Elliot (from Persuasion), and his illegitimate child will be adopted by Miss Harriet Smith (now Mrs Martin) and will play with Mr and Mrs Knightley’s children (from Emma).

Lastly, James’ adaptation has been accused of showing Georgian policing to be inadequate, and not just in comparison to today’s standards. However, this is often the aim of crime fiction, even the police procedural sub-genre can show the shortcomings of police work. In crime fiction, journalists (Stieg Larsson’s Girl Who novels, Liza Marklund’s Annika Bengtzon character), private detectives, and gifted individuals (Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple) step-in where the law has fallen short. Crime fiction is fascinating in that it often critiques the very law it is trying to uphold by highlighting its inadequacies, a trait shared with Austen. I think the BBC’s adaptation understood this, asking ‘What is Justice?’ and ‘What is Duty?’ on a personal and collective level.

I enjoyed both book and adaptation, although I think the BBC made some changes to James’ material to accommodate fans of the 1995 Pride and Prejudice mini-series, such as having Elizabeth’s mother and long suffering father present (rather than Jane and Bingley) when the murder occurs (leading to some much-appreciated comic relief) and the rather badly done, cringe-worthy ending, with Elizabeth revealing to Darcy her second pregnancy (in the book she’s already had two children) and Georgiana’s beau riding up with his shirt undone for that telling embrace by the lake.

If anything, I felt that James was a bit too interested in getting the historical aspects of the courtroom right in the novel that it lost some of its dramatic edge; however, I think for Austen and James fans, the adaptation and novel successfully merged the work of two of Britain’s best-loved authors.

Season’s Greetings

This blog will be quiet over the next few weeks. I hope you all have a wonderful Christmas and happy new year where the only crime you experience is in the pages of a paperback novel. I’m hopeless at keeping up with new releases as I prefer to dip into crime fiction’s endless back catalogue, so next on my reading list for the holidays is PD James’ Innocent Blood (1980) and Mark Billingham’s Rush of Blood (2012), and I’ve also got lots of reading to do on the First World War as I’m writing an article on the subject for the British Politics Review. Thanks for reading over 2013. I’ll try and keep the posts just as interesting in 2014 to keep you coming back!

A Swedish Crime Fiction Christmas: The Bomber by Liza Marklund

If you haven’t already chosen a good book to read this holiday season, I’d heartily recommend Liza Marklund’s Scandinavian thriller The Bomber (1998). Marklund’s tightly-plotted and well-written tale is set in Stockholm in the run up to the holidays, a stylistic choice which heightens the tension for her main protagonist, a thirty-something wife and mother and newly appointed chief crime reporter Annika Bengtzon. When a psychopath starts a bombing campaign targeting buildings related to the upcoming Stockholm Olympics, Bengtzon finds herself against the clock in more ways than one. Marklund cleverly structures the chapters around the countdown to Christmas beginning with ‘December 18th’, a technique which shows Bengtzon’s real struggle: balancing the competing demands on her time of being a good boss, a star reporter, a loving wife and mother. After a particularly rough day, she muses, ‘Not only was she an unbalanced head of section and a useless reporter, but she was a rotten wife and a hopeless mother, too.’ Such frankness is particularly endearing, and emerges in different forms, such as when she forgets to shower after a long shift and wonders if her shirt smells and feels guilty about not baking Christmas buns with her children when they try her patience. One of the most attractive aspects of Scandinavian dramas is their apparently flawed heroes/heroines and Annika Bengtzon is reassuringly normal.

If you haven’t already chosen a good book to read this holiday season, I’d heartily recommend Liza Marklund’s Scandinavian thriller The Bomber (1998). Marklund’s tightly-plotted and well-written tale is set in Stockholm in the run up to the holidays, a stylistic choice which heightens the tension for her main protagonist, a thirty-something wife and mother and newly appointed chief crime reporter Annika Bengtzon. When a psychopath starts a bombing campaign targeting buildings related to the upcoming Stockholm Olympics, Bengtzon finds herself against the clock in more ways than one. Marklund cleverly structures the chapters around the countdown to Christmas beginning with ‘December 18th’, a technique which shows Bengtzon’s real struggle: balancing the competing demands on her time of being a good boss, a star reporter, a loving wife and mother. After a particularly rough day, she muses, ‘Not only was she an unbalanced head of section and a useless reporter, but she was a rotten wife and a hopeless mother, too.’ Such frankness is particularly endearing, and emerges in different forms, such as when she forgets to shower after a long shift and wonders if her shirt smells and feels guilty about not baking Christmas buns with her children when they try her patience. One of the most attractive aspects of Scandinavian dramas is their apparently flawed heroes/heroines and Annika Bengtzon is reassuringly normal.

In The Bomber, Marklund explores similar questions to Steig Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo in regards to gender, but where Larsson more sharply contrasts his ‘Men who Hate (and do not hate) Women‘, Bengzton describes a world in which sexism is the last resort of dinosaurs in the office, men, who in their fifties have neither the skill nor the dedication of Bengtzon and resort to a campaign of harassment when she is promoted above them. Bengtzon’s husband, like Birgitte Nyborg’s in the Danish drama Borgen, is the main caregiver to the children despite his own role in local politics, and the family purposefully chose a nursery where half of the workers are male. Despite this social renegotiation of traditional gender roles, the difficulties for women are still apparent. Unlike the coasting male reporters, the women in the novel must fight their ground, either by being exceptionally dedicated to their work and foregoing or discarding their family life, or, as with Bengzton, by reaching some kind of stressful compromise. The tension is too much for some, and the results are horrific.

Bent Coppers in Fact and Fiction

An ex-copper recommended two books to me recently, GF Newman‘s Sir, You Bastard (1970) and Bent Coppers: The Inside Story of Scotland Yard’s Battle Against Police Corruption (2004) by Graeme McLagan. I was particularly intrigued by the Newman title as most people I’ve met who worked with the police cannot stand detective fiction on the grounds that it is almost never realistic, but Sir, You Bastard, I was assured, is different. The novel covers seven years in the career of Terry Sneed, a man who who has had a meteoric rise through the police to the rank of Detective Inspector by being ruthless, intelligent, corrupt, despicable and charming in equal measure. The prologue and epilogue show Sneed with his career, and indeed his entire future in doubt, but the rest of the novel is a gripping, albeit loosely plotted journey of his ascent with chapter titles indicating his promotions ‘Detective Constable‘, ‘Detective Sergeant‘ etc. Sneed’s corruption develops from pulling cruel pranks on drivers as an uniformed policeman to brutal interrogations and abusing his position with informants. The milieu and police dialect is meticulously researched and sometimes feels like a British version of the work of Joseph Wambaugh, but Wambaugh’s cops usually grow weary and exhausted by the corruption or the drudgery of police work. Sneed, on the other hand, becomes frighteningly more confident and powerful as the story progresses.

An ex-copper recommended two books to me recently, GF Newman‘s Sir, You Bastard (1970) and Bent Coppers: The Inside Story of Scotland Yard’s Battle Against Police Corruption (2004) by Graeme McLagan. I was particularly intrigued by the Newman title as most people I’ve met who worked with the police cannot stand detective fiction on the grounds that it is almost never realistic, but Sir, You Bastard, I was assured, is different. The novel covers seven years in the career of Terry Sneed, a man who who has had a meteoric rise through the police to the rank of Detective Inspector by being ruthless, intelligent, corrupt, despicable and charming in equal measure. The prologue and epilogue show Sneed with his career, and indeed his entire future in doubt, but the rest of the novel is a gripping, albeit loosely plotted journey of his ascent with chapter titles indicating his promotions ‘Detective Constable‘, ‘Detective Sergeant‘ etc. Sneed’s corruption develops from pulling cruel pranks on drivers as an uniformed policeman to brutal interrogations and abusing his position with informants. The milieu and police dialect is meticulously researched and sometimes feels like a British version of the work of Joseph Wambaugh, but Wambaugh’s cops usually grow weary and exhausted by the corruption or the drudgery of police work. Sneed, on the other hand, becomes frighteningly more confident and powerful as the story progresses.

Newman is a great writer, quite eccentric in his personal views by all accounts, and sets a cruelly ironic and blackly comic tone with apparent ease. Sneed’s Colombian mistress Billie, dismissed as a ‘spade’ by his racist colleagues, contemplates her love for a very bad man while watching a television police drama that she knows from personal experience is completely unrealistic:

The flickering colours seemed miles away in the darkened room. Billie had noticed it before; her gaze would become fixed as thoughts crossed other frontiers, and suddenly awareness o the TV would be gone. Through lifting the shutter from her eyes, it was easy picking up the threads of the plot again; the screen didn’t have to be watched or the sound listened to; it was always the same basic struggle, Good defeating Evil.

Billie watched two men in the police Buick speeding in pursuit of Evil; the chase signified that the end was nigh; Good always triumphed after the chase. In a paroxysm of sound, Evil’s car crashed into a wall, so conveniently placed. But the audience wasn’t released. Evil escaped, and ran to the fire-escape between his ricocheting bullets, his thirteen-year-old hostage, dressed symbolically in white, preventing the Good Joe Detective from shooting back. Evil climbing up the building was symbolic of his searching for God, but his reckless shooting killed thirty-nine cops, showing that his ascent heavenwards was insincere. With all fifty bullets spent, Evil threatened to throw his hostage over the edge if unscathed Good came any closer. One last emphatic appeal by Good, to no avail, and, the hostage notwithstanding, the perilous precipice-struggle ensued, Evil meeting a well-deserved fate by falling down to Hell. After the sound of Evil’s descent, Good took the trembling virgin comfortingly in his arms and, in an intimate aside with two-hundred-million viewers across the world, he imparted the message. All that was missing was a jingle: “Help our police, they’re your friends.” Billie switched off at the expense of a girl unable to get a boy-friend because she used the wrong toothpaste. For a moment she wished Terry was like that policeman hero, not especially because he was good or honest, but because he was certain to triumph. She wanted Terry always to triumph – neither for the sake of winning nor for her sake, but for Terry’s sake and what falling would do to him.

Graeme McLagan’s Bent Coppers was an interesting book to read after Newman’s fictional account of police corruption. However, his account of Scotland Yard’s attempts to confront corruption, which roughly covers the early 1990s to 2004 but also mentions cases before this timeframe, met with controversy. McLagan was sued by ex-police officer Michael Charman for libel. McLagan lost the case but subsequently won on appeal citing the ‘Reynolds Defence’. It was easy to see why many in the London Met, and even book critics, were generally upset by McLagan’s work. There is not a single footnote or reference in over four hundred pages of text. McLagan doesn’t even refer to other books on the same subject, only his own Panorama documentaries. He does refer to off the record interviews and police transcripts that have come his way but, perhaps for good reason, he was unable to reference them. There is also a stylistic problem with the writing: non-fiction subjects generally present issues with repetition but Bent Coppers really does go around in circles in its more tedious moments. That said, there are many fascinating moments to make it worth reading. The case of the detective agency Southern Investigations’ shady relationship with both the police and press seems particularly enlightening in the wake of the Leveson Inquiry, a fact the author has picked up on since:

It was believed that Southern had played a part in setting up newspaper stings. It not only hired out expensive electronic listening devices to the media, but also delivered sting ‘packages’. These kept everyone happy, apart from the victims, but who cared about them? Such a sting could take place, for example, if the agency received information from one of its police contacts that someone was dealing in drugs. Southern would then mount its own sting, planting drugs on the man or arranging for someone to pretend to want to buy drugs. A newspaper would be tipped off to be at the sting to obtain evidence. On the eve of publication of the story, the newspaper would hand its evidence over to the police, who would then move in and arrest the criminal. The newspaper got its exclusive. The police were happy because they were seen to be catching criminals. Southern was paid for its help, and the agency passed on some of the money to the officer who had supplied the original information. This kind of scam worked for a while, and no one seemed too concerned.

Amid all this talk of factual and fictional corruption, however, let me end on an optimistic note. At last month’s Remembrance Day service on the steps of St George’s Hall, Liverpool, the crowds gave the police in attendance the same level of warm and enthusiastic applause as they gave to the military veterans. The reputation of the police may have taken a battering in recent years with the Hillsborough revelations to the borderline farce of Plebgate, but that hasn’t dimmed our gratitude for the good work that they do.

Rogue Cops and Shakedown Artists – The Nature of Conspiracy Theories

In an article for the Evening Standard Matthew d’Ancona looks at the impending anniversary of the assassination of JFK and attacks the culture of conspiracy theories and the anti-politics mood that tragic and seismic event caused:

In Kennedy’s case, the bequest of his violent death in Dallas is quite specific: the grassy knoll, the “magic bullet”, the “second” Lee Harvey Oswald, the book depository, the New Orleans connection, the Mob, the Cubans, and shelves full of studies supposedly proving once and for all that JFK could not have been the victim of a lone gunman. According to a poll conducted in April, a clear majority of Americans still believes that there was a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy, a folkloric orthodoxy reflected and reinforced most luridly in Oliver Stone’s epic movie, JFK (1991).

Into the yawning gap between the official Warren Commission and the prevailing conspiracy theories about Kennedy’s death tumbled postwar political culture. Vietnam and Watergate merely completed the process of disenchantment. Half a century of sleuthing, reconstructions, legitimate inquiry, pure conjecture, science and pseudo-science has become symbolic of a fundamental change in the way we see politics and politicians. Much more than a presidency ended in Dallas in November 1963.

As David Aaronovitch shows in his brilliant book, Voodoo Histories, conspiracy theories are at the heart of contemporary history and the way that we explain what happens to us and around us. The web has provided theorists on all budgets with the means of communicating instantly, sharing their often ludicrous ideas, and amplifying those that resonate in their digital communities.

I broadly agree with d’Ancona’s analysis here. As a teenager I was hooked on several conspiracy theories (I was never fanatic about them, mind you), but as I got older, I gradually shed these beliefs. If there is no proof, then there is no reason to believe in a conspiracy. Still, d’Ancona is rather condescending towards people’s fascination with conspiracies and overlooks how intelligent people can be inclined towards conspiracy theories. I’ve recently finished reading The Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5 and was shocked by the chapter that dealt with the paranoia that inflicted Harold Wilson in his final days as Prime Minister in 1976 as he became completely obsessed with a false belief that the intelligence services were spying on him.

Then again, as much as we agonise over conspiracy theories of events in Dealey Plaza fifty years ago, there have been other shocking conspiracies exposed that are just as disturbing as the thought that Lee Harvey Oswald was not the lone gunman on November 22, 1963. Few people, I suspect, thought Richard Nixon would ever have to resign the Presidency of the United States due to events surrounding a burglary at the Watergate Hotel. But the term ‘conspiracy’ is not as easy to define as we might think. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was a conspiracy, although we tend not to think of it as such today as the word has become associated with shadowy intelligence agencies and reclusive billionaires secretly running the world. A plausible conspiracy theory needs to have strict borders, otherwise it veers off into the deranged ramblings of, say, David Icke.

One of my favourite novels concerning the Kennedy era and his assassination is James Ellroy’s American Tabloid (1995). In his prologue to the novel, Ellroy states his intention is to demythologise the ‘sainthood’ of Kennedy, and he also manages to demythologise a certain strand of conspiracy theory regarding Kennedy while rejecting the lone gunman explanation and presenting his own conspiracy narrative. As he put it in an interview with Ron Hogan:

I think organised crime, exiled factions, and renegade CIA killed Jack the Haircut. I think your most objective researchers do as well. When Oliver Stone diverged from that to take in the rest of the world (Lyndon Johnson, the Joint Chiefs of Staff), I lost interest.

Is Ellroy correct in his vision of the JFK assassination? My feeling today is no. The truth, in its simplicity, is just as remarkable as any fictional portrayal. As Hugh Aynesworth, a reporter who witnessed the assassination, put it in a recent interview with the Telegraph: “We all love a conspiracy. No one wants to believe two nobodies [Oswald and Jack Ruby] could change the course of world history. But they did.” In a way though, this doesn’t impair the work of Ellroy as he is writing fiction, whether it ties to his or the reader’s beliefs is secondary as his portrayal of the era is gripping and convincing. You don’t have to believe in conspiracy theories to know that in the era of the late 1950s and 1960s, organised crime operated with relative impunity and Intelligence agencies had far less accountability to government than they do today. The prologue to American Tabloid could almost be compatible with Aynesworth’s anti-conspiracy stance. Ellroy argues that the men who defined the age were not in any sense powerful men who could control the country as simply as moving pieces on a chessboard, rather:

Is Ellroy correct in his vision of the JFK assassination? My feeling today is no. The truth, in its simplicity, is just as remarkable as any fictional portrayal. As Hugh Aynesworth, a reporter who witnessed the assassination, put it in a recent interview with the Telegraph: “We all love a conspiracy. No one wants to believe two nobodies [Oswald and Jack Ruby] could change the course of world history. But they did.” In a way though, this doesn’t impair the work of Ellroy as he is writing fiction, whether it ties to his or the reader’s beliefs is secondary as his portrayal of the era is gripping and convincing. You don’t have to believe in conspiracy theories to know that in the era of the late 1950s and 1960s, organised crime operated with relative impunity and Intelligence agencies had far less accountability to government than they do today. The prologue to American Tabloid could almost be compatible with Aynesworth’s anti-conspiracy stance. Ellroy argues that the men who defined the age were not in any sense powerful men who could control the country as simply as moving pieces on a chessboard, rather:

They were rogue cops and shakedown artists. They were wiretappers and soldiers of fortune and faggot lounge entertainers. Had one second of their lives deviated off course, American history would not exist as we know it.

It’s time to demythologize an era and build a new myth from the gutter to the stars. It’s time to embrace bad men and the price they paid to secretly define their time.

Here’s to them.

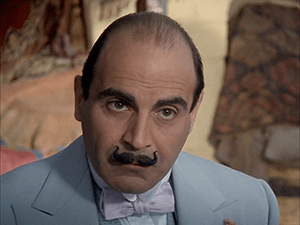

Praise for Poirot

In her autobiography Agatha Christie describes how the influx of Belgian refugees to Britain at the start of the First World War provided her with the inspiration for her famous fictional detective Hercule Poirot:

I reviewed such detectives as I had met and admired in books. There was Sherlock Holmes, the one and only–I should never be able to emulate him. There was Arsene Lupin– was he a criminal or a detective? Anyway, not my kind. There was the young journalist Rouletabille in The Mystery of the Yellow Room– that was the sort of person whom I would like to invent: someone who hadn’t been used before. Who could I have? A schoolboy? Rather difficult. A scientist? What did I know of scientists? Then I remembered our Belgian refugees. We had quite a colony of Belgian refugees living in the parish of Tor. Everyone had been bursting with loving kindness and sympathy when they arrived. People had stocked houses with furniture for them to live in, had done everything they could to make them comfortable. There had been the usual reaction later, when the refugees had not seemed to be sufficiently grateful for what had been done for them, and complained of this and that. The fact that the poor things were bewildered and in a strange country was not sufficiently appreciated. A good many of them were suspicious peasants, and the last thing they wanted was be asked out to tea or have people drop in upon them; they wanted to be left alone, to be able to keep to themselves; they wanted to save money, to dig their garden and to manure it in their own particular and intimate way.

Why not make my detective a Belgian? I thought. There were all types of refugees. How about a refugee police officer? A retired police officer. Not a young one. What a mistake I made there. The result is that my fictional detective must really be well over a hundred by now.

Anyway, I settled on a Belgian detective. I allowed him slowly to grow into his part. He should have been an inspector, so that he would have a certain knowledge of crime. He would be meticulous, very tidy, I thought to myself, as I cleared away a good many odds and ends in my own bedroom. A tidy little man. I could see him as a tidy little man, always arranging things, liking things in pairs, liking things square instead of round.

It’s especially interesting to think of the war refugee inspiration for Poirot the Sunday before Remembrance Day. It is only a few days before the last episode of the television series Agatha Christie’s Poirot is broadcast. It feels as though we are saying goodbye to an era, and it’s worth looking back to where it all began, in print and on television. When David Suchet made his debut appearance as Poirot in 1989, Margaret Thatcher was still in power, the World Wide Web had not yet been invented, and Christie’s novels from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction would have seemed hopelessly out of date for television. Only a few years later, detective dramas such as Between the Lines, Prime Suspect and Cracker burst onto our television screens offering a gritty, realistic depiction of police corruption and crime in contemporary Britain. Suchet’s interpretation of Poirot built an audience and reputation slowly and steadily. Albert Finney and Sir Peter Ustinov had given entertainingly hammy performances as Poirot. Suchet was informed by the Christie family that they were sick of seeing Poirot portrayed as a caricature and wanted to see a version closer to the character in the books. Suchet did not let them down. Although his Poirot is definitely an eccentric, there is depth and humanity to the character which has made him so durable and compelling. His performance in the 2010 episode of Murder on the Orient Express, which gives an interesting twist on a story which was already ingrained in the public consciousness, was one of the most moving pieces of acting I have seen in television.

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case will be the seventieth and final episode of the Agatha Christie’s Poirot productions which has seen every major work by Christie featuring the Belgian detective adapted to television. I’ll be watching it on Wednesday night, and I don’t doubt there’ll be a little sadness that such a superb series has finally come to an end.

Elmore Leonard’s Rules of Writing: Avoid Prologues

If you ever want a quick reminder of the recently departed Elmore Leonard’s genius, it’s always worth revisiting his 10 Rules of Writing. The most oft quoted rule is the closing one, which Leonard said, ‘sums up the 10’. Put simply: ‘Try to leave out the part the readers tend to skip’. But for this post I want to look at rule 2, Avoid Prologues:

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

I can’t fault Leonard’s argument. and you can see how it connects to his own work. In his best novels 52 Pickup (1974) and Killshot (1989) there is no real mystery. Instead, Leonard presents a series of bizarre, violent and loosely connected events. Who needs a prologue for that? However, let’s look at two examples of prologues in a crime novel, one written long before Leonard set down his rules of writing. Firstly, True Confessions (1977), John Gregory Dunne’s novel loosely based on the Black Dahlia case. The novel begins with the heading ‘NOW’ and contains the first-person prologue of retired detective Tom Spellacy. The prologue, as its title states, is set in the present day, and Spellacy is musing on the discovery of the corpse of Lois Fazenda, dubbed the ‘Virgin Tramp’ in the novel. Fazenda is Dunne’s stand-in for Elizabeth Short, aka The Black Dahlia:

Anyway, when I got there, Crotty was bending over the second half of Lois Fazenda. The top half. She was naked as a jaybird, both halves. There was no blood. Not a drop. Anywhere. Just this pale green body cut in two. It was too much for Bingo. He took one look at the top half and spilled his breakfast all over her titties, which is a good way to mess up a few clues. Not that it bothered Crotty. “You don’t often see a pair of titties nice as that,” was all he said. Respect for the dead, Crotty always used to say, was bullshit. Dead is dead.

This sets the tone for the dark, grisly humour which runs throughout the book. The next section is titled ‘THEN’, and is a third-person narrative set in the late 1940s. This forms the bulk of the novel and covers Spellacy’s original investigation. The epilogue reverts back to the ‘NOW’ heading, and Spellacy’s first-person voice. Dunne’s NOW/THEN present day/past setting of the novel is an example, I believe, of a prologue that works really well in a crime novel. Although strictly speaking it may not be a prologue at all. The first ‘NOW’ section covers twenty-four pages and is split over six chapters. A prologue always precedes the first chapter therefore just postponing the inevitable in Leonard’s view. However, the ‘THEN’ section also begins as chapter one. Also, this longer section is essentially the backstory to the present day Tom Spellacy we meet in the prologue and epilogue, reversing Leonards’ claim that ‘a prologue in a novel is backstory’.

Dunne’s use of prologue and epilogue is referenced in James Ellroy’s Blood’s a Rover (2009). The novel was Ellroy’s long awaited conclusion to the Underworld USA trilogy and was billed as covering American history from 1968 to 1972. The first two volumes of the trilogy, American Tabloid (1995) and The Cold Six Thousand (2001), covered 1958-1963 and 1963-1968 respectively. I’m sure more than a few Ellroy readers would have been surprised when they opened up the novel to find the heading ‘THEN’ followed by the first scene, an armed robbery written in the first-person, set in 1964. This is followed by the heading ‘NOW’, the first-person narration of Don ‘Crutch’ Crutchfield set in the present-day, then we cut to ‘THEN’ again (confused yet?) and things commence in 1968, the main five year time span of the novel, and back in third-person. We end with ‘NOW’ and we’re back with Crutchfield in the present day, oh and did I mention there’s an epigraph before the first ‘THEN’?

By and large I think Ellroy just about gets away with his rather complicated tribute to John Gregory Dunne, but you can see he’s veering dangerously close to what Leonard talked about when he said avoid, ‘a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword’. If you’re going to break the rules of the master, do it well.