Flashman and the Greatest Chronicler of the Victorian Age

The following article is taken from a talk I gave for Waterstones Lunchtime Classics series:

The character Flashman first appeared in the 1857 novel Tom Brown’s School Days written by Thomas Hughes. Hughes was a lawyer, judge, social reformer and Liberal MP. The novel is set at Rugby boarding school , which Hughes had attended, and he wrote the book for his young son who was about to attend. Hughes intended the book to be a treatise against bullying but also a celebration of school life. As the critic Naomi Lewis put it:

What makes the book live is that the whole thing is seen throughout from a boy’s view, and the boy who sees it relishes it all. Was there ever such a first day at school as Tom’s? After riding by coach through the frozen night (coffee and hard biscuit at three am.; pigeon pie and hot kidneys at 7:30) he is regaled with fearsome Rugby legends by the local John: watches two boys run a mile in 4 minutes 56 seconds; arrives at noon; goes on a tour with East; gets some new togs; takes part part in that vast rugger match (50 to 60 boys to a side – can it be?); is noticed by the giant head boy Brooke; has tea of toasted sausages; does his solo turn in the evening’s singing; gets his first impact of Doctor Arnold taking prayers and ends up being tossed in a blanket. No wonder that dayschool boys through the years have read the book with a sigh.

It’s a remarkably moral book: the sympathetic Tom and his schoolfriend’s nemesis is the bully Flashman, who roasts Tom over a fire and throws boys around in a strange game of blanket tossing. About halfway through the book, Flashman is abruptly expelled and the reader doesn’t see him again:

One fine summer evening Flashman had been regaling himself on gin-punch, at Brownsover; and, having exceeded his usual limits, started home uproarious. He fell in with a friend or two coming back from bathing, proposed a glass of beer, to which they assented, the weather being hot, and they thirsty souls, and unaware of the quantity of drink which Flashman had already on board. The short result was, that Flashy became beastly drunk. They tried to get him along, but couldn’t; so they chartered a hurdle and two men to carry him. One of the masters came upon them, and they naturally enough fled. The flight of the rest excited the master’s suspicions, and the good angel of the fags incited him to examine the freight, and, after examination, to convoy the hurdle himself up to the School-house; and the doctor, who had long had his eye on Flashman, arranged for his withdrawal next morning.

Tom Brown’s School Days was an incredibly successful work. It’s been in print consistently since the initial publication, and there have been film and TV adaptations. It was a huge hit in the US, admired by, among others President Ulysses S Grant, and Tom Hughes helped to develop a small utopian community in Tennessee based on his ideas which he named Rugby and which still exists today.

The ripples and ramifications of Arnold’s work would continue to be felt much closer to home than Tennessee however. Jumping forward into the twentieth century, in the late 1930s a young Cumbrian boy by the name of George MacDonald Fraser read Tom Brown’s School Days. Fraser loved the character of Flashman, and was deeply disappointed when he was abruptly cut from the narrative. This made a lasting impression, and 30 years later the Flashman series was born.

Fraser had a passion for reading as a child, but he was not academically gifted. His father was a doctor who wanted his son to study medicine at university. He paid for Fraser to attend grammar school (as Fraser never passed the eleven plus), but he dropped out with no qualifications. Aside from this similarity with Flashman, one can also draw connections with Fraser’s father, who also had a small role in literary history, which provides some perspective to the tone of the Flashman novels. As Fraser liked to say ‘my father buried Allan Quatermain’. The hero of H Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and its sequels, Quatermain was based on Captain Frederick Courtenay Selous a famous big game hunter, explorer and conservationist who served with the British South Africa Company in the Matabele Wars. Fraser’s father was a medical officer attached to Selous’s Legion of Frontiersman in German East Africa, modern day Tanzania, during World War One and was present when Selous was shot dead by German Colonial police in January 1917.

In regards to his own military career, service in India gave Fraser what he regarded as a privileged insight into a vanishing world. Fraser joined the army towards the end of WWII and served in the Border Regiment and the Gordon Highlanders. He was stationed first in India and saw fierce fighting against the Japanese in the latter stages of the Burma campaign. This was important to his later development of the Flashman novels as he caught a glimpse of the dying days of the British Raj. He met a ‘Punjabi princeling’ and served with soldiers who swore allegiance to the last Emperor of India George VI. India achieved independence only a few years later.

After the war, Fraser worked as a journalist back in the UK and in Canada. He eventually rose to the position of acting editor of the Glasgow Herald. About the age of forty he decided he didn’t want to be a journalist for the rest of his career and told his wife Kathleen he was going to ‘write his way out of it’. He would claim later in interviews and his memoirs that ever since reading Tom Brown’s School Days he had long pondered the question whatever happened to Flashman; and he began writing a novel structured as Flashman’s memoir. Tom Brown and Flashman are at school together during the relatively short reign of William IV so when Flashman is expelled it is right at the dawn of the Victorian age and a wealth of narrative possibility. Fraser buttressed this with an elaborate backstory, claiming in the introduction to the first novel that the Flashman papers were discovered in a sale of household furniture in Ashby de la Zouch, Leicestershire, carefully wrapped in oilskin covers and that he had been asked by Flashman’s only living relative, a Mr Paget Morrison of Durban, South Africa, to edit and arrange them for publication.

About halfway through writing the manuscript of the first novel Fraser broke his arm and couldn’t type and that brought on a period of self-doubt as to whether he should continue. It was Kathleen, a fellow journalist, who persuaded him to keep at it. She read the unfinished manuscript, and her response was to quote a line from the film Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948): ‘Boy, you don’t know the riches you’re standing on.’ Fraser finally completed the manuscript, revising as he went along (he never did a full redraft), and he estimated the entire process had taken him about ninety hours. Alas, Flashman (as the first novel was titled) was turned down by publisher after publisher for over two years before it was picked by the small firm of Herbert Jenkins and was published in 1969.

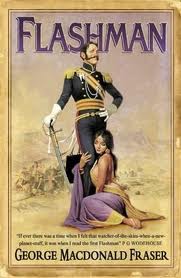

Cover artwork from the 2005 reprinting of Flashman. The background image is taken from William Barnes Wollen’s 1898 depiction of the last stand near Gandamak village during the Retreat from Kabul

The novel begins with Flashman (Fraser gave him the first name Harry which was not specified in Tom Brown’s School Days) recounting his expulsion from Rugby. He joins the 11th Regiment of Light Dragoons and is at first stationed in India and later stumbles into the Afghan mutiny. The basic premise of each novel is that despite his cowardice, through a mixture of skulduggery, cunning and sheer devil’s luck, Flashman always emerges the hero. Another feature is that Flashman is irresistible to women and has a penchant for Royal blood, some of his ‘conquests’ (or perhaps did they conquer him? Modern feminists have nothing on Victorian women) include a Maharani, Tsarina and Chinese Empress. Despite this, he has a sincere love for his wife Elspeth who, if anything, is just as adulterous as he is. Flashman recounts the disastrous Retreat from Kabul in which 4,500 British Empire troops and 12,000 civilian workers were killed in attacks led by the Afghan prince Akbar Khan. In reality, only one man survived the retreat, a surgeon by the name of William Brydon. But in the novel, Flashman survives and undeservedly becomes a hero. Over the course of the next eleven books, he would equally undeservedly accrue every conceivably honour from the San Serafino Order of Purity and Truth to the Congressional Medal of Honour, Legion D’Honneur and Knight of the Order of Bath. Aside from winning honours, Flashman also has a remarkable impact on the modern view of the Victorian age. The novels make you question your view of history and suggest that history is not made by idealistic men pursuing noble pursuits but by cockup and cowardice. For instance, Flashman inadvertently starts the Charge of the Light brigade after a heavy drinking session leaves him flatulent and frightens the horses.

Flashman runs into many historical figures in the stories, some of whose names resonate throughout history, Disraeli, Abraham Lincoln, Bismarck, General Custer, Lord Palmerston. But there are also another set of historical characters he comes across not quite as famous but equally distinctive such as Lola Montez, the actress who became the de facto ruler of Bavaria, Suleiman Usman a Borneo pirate educated at Eton, and Josiah Harlan an American adventurer who became Prince of Ghor. Harlan is a character in Flashman and the Mountain of Light (1990) set in the Punjab during the First Sikh War, he and Flashman get into a tussle over the Koh-i-Noor, one of the diamonds of Queen Victoria’s Crown Jewels. Each Flashman novel has voluminous endnotes written by Fraser to contextualise much of the history. They’re a joy to read as not only are they deeply informative, but Fraser has a dry sense of humour which contrasts with Flashman’s bawdy wit. The endnote on Josiah Harlan is particularly revealing and makes me think that Flashman is at least in part based on the characters he meets:

Josiah Harlan (1799-1871) was born in Newlin Township, Pennsylvania, the son of a merchant whose family came from County Durham. He studied medicine, sailed as a supercargo to China, and after being jilted by his American fiancée, returned to the East, serving as surgeon with the British Army in Burma. He then wandered to Afghanistan, where he embarked on that career as diplomat, spy, mercenary soldier, and double (sometimes treble) agent which so enraged Colonel Gardner. The details are confused, but it seems that Harlan, after trying to take Dost Mohammed’s throne, and capturing a fortress, fell into the hands of Runjeet Singh. The Sikh Maharaja, recognising a rascal of genius when he saw one, sent him as envoy to Dost Mohammed; Harlan travelling disguised as a dervish, was also working to Dost’s throne on behalf of Shah Sujah, the exiled Afghan king; not content with this, he ingratiated himself with Dost and became his agent in the Punjab – in effect, serving three masters against each other. Although, as one contemporary remarks with masterly understatement, Harlan’s life was now somewhat complicated, he satisfied at least two of his employers: Shah Sujah made him a Companion of the Imperial Stirrup, and Runjeet gave him the government of three provinces which he administered until, it is said, the maharaja discovered that he was running a coining plant on the pretence of studying chemistry. Even then, Runjeet continued to use him as an agent, and it was Harlan who successfully suborned the Governor of Peshawar to betray the province to the Sikhs. He then took service with Dost Mohammed (whom he had just betrayed), and was sent with an expedition against the Prince of Kunduz; it was in this campaign that the patriotic doctor “surmounted the Indian Caucasus, and unfurled my country’s banner to the breeze under a salute of 26 guns… the star-spangled banner waved gracefully among the icy peaks.” What this accomplished is unclear, but soon afterwards Harlan managed to obtain the throne of Ghor from its hereditary prince. This was in 1838; a year later he was acting as Dost’s negotiator with the British invaders at Kabul; Dost subsequently fled, and Harlan was last seen having breakfast with “Sekundar” Burnes, the British political agent.

Incidentally Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King (1888) was partly based on Harlan, and the Flashman books are full of literary references suggesting that Flashy has inadvertently inspired some of the great works of literature. Royal Flash (1970) is based on Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), and at the end of the novel Flashman describes his story to Hope in a London club. There is another wonderful endnote by Fraser about Flashman’s reading habits:

The Flashman papers abound in erratic literary allusions – the present volume contains echoes of Donne, Shakespeare, Macauley, Coleridge, Voltaire, Dickens, Scott, Congreve, Byron, Pope, Lewis Carroll, Norse mythology, and obscure corners of the Old Testament – but it would be rash to conclude that Flashman had any close acquaintance with the authors; more probably the allusions were picked up second hand from conversations and casual reading, with two exceptions. He knew Macaulay personally, and had certainly read his Lays, and he seems to have had a genuine liking for Thomas Love Peacock, whose caustic humour and strictures on whiggery, political economy, and academics probably appealed to him. For the rest, we may judge that Flashman’s frequent references to Punch, Pierce Egan’s Tom and Jerry, and sensational fiction like Varney the Vampire, more fairly reflect his literary taste; we know from an earlier volume that the word Trollope meant only one thing to him, and it was not the author.

There are also many metafictional and paratextual details. In two of the books Fraser states in the intro that the text was edited before him by Flashman’s sister-in-law Grizel de Rothschild who takes a very dim view of his choice language and blasphemy (and you can see the swear words edited on the page) so we are led to believe we are reading a manuscript with one author and two editors working generations apart. In Flashman in the Great Game (1975) Flashman actually reads a copy of Tom Brown’s School Days making him a fictional character in a novel reading a novel featuring him as a fictional character. Oddly enough, there is very little scholarship on Fraser’s work, but I can help thinking that if an author such as Paul Auster or director like David Lynch were to do something as inventive that the critics would laud it for being heavy with postmodern symbolism.

There are allusions in the Flashman novels to adventures, which were never actually published as individual books. Flashman served on both the Confederate and Union side during the American Civil War and claims to have tipped things in the North’s favour during the Battle of Gettysberg, although how he managed this he never reveals. He also makes references to being aide-de-camp to the ill-fated Emperor Maximillian I of Mexico. It’s a shame these adventures did not appear in standalone volumes, possibly because Fraser claimed he didn’t like Flashman, and he couldn’t write the novels back to back as he had to pursue other projects in between. Flashman does have his redeeming features, however: he is a skilled linguist with a fantastic memory and a skill for reportage. Although he lies frequently to save his skin, in his memoirs he assures the reader he being honest to us. The reader gets a vivid picture of life in a time and place that seem completely alien to us. In Flashman’s Lady’s (1977) Flashman is stranded in Madagascar and reluctantly becomes the lover of the tyrannical Queen Ranavalona I. He gives a scary and funny portrayal of one of the most primitive, archaic, brutal and isolated societies that existed at the time. I quote the scene where Flashman first meets Ranavalona at length because it is one of the best combinations of bawdy wit with razor-sharp reportage found in the Papers:

She paced slowly to the front of the balcony and the sycophantic mob beneath went wild, clapping and calling and stretching out their hands. Then she stepped back, the girls with the silk tent contraption carried it round her, shielding her from all curious eyes except the two that were giggling down, unsuspected, from above; I waited, breathless, and two more girls went in beside her, and slipped the cloak from her shoulders. And there she was, stark naked except for that ridiculous hat.

Well, even from above and through a muslin screen there was no doubt that she was female, and no need for stays to make the best of it, either; she stood like an ebony statue as the two wenches began to bathe her from bowls of water. Some vulgar lout grunted lasciviously, and realizing who it was I shrank back a trifle in sudden anxiety that I’d been overheard. They splashed her thoroughly, while I watched enviously, and then clapped the robe round her shoulders again. The screen was removed, and she took what looked like an invalid ebony horn from one her attendants and stepped forward to sprinkle the crowd. They fairly crowed with delight, and then she withdrew to a great shout of applause, and I scrambled down from my window thinking, by George, we’ve never seen little Vicky doing that from the balcony at Buck House – but then, she ain’t quite equipped the way this one is.

What I’d seen, you may care to know, was the public part of the annual ceremony of the Queen’s Bath. The private proceedings are less formal – although, mind you, I can speak with authority only for 1844, or as it’s doubtless known in Malagassy court circles, Flashy’s year.

The procedure is simple. Her Majesty retires to he reception room in the Silver Palace, which is the most astonishing chamber, containing as it does a gilded couch of state, gold and silver ornaments in profusion, an enormous and luxurious bed, a piano with “Selections from Scarlatti” on the music stand, and off to one side, a sunken bath lined with mother-of-pearl; there are also pictures of Napoleon’s victories round the walls, between silk curtains. There she concludes the ceremony by receiving homage from various officials, who grovel out backward, and then, with several of her maids still in attendance, turns her attention to the last item on the agenda, the foreign castaway who has been brought in for inspection, and who is standing with his bowels dissolving between two stalwart Hova guardsmen. One of her maids motion the poor fool forward, the guardsmen retire – and I tried not to tremble, took a deep breath, looked at her, and wished I hadn’t come.

She was still wearing the sugar-loaf hat, and the scarf framed features that were neither pretty nor plain. She might have been anywhere between forty and fifty, rather round-faced, with a small straight nose, a fine brow, and a short, broard-lipped mouth; her skin was jet black and plump – and then you met her eyes, and in a sudden chill rush of fear realised that all you had heard was true, and the horrors you’d seen needed no further explanation. They were small and bright and evil as a snake’s, unblinking, with a depth of cruelty and malice that was terrifying; I felt physical revulsion as I looked at them – and then, thank G-d, I had the wit to pace forward, right foot first, and hold out the two Mexican dollars in my clammy palm.

She didn’t even glance at them, and after a moment one of her girls scuttled forward and took them. I stepped back, right foot first, and waited. The eyes never wavered in their repellent stare, and so help me, I couldn’t meet them any longer. I dropped my gaze, trying feverishly to remember what Laborde had told me – oh, h–l, was she waiting for me to lick her infernal feet? I glanced down; they were hidden under her scarlet cloak; no use grubbing for ’em there. I stood, my heart thumping in the silence, noticing that the silk of her coat was wet – of course, they hadn’t dried her, and she hadn’t a stitch on underneath – my stars, but it clung to her limbs in a most fetching way. My view from on high had been obscured, of course, and I hadn’t realised how strikingly endowed was the royal personage. I followed the sleek scarlet line of her leg and rounded hip, noted the gentle curve of waist and stomach, the full-blown points outlined in silk – my goodness, though, she was wet – catch her death…

One of the female attendants gave a sudden giggle, instantly smothered – and to my stricken horror I realised that my indecently torn and ragged trousers were failing to conceal my instinctive admiration of Her Majesty’s matronly charms – oh, J—s, you’d have thought quaking fear and my perilous situation would have banished randy reaction, but love conquers all, you see, and there wasn’t a d—-d thing I could do about it. I shut my eyes and tried to think of crushed ice and vinegar, but it didn’t do the slightest good – I daren’t turn my back on royalty – had she noticed? H–l’s bells, she wasn’t blind – this was lèse-majesté of the most flagrant order – unless she took it as a compliment, which it was, ma’am, I assure you, and no disrespect intended, far from it…

I stole another look at her, my face crimson. Those awful eyes were still on mine; then, slowly, inexorably, her glance went down. Her expression didn’t change in the least, but she stirred on her couch – which did nothing to quell my ardour – and without looking away, muttered a guttural instruction to her maids. They fluttered out obediently, while I waited quaking. Suddenly she stood up, shrugged off the silk cloak, and stood there naked and glistening; I gulped and wondered if it would be tactful to make some slight advance – grabbing one of ’em, for instance… it would take both hands… better not, though; let royalty take precedence.

So I stood stock sill for a full minute, while those wicked, clammy eyes surveyed me; then she came forward and brought her face close to mine, sniffing warily like an animal and gently rubbing her nose to and fro across my cheeks and lips. Starter’s gun, thinks I; one wrench and my breeches were a rag on the floor, I hooked into her buttocks and kissed her full on the mouth – and she jerked away, spitting and pawing at her tongue, her eyes blazing, and swung a hand at my face. I was too startled to avoid the blow; it cracked on my ear – I had a vision of those boiling pits – and then the fury was dying from her eyes, to be replaced by a puzzled look. (I had no notion, you see, that kissing was unknown on Madagascar; they rub noses, like the South Sea folk.)

With its epic narratives, exotic locations, remarkable characters and thrilling set pieces the Flashman Papers would appear to be ripe for cinematic adaptation, but in fact there has only been one film made from the Flashman novels. Royal Flash, released in 1975 directed by Richard Lester from a script by Fraser and starring, in a terrible piece of miscasting, Malcolm McDowell as Flashman. It doesn’t work as a film for a number of reasons. Firstly, the film just doesn’t let you inside Flashman’s head in the same way that the first-person narration of the books does. Secondly, although the humour of the books is often broad it comes across as lewd onscreen. Finally, there’s no mechanism onscreen akin to the endnotes and appendices of the books which contextualises the history and gives another avenue of humour. I doubt there will be any more attempts to make Flashman films. When Fraser was working on the script of the James Bond film Octopussy (1983) Cubby Broccoli expressed an interest in making Flashman films but added that they would probably cost more to make than the Bond films.

Flashman’s impact on popular culture has been huge. Christopher Hitchens wrote that when the first Flashman was released in the late 1960s, it seemed wonderfully surreal that in the age of free love, hippies and and anti-Vietnam war protest here was a character seeing the most exotic sights in the age of empire, seducing Maharanis and inadvertently becoming a hero of Victorian society: ‘It somehow didn’t seem to “fit,” amid all the feverish enthusiasms of the late sixties, that one should be so thoroughly absorbed by the doings of a racist-sexist-imperialist-you-name-it military officer’. About a third of American reviewers, many of them academics, thought Flashman was a real character. One academic described the Flashman Papers as the most important literary discovery since the Boswell Papers, and Fraser said he always felt that no American university was going to give him an honorary degree because he had duped too many intellectuals. The impact of Flashman can still be felt today, either on twitter or in the fact that David Cameron was nicknamed Flashman after he told a lesbian MP to ‘calm down dear’. It led to a very funny spoof article in the Guardian written as Flashman claiming that he wanted to no association with the ‘squirt’ Cameron ‘pink cheeks, slick hair and I’d bet two shillings to the pound he’s never been further east than Calais’, but wouldn’t mind being compared to the Right Honourable Gideon George Osborne. Fraser wrote a few books connected to the series, Black Ajax (1997) is set in Regency England and features Flashman’s father, a hero of the Napoleonic Wars and Mr American (1980) is a novel set in England from 1909 and to 1914 featuring Flashman, now in his nineties, as a supporting character. The novels ends with the outbreak of the First World War and Flashman’s observations are quite interesting in centenary year, especially when we consider modern wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

You think if we can keep Belgium green, or whatever colour it is, instead of Prussian blue, then hurrah for everyone. But war ain’t between coloured blobs – it’s between people. You know what people are, I suppose? – chaps in trousers and women in skirts, and kids in small clothes.” The General took a pull at his wine and grimaced. “I wish to God that someone would tell the Hungarians that their wine would be greatly improved if they didn’t eat the grapes first. Anyway, imagine yourself a Belgian – in Liege, say. Along come the Prussians, and invade you. What about it? – a few cars commandeered, a shop or two looted, half a dozen girls knocked up, a provost marshall installed, and the storm’s passed. Fierce fighting with the Frogs, who squeal like hell because Britain refuses to help, the Germans reach Paris, peace concluded, and that’s that. And there you are, getting on with your garden in Liege. But –“ the General wagged a bony finger. “Suppose Britain helps – sends forces to aid little Belgium – and the Frogs – against the Teuton horde? What then? Belgian resistance is stiffened, the Frogs manage to stop the invaders, a hell of a war is waged all over Belgium and north-east France, and after God knows how much slaughter and destruction the Germans are beat – or not, as the case may be. How’s Liege doing? I’ll tell you it’s a bloody shambles. You’re lying mangled in your cabbage patch, your wife’s had her legs blown off, your daughters have been raped, and your house is a mass of rubble. You’re a lot better off for British intervention, ain’t you?”

Fraser was personally opposed to the War Against Terrorism. Although he advocated helping the US through intelligence sharing, he was appalled to see British troops deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. What he would have made of the present crisis we can only guess. His pacifist streak was derived from his experiences as a soldier. Unlike Flashman, there was nothing affected about his heroism. I’d recommend his memoir Quartered Safe Out Here (1992) of his time fighting the Japanese in Burma. But he was more than a good soldier and sage commentator on the futility of modern warfare: he built his writing career, despite having no educational qualifications, to become through the Flashman novels one of the foremost experts on the Victorian era. History is never dull in the Flashman Papers.

PS. I’ll be taking a break from the blog to focus on work and take a short holiday. I hope to read James Ellroy’s Perfidia and Mike Ripley’s Mr Campion’s Farewell while basking in the Mediterranean sun. I’ll blog about both in late September.

“The basic premise of each novel is that despite his cowardice, through a mixture of skulduggery, cunning and sheer devil’s luck, Flashman always emerges the hero. ” This is the same premise as Arthur Conan Doyle’s character Brigadier Gerard. Of course, A. C. Doyle’s most famous character, Sherlock Holmes, meets Flashman in “Flashman and the Tiger”.

Hi Gary,

Yes, he meets Flashman, so to speak, and arrives at a convoluted, intellectually complex and completely hilariously wrong judgment about Flashman’s identity.

Aye, well, I’ve written the first Flashman civil war novel and am 1/3rd through the second. Unfortunately GMF’s estate won’t allow publication.

Dear Des,

Good to hear from you. Do GMF’s estate have someone in mind they want to write the missing packets or are they just being protective of the Flashman name?

Long time ago, but first time I’ve seen your question, so if you’re still ‘listening’ it’s because his estate won’t allow it.

– should have added protecting his legacy – nothing lined up.

Seems harsh. Especially as the Thomas Flashman spinoffs are available on amaon.

Surely they can see the advantage(financial ?) to continuing the series? Ian Fleming and Robert Ludlum have both been writing from the grave for years.

The MacDonald estate, having total control over publication of anything Flashman based , could/should think of authorising the missing years.

I for one, want to know what Flashman was doing on Jefferson Davis’ roof.

I found your site from a link from another authors site- writing a bio of John Charity Spring (same problem with GMF estate)

History should not be supressed! We want more!

Hi Alex, funnily enough since I wrote this piece I’ve noticed a lot of Flashman fan fiction popping up on the internet. The MacDonald estate can’t sue every fan who decides to have a crack at writing a Flashman story but if they want an official volume to fill in gaps in Flashy’s bio they should hire an established writer. Trouble is, who’d be up to the job. MacDonald Fraser is a tough act to follow.