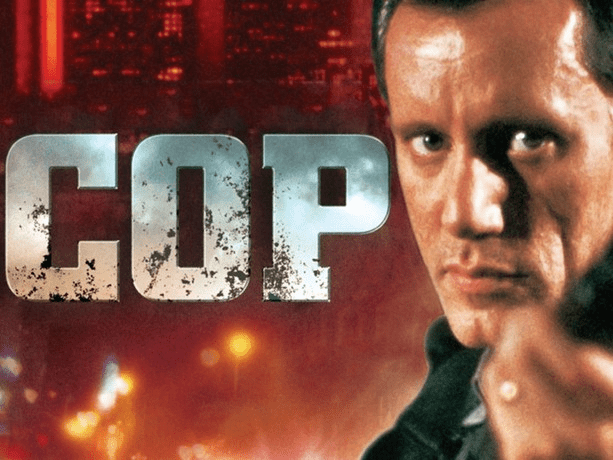

In Film We Trust – Cop

It was my pleasure to be a guest on the superlative In Film We Trust podcast to talk about Cop, the very first film adaptation of a James Ellroy novel. We had a blast discussing the somewhat underrated film, and I gave some anecdotes from my James Ellroy biography Love Me Fierce in Danger. I’ll be back on the show soon for two more episodes to discuss LA Confidential and The Black Dahlia, so stay tuned.

You can listen to the podcast here: https://creators.spotify.com/pod/show/ifwtpod

Ellroy Reads – In a Lonely Place by Dorothy B. Hughes

In the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I discuss Dorothy B. Hughes classic novel In a Lonely Place. I compare the novel to the very different, but equally acclaimed, film noir adaptation starring Humphrey Bogart. There’s also some inside information on the remake James Ellroy planned with Dana Delany.

Off the record, on the QT and very Hush Hush…

Ellroy Reads – Strega by Andrew Vachss

For the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I review Strega by Andrew Vachss. I share some of my memories of meeting Vachss, as well as giving some insight into how Vachss and Ellroy came to be published by Alfred A. Knopf.

Enjoy the episode, and make sure you take heed from the important message from the show’s sponsor at the beginning…

Mr Campion’s Christmas by Mike Ripley – Review

Albert Campion had planned on a quiet Christmas to end 1962. Snowed in with family at his remote farmhouse Carterers in Norfolk, Campion thought he was blissfully cut-off from the rest of the world until a charabanc of pilgrims arrive and the ageing toff finds himself playing host to a ragtag bunch of eccentrics. The travellers destination is nominally the Shrine of Our Lady in nearby Walsingham but Campion soon discovers his uninvited guests have more than a few secrets between them, and one them goes straight to the heart of the Cold War. Whoever said life in East Anglia was dull?

Mike Ripley has done sterling work with his Campion continuation series, keeping the spirit of Margery Allingham’s character alive while adding a new sense of style and his distinctly mischievous sense of humour. The good news is that Mr Campion’s Christmas does not disappoint. And the bad news? This is the last book in the series. Ripley is not going to write any more Campion novels for love or money, but he has ended the series in fine form and this addition should also persuade readers to explore other chapters in the life of the gentleman detective.

ELLROY READS – Laura by Vera Caspary

For the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I look at Vera Caspary’s classic novel Laura, the exemplary film noir adaptation it inspired, and how both the novel and film inspired James Ellroy’s abortive plans for a remake.

I hope you enjoy the episode. As always dear viewer, let me know your thoughts.

Hardboiled Screen: James M. Cain on Film

James M. Cain is one of the most influential writers of hardboiled crime fiction in history, but his influence on film is equally as important. Andy Rohmer has set about the gargantuan task of giving a comprehensive overview of every Cain adaptation on film, not to mention every screenplay that Cain himself ever worked on.

Most of us will have either seen or heard of the famous adaptations of Double Indemnity, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Mildred Pierce. Rohmer gives these classics the critical analysis and insight they deserve. However, I’d put money on the fact that you haven’t seen Sari Bela, a Turkish adaptation of Postman, or Yu Hai Qing Mo a Hong Kong adaptation of Mildred Pierce. And I’d bet the bank that you haven’t seen Eruption, a hardcore porn adaptation of Double Indemnity starring Johnny Wad, the adult actor who will forever be remembered for his involvement in the Wonderland murders. Well, maybe you have seen Eruption but you’re disinclined to admit it.

Andy Rohmer has hunted down all of these films and he gives them a fair hearing. Needless to say, some of them are awful but he finds hidden gems and fine examples of World Cinema that Cain’s writing has inspired. Rohmer gives the reader insightful analysis and catty behind the scenes gossip with the ready wit he displayed in previous volumes of his Writers-On-Film series.

Order a copy today. It’s a terrific read that will make you raise a whiskey tumbler to Cain’s incredible contribution to literature and film.

Highbrow Lowbrow: Halloween Special

Highbrow Lowbrow returns with a Halloween Special. My pick for this episode is Ken Russell’s colourfully bonkers adaptation of The Lair of the White Worm, and my podcast co-host Dan Slattery plumps for the classic BBC hoax Ghostwatch.

We’ve picked two British classics which, we suspect, are less well-known to our predominantly American audience. We hope they give you some spinetingling fun this All Hallows’ Eve.

You can listen to the episode here.

I would like to share with my readers a special moment. This was the nerve-wracking but ultimately joyous moment when my biography of James Ellroy, Love Me Fierce in Danger, was announced as the winner of the Edgar Award for Best Biographical/Critical Book at the Edgar Awards held at the Marriott Maquis Hotel in New York City in May.

Thank you to everyone who subscribes and supports this site, as well as to everyone who has read and reviewed the book. Your support continues to be invaluable.

The full ceremony is below, but you can watch my watch my acceptance speech here.

ELLROY READS – Luther by John Osborne

For the latest episode of Ellroy Reads I look at John Osborne’s play Luther. This has to be one most unique texts I have covered on the show as it not a hardboiled or noir narrative in any way. Rather, it is a text that has inspired Ellroy’s Christian faith, and yet Osborne, the heavy-drinking womanising English playwright, is no one’s idea of an evangelist.

Watch me try to get to the bottom of this mystery in the video below, and do consider subscribing, liking, commenting and sharing. It helps me to keep the faith: