A James Ellroy Playlist: Obsession

‘Since I Don’t Have You’ is one of James Ellroy’s greatest short stories. Turner “Buzz” Meeks is hired by Howard Hughes to locate one of his favourite “actresses” (a polite euphemism for Casting Couch victim). Her name is Gretchen Rae Shoftel. Hughes has lost track of her and is suffering from a severe case of absence makes the heart grow fonder. Things get complicated when Meeks is also hired by Mickey Cohen to find Gretchen. Cohen had a one night stand with Gretchen and has grown obsessed with her since she disappeared. Another associate of Meeks is RKO Film Producer Sid Weinberg. Weinberg is described as a ‘Filthy rich purveyor of monster cheapies’. He completes the trinity of men obsessed with women who have vanished, ‘he was known to be in love with a dazzling blonde starlet named Glenda Jensen, who hotfooted it off into the sunset, never to be seen again’. Meeks notes that Glenda ‘looked suspiciously like (Gretchen)’. Meeks locates the troubled Gretchen, and in order to keep her out of the clutches of Hughes and Cohen he introduces her to Sid Weinberg, and the actress and producer begin a happy partnership making ultra-cheap but profitable films together.

Gilda, Amado Mio

In his study of Ellroy, Peter Wolfe notes that a ‘possible source for Glenda’s name is the title character of the 1946 movie, Gilda, played by redhaired Rita Hayworth, whose income taxes Ellroy’s father prepared.’ Glenda Jensen may be a forerunner to Glenda Bledsoe in Ellroy’s White Jazz, who is also an actress Howard Hughes is trying to obtain information on. It’s worth noting that Ellroy often loosely based his female characters on his partners, and The Big Nowhere was dedicated to a woman named Glenda he was in a relationship with at the time. However, in White Jazz there is a reference to Gilda which suggests the film may have been a source of inspiration to the author. Lieutenant Dave Klein is reading a file on a suspect who is a paedophile named ‘Rita Hayworth’

‘Panty sniffers, sink shitters, masturbators – lingerie jackoffs only. Faggot burglars, transvestite break-ins, ‘Rita Hayworth’ – Gilda gown, dyed bush hair, caught blowing a chloroformed toddler. The right age – but a jocker cut his dick off, he killed himself, a full-drag San Quentin burial.’

In the film Gilda, the titular character performs two songs. The most famous is “Put the Blame on Mame”, a sexy number in which she wears the ‘Gilda gown’, a strapless black dress which helped to cement the image of the femme fatale. All of Hayworth’s singing in Gilda was dubbed by Anita Ellis. The more tender love song is “Amado Mio”, in which the dubbed Hayworth gets to showcase her dancing which was how her career began as a member of “The Dancing Cansinos”.

In “Since I Don’t Have You”:

Gretch also starred in the only Sid Weinberg vehicle ever to lose money, a tear jerker called Glenda about a movie producer who falls in love with a starlet who disappears off the face of the earth. The critical consensus was that Gretchen Rae Shoftel was a lousy actress, but had great lungs. Howard Hughes was rumoured to have seen the movie over a hundred times.

Since I Don’t Have You

Rewatching a film endlessly isn’t the only manifestation of Howard Hughes’s obsession. Meeks narrates:

A biography I read said that he (Hughes) carried a torch for the blonde whore straight off into the deep end. He’d spend hours at the Bel Air Hotel looking at her picture, playing a torchy rendition of “Since I Don’t Have You” over and over.

“Since I Don’t Have You” was a hit for The Skyliners in 1958. It has been covered many times since, and one might argue that by adopting the title and its pining for lost love themes Ellroy has covered it himself. There are chronology issues here. Ellroy’s “Since I Don’t Have You” is set in the 1949, and in LA Confidential Meeks is killed by Dudley Smith in February 1951. But the Meeks of this short story is an old man, perhaps a little ghostly, and is prone to some pining himself, ‘I miss Howard and Mickey, and writing this story has only made it worse.’

Below is a video of The Skyliners performing “Since I Don’t Have You”. The choreography isn’t great, but there’s something about its cheap B-Movie Western look that makes me a little nostalgic. It strikes me as something Sid Weinberg would produce starring his beloved Glenda.

Listen to this song and pine for your own Glenda/Gilda/Gretchen:

Highbrow Lowbrow: Licence to Kill vs Moonraker

The latest episode of Highbrow Lowbrow is a James Bond-themed special. My podcast co-host Dan Slattery and I have always loved debating the pros and cons of the different eras of the James Bond film series and the actors who have portrayed 007. In this episode, Dan defends Timothy Dalton’s gritty, serious performance as Bond in Licence to Kill. Whereas I argue for Roger Moore’s lighter more comedic approach in Moonraker.

Hope you enjoy listening, and let us know where you stand on the great Bond debate.

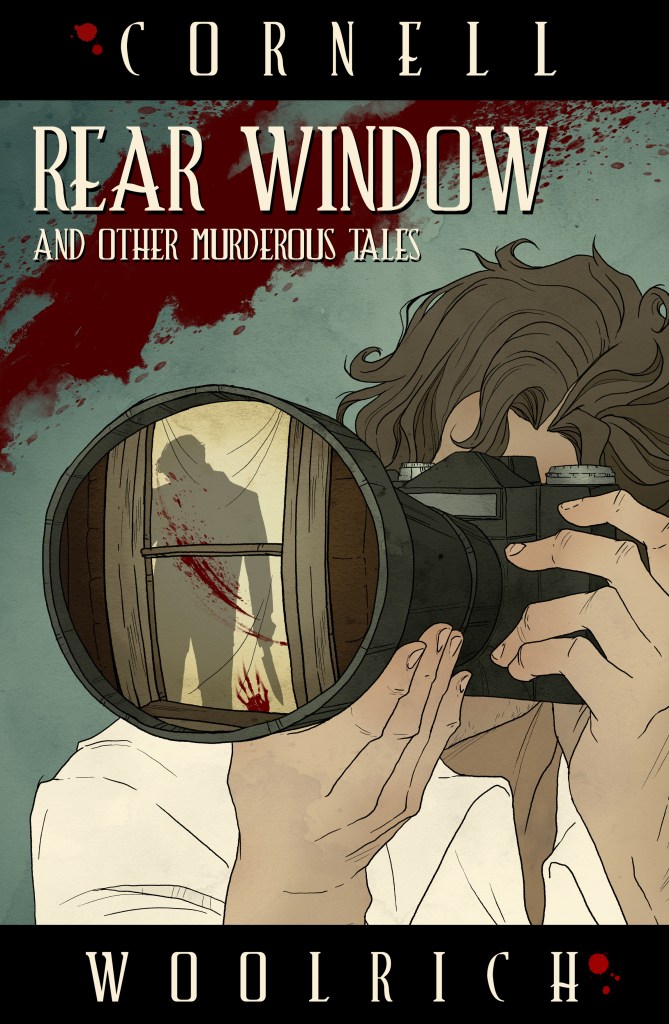

Rear Window by Cornell Woolrich Lives Again

The following post is written by guest author Jacklyn Saferstein-Hansen. Jacklyn Saferstein-Hansen is an agent at Renaissance Literary & Talent, the agency that represents Cornell Woolrich’s literary estate. She personally curates these brand new Woolrich collections in an effort to revitalize his work.

Rear Window. The title conjures the names Alfred Hitchcock, James Stewart, Grace

Kelly. But few know the writer to whom the 1954 film’s underlying story is attributed: Cornell

Woolrich.

One of the most famed crime and suspense writers of the 20th century, Woolrich penned

more than two dozen novels and over two hundred novellas and short stories throughout his

lifetime. Though his first suspense novel, The Bride Wore Black, published in 1940 to critical

acclaim, is perhaps his most renowned work, no Woolrich tale has had more prolonged success

and recognition than the short story “Rear Window.” Submitted to his editor under the title

“Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint,” it was published in 1942 under the name “It Had to be

Murder,” a much snappier and more fitting title for Dime Detective, the pulp magazine in which

it appeared. The name changed again when, two years later, the story appeared as “Rear

Window” in the 1944 fiction collection After-Dinner Story, and that’s the name that stuck. A

decade later, Hitchcock adapted it into the wildly successful thriller film whose nerve-shredding

sequences and questions of voyeurism still resonate today. The film is a marvelous adaptation of

the source material, but Woolrich’s original story offers a magic all its own that is best

experienced on the page.

For the first time in years, “Rear Window” helms a brand new short fiction collection,

this one with a murderous bent. Rear Window and Other Murderous Tales features eight more of

Woolrich’s best suspense tales, stories that “Rear Window” has never appeared with in previous

collections put out by other publishers. Many of these stories have not been in print for several

decades, so this collection will come as a treat for those looking to discover new Woolrich tales.

Each story within Rear Window and Other Murderous Tales has a murder at its center. The

reader experiences the psychological repercussions of this most gruesome crime through a

variety of perspectives: the murderer himself, the investigating detective, a witness, an amateur

sleuth, the falsely accused, and an innocent spouse. This is Woolrich at his best, using the

unspeakable act of murder to drive his characters to desperate ends in an unflinching

examination of human nature.

This new collection has just been released by Villa Romana Books, the publishing arm of Renaissance Literary & Talent, the agency that represents the various parties who control Woolrich’s literary estate. They’ve been nearly as prolific as Woolrich himself, recently putting out eight other fantastic volumes of his short fiction, creatively curated by theme: Women in Noir (three volumes), An Obsession with Death and Dying (two volumes), and Literary Noir: A Series of Suspense (three volumes). It’s thanks to the Renaissance team that Woolrich’s work lives again. They’ve sorted out complicated rights issues to the hundreds of stories and dozens of novels he wrote, and have pored through the canon to create these brand new collections for crime, suspense and noir fiction fans old and new. Renaissance’s robust ebook and paperback publishing platform has made available a vast array of Woolrich’s work, individually as well as in collections, and it is not to be missed. Gorgeous cover illustrations by talented artist Abigail Larson breathe colorful new life into each edition.

Rear Window and Other Murderous Tales, along with many other Woolrich works, is

available on Amazon in both ebook and paperback.

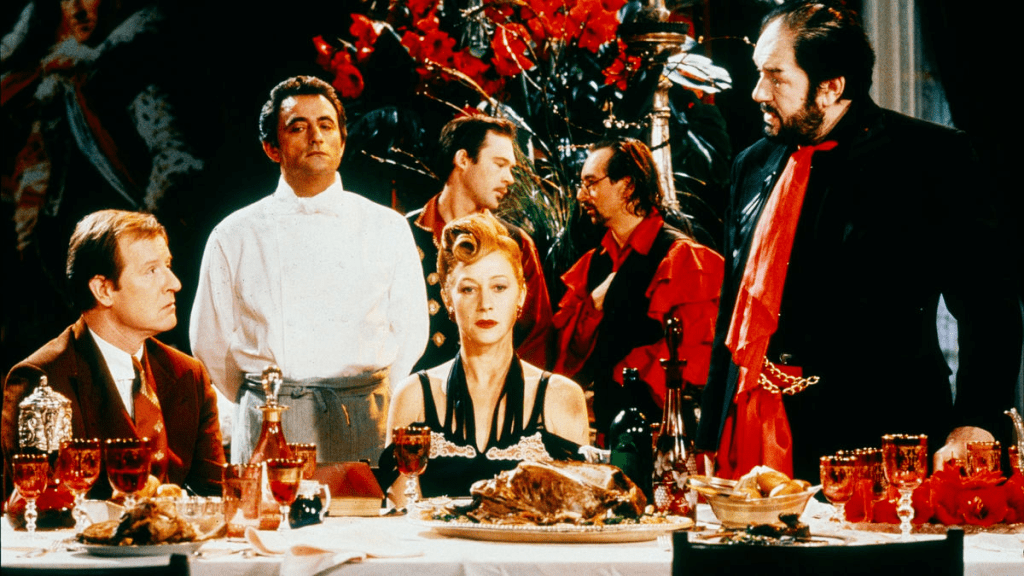

Highbrow Lowbrow Episode 3

The latest episode of Highbrow Lowbrow is now available. The theme is Eighties classics. My co-host, Dan Slattery, defends Electric Dreams and I argue the merits of The Cook, The Thief, His Wife & Her Lover.

Sadly, only hours after we had recorded the episode it was reported in the press that Electric Dreams star Lenny Von Dohlen had died.

You can listen to the full episode here.

James Ellroy’s Hollywood Death Trip

The long-awaited podcast James Ellroy’s Hollywood Death Trip is now available on Audible. Here’s some more information about the series on Ellroy’s website. If you enjoy this series you may be delighted to hear that Audio Up are also producing a 12 episode podcast adaptation of American Tabloid. There have been many attempts to adapt American Tabloid over the years. It seems Audio Up have succeeded where Hollywood and the TV studios have failed.

Jill Dearman: Interview with the Author of JAZZED

Jazzed is the compelling new novel by Jill Dearman. It delivers an ingenious twist on the Leopold & Loeb case – what if the two killers were women? The setting is Barnard College for Women, New York City, in the 1920s. Wilhelmina ‘Will’ Reinhardt and Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Raab are Freshman roommates at Barnard. Like many people who are attracted to each other, Will and Dolly have an interesting combination of similarities and differences. They are both from upper middle class Jewish families. However, Will is bookish and shy whereas Dolly is dominant, confident and knows exactly how to tease Will by withholding affection. At first their relationship blossoms among the Harlem speakeasies that made New York the epicentre of the Jazz Age. But an interest in Nietzschean philosophy thrusts the two women into increasingly transgressive acts that will ultimately lead to their destruction. When, for reasons of barely concealed prejudice, Barnard officials pair the couple off with new roommates, Dolly decides that she and Will must break the ultimate taboo by committing, and getting away with, the perfect crime – kidnapping and murdering a child.

Anyone who is interested in the Leopold & Loeb case, or indeed any reader who broadly enjoys crime fiction, will find Jazzed riveting. This is a story which is by turns sexy, dark, disturbing and tragic and yet it all coheres seamlessly into an exhilarating read.

I’ve been corresponding with Jill for several years now as we are both fascinated with True Crime, Film Noir and James Ellroy. Every conversation with Jill is a joy. She has wit, verve and joie de vivre. Enjoy this interview and buy yourself a copy of Jazzed. It’s sizzling.

Interviewer: How did you become interested in the Leopold and Loeb case?

My late father, a New York City cab driver, was obsessed with true crime and introduced me to the case when I was an adolescent. There was something about the relationship between the two boys that resonated for me. I wondered how much the “madness” of desire and the hatred (by the mainstream) of that desire might be the spark that ignites the “need” to kill. If your very being – who you are as a person – is completely oppressed, and you are being kept from the one you love, wouldn’t you feel desperate? I believe my father had a lot of desperate drives and I explore some of the backstory of our relationship in this personal essay, “Compulsion.”

Interviewer: Was it difficult to transfer/adapt the personalities of two male killers into the personalities of Dolly and Will?

No! They poured out of me, as if Dolly and Will were waiting for a chance to come to life. Though Dolly was based on Loeb, and Will on Leopold, their inner lives were their own. As I wrote and revised it was clear that being women informed so much of their experience.

Interviewer: Have you always been fascinated by the Jazz Age, and how would you describe its legacy in America today?

No, I came to jazz later. I had recently picked up piano and developed an immediate love for improvisation, just a year before penning my writing book, Bang the Keys. There is something about jazz that is so deliriously uninhibited. Whether listening to jazz or reading a novel, that sense of music or prose being created in real time, through the art of improvisation, is just so thrilling. And I am endlessly fascinated by the way jazz stands as “America’s music.” I think all of the United States is one big improvisation. Unlike older culture, the United States seems to get by on fast talk and a strange lack of history, of groundedness. Jazz stands as a perfect model of America’s selective memory. We’re a country built on superconfidence and a predilection for hucksterism.

The swagger and bravado of jazz captures those vibes. And at the same time Jazz emerged from Black culture and was commodified by whites. This particular early ‘20s era of jazz that serves as a character in my book is of special fascination to me. All the lesbian jazz singers, the Black jazz acts that rose up from the underground against the odds; there was a sense of rebellion. By the Great Depression just five years later, the mood would change.

I’m reminded of the Obama years in the United States. It seemed like this country might just move towards a new time of personal freedom. A Black president. Gay marriage. Trans identity going mainstream. There was a terrific prestige television show that aired during Obama’s second term called Treme. David Simon of The Wire fame was one of the creators. Treme dealt with the jazz life in New Orleans, just after Hurricane Katrina. The sense of life and the sense of doom merge perfectly. Given the dark path America is taking, it’s a great time to revisit the Jazz age and compare notes from a 100 years ago.

Interviewer: You’ve experimented with a variety of styles with Jazzed and your previous novel The Great Bravura. How would you describe the difference in both style and narrative between the two novels?

Well, The Great Bravura was much more stylized noir, whereas Jazzed is more direct in terms of language. In Bravura, which was set in 1948, it was fun to use some surreal techniques, such as making gay marriage just a regular part of life. Given the state of the world today, that seems even more surreal! And since the novel revolves around magic, I felt compelled to explore not just the work-a-day world of a magician, but also elements of mysticism, and the unknown. Jazzed is realist in its narrative style, but the key plot element of music allows the characters to experience a kind of transcendence, universal love. And musicality is of great importance to me in my writing, so I really do try and “hear” books as I compose them.

Interviewer: The novel provides an important critique of sexism, racism and homophobia. How did you approach this when your two main characters commit the worst crime of all, so in theory they shouldn’t be sympathetic?

It’s interesting because we are living in a moment and in a world in which the interconnectedness among us is hard to miss. The book is set about a hundred years ago, before “intersectionality” was termed and before the Internet and the climate crisis allowed us to see with such immediacy how connected and interdependent we all are. What I wanted to do with Will and Dolly was show that they were influenced by the many forms of oppression they faced. To quote the Bruce Springsteen song, “Johnny 99”: “Now I ain’t saying that makes me an innocent man, but it was more than all this that put that gun in my hand.”

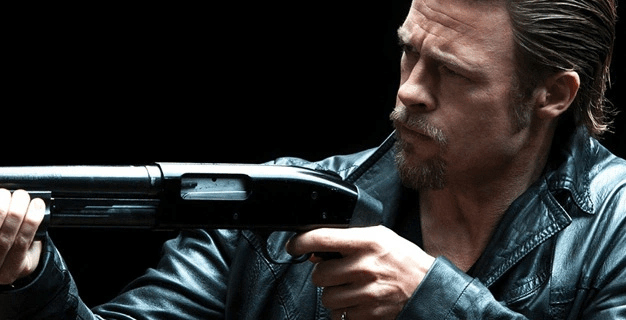

Highbrow Lowbrow: Episode Two

The second episode of Highbrow Lowbrow is now available. In this episode I discuss the neo-noir Killing Them Softly and my podcast co-host Dan Slattery defends the action thriller Taken 3. You can listen to it here. Enjoy!

Gods of Deception is the brilliant new work of historical fiction by David Adams Cleveland, who takes the reader on an epic, revisionist sweep through post-war American history. The nonagenarian Judge Edward Dimock is writing his memoirs. The most troubling episode is his role as the defence attorney to Alger Hiss in the ‘trial of the century’. Dimock’s conscience is stricken at the thought that Hiss could have been guilty of espionage. Dimock enlists his grandson, Princeton astrophysicist George Altmann, to research the case. It’s the beginning of an investigation that could change their understanding of America’s Cold War history.

David Adams Cleveland is a novelist, historian and former correspondent and arts editor for Voice of America. I had the pleasure of talking to him about Gods of Deception. Interviewing David is a joy. It’s like sitting back with a snifter of brandy and listening to Gore Vidal or E.L. Doctorow wax lyrical about American history. Enjoy the interview and buy the book.

Interviewer: What motivated you to write Gods of Deception?

I found the Alger Hiss spy trial—the “trial of the century” as it was known, to be fascinating on many levels, especially for a fictional treatment. In Alger Hiss (and we now know for a certainty that he was guilty of spying) you have a spy’s spy who never, to his dying day, admitted his guilt, even in the face of overwhelming evidence. In this, he was very unlike the infamous British spies, the Cambridge Spies: Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, and Kim Philby who were plagued by fear of exposure and so escaped to the Soviet Union where they died early of alcoholism in their Moscow dachas. Hiss maintained his equanimity to the end, refuting his accusers and seeking redemption.

Equally mesmerizing was the clash of Hiss and his accuser and one-time GRU (Soviet military intelligence) handler, Whittaker Chambers, who testified in intimate and telling detail about his days photographing top secret State Department documents passed to him by Hiss, many copied by his wife, Priscilla Hiss, on their Underwood typewriter. In the trial and later in his memoir, Witness, Chambers wrote at length about their relationship—everything from trade craft, to renting summer homes together, to rearing their children and bird watching. And yet Alger and Priscilla Hiss denied everything, only admitting that they might have known Chambers under a different name and for a very short time. These clashing stories—parallel universes in which both parties claimed to be telling the truth, were catnip for a writer trying to sort fact from fiction.

And then there is the astonishing way the guilty verdict returned against Hiss divided the country for almost five decades. Half believed vehemently in his innocence, that he was framed by Whittaker Chambers and the FBI and perhaps Richard Nixon as well; the other half believing he was a spy and a traitor. How could opinion be so drastically divided? For some, the elegant well-spoken Alger Hiss represented the ideals of the Eastern establishment and Roosevelt’s New Deal, and so the accusations levelled against him seemed an attack on the very foundations of liberalism. While his accuser, Whitaker Chambers, an admitted ex-communist and spy, was, oddly enough, seen by those of more conservative views as a soul who had confessed his sins and so offered witness to the dark underside of socialism in the guise of Stalin and the totalitarian state. As a subject of fiction such competing world views and how they played out in three generations of one family seemed a perfect opportunity to explore the mystery of how humans are drawn to various ideological viewpoints and often dragged down by a misbegotten allegiance.

Interviewer: Our understanding of the Alger Hiss case has changed with time. By telling the story across three generations of the same family do you find it easier to portray the complexity of that change?

What changed over the decades since Hiss’s conviction in 1950 was the very slow accumulation of new evidence confirming Hiss’s guilt along with changes in attitudes toward Stalin and the Soviet Union. These shifts certainly lent themselves to fictional exploration over three—actually, four generations of the Dimock family. Even during the two trials (the first ending in a hung jury) these tectonic shifts in public opinion were taking place with the imposition in Eastern Europe of the Iron Curtain and the test of a Soviet atom bomb in August of 1949, followed by the outbreak of the Korean War and the Soviet invasion of Hungry in 1956 and Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s crimes. Support for the Soviet experiment and the American Communist Party (numbering 200,000 at its height) declined rapidly. And with it an uneasiness among the far-left supporters of Hiss and the possibility that he may indeed have flirted with the communist party or worse. The most damning evidence of Hiss’s guilt didn’t come out until the mid-90s with the release of the Venona decrypts of Soviet cable traffic from the 1940s, and the brief opening of Soviet intelligence files during the Boris Yeltsin presidency of Russia. The cumulative evidence was damning. Not only was Alger Hiss a spy but an agent of influence who sat at Roosevelt’s right hand at Yalta, where he was debriefed each morning by his Soviet handler—giving away the US and Allied negotiating position. Hiss and his fellow spies in the White House, Lauchlin Currie, and Treasury, Harry Dexter White, had done Stalin’s bidding throughout the war years and beyond. On his way back from Yalta, Hiss and members of the Yalta delegation stopped in Moscow, where Hiss was taken aside in a secret ceremony and given the Order of the Red Star for his service to the Soviet Union.

I designed my narrative to flesh out this often-complex changing perspective on Alger Hiss by having my lead protagonist, George Altmann, a Princeton astrophysicist, explore the Hiss affair by questioning his grandfather, “the Judge”, who had been on Hiss’s defense team. Through George’s eyes, and his grandfather’s memoir, along with the Judges three daughters, the reader becomes aware of how attitudes towards Alger Hiss have evolved over time, a changing picture that is reflected not just in the characters’ lives but that of the country as well.

Interviewer: The novel implies Soviet penetration of the US government at the highest level which affects key events in American history. Did your research into the case inform this narrative approach?

When I began my research on the Alger Hiss case, I assumed that Hiss was probably guilty as spelled out in his perjury conviction: passing top secret State Department documents to his GRU (Soviet military intelligence) handler, Whittaker Chambers, in the late thirties. I was stunned to find that the real damage Hiss and his confederates did was as agents of influence, along with close to 500 of Stalin’s willing spies who infiltrated the US government and related war industries. We now know that Harry Dexter White, an undersecretary at Treasury, did Stalin’s bidding by pushing for harder and harder sanctions on the Japanese in 1941—Operation Snow, in hopes of provoking the Japanese to attack south into the Pacific rather than continuing to attack Soviet positions in northeastern Asia along the border of Mongolia and Siberia. Pearl Harbor was the result.

Another Soviet agent in army intelligence, William Weisband, tipped off his KGB handler that the US had broken Soviet military logistic codes, at which point the Soviet military changed their codes, so leaving the US in the dark as Stalin shipped war materials to North Korea. If Truman’s White House had been able to monitor this movement of supplies, tipping off the US about the buildup for a North Korean attack, the US might well have been able to warn off Stalin and prevent the invasion of South Korea and the Korean War. Of course, the story of the Rosenbergs and how their ring of spies stole US atomic bomb secrets is well known. But I speculate in the novel, based on my research for Gods of Deception, that Soviet fears that their technical spy networks might be compromised and uncovered caused them to do everything in their power to prevent Alger Hiss’s conviction, which they feared, as indeed was the case, would open a Pandora’s box of spy fever, and so endanger their ongoing operations to steal details about the hydrogen bomb, then in development. There were a number of unexplained deaths and disappearances of potential witnesses in the Hiss spy case, ambiguous falls from buildings (a KGB specialty), or exile behind the Iron Curtain, much remarked on at the time, which I have explored in Gods of Deception. A title that references the fervent self-image of many American followers of Lenin and Stalin who saw themselves in the vanguard of history.

The 1950 conviction of Alger Hiss for perjury, even if only for passing top secrets documents to the Soviets in the late thirties, alerted the country that they had a very real problem with Stalin’s KGB and GRU spy networks. The great irony is that by the time this had all sunk in with what is now known as the “Fifties Red Scare”, most of the damage was long done and Stalin’s spies had either been exposed or had slunk away never to be heard from again.

Interviewer: Tell us a little about your journalistic background. How did your experiences inform the writing of Gods of Deception?

My years working for Voice of America covering the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and China during the perestroika-glasnost period left me with a pretty good understanding of how totalitarian regimes employ the big lie and disinformation to hold their societies in check, while falling back on force and repression when all else fails. This made the Alger Hiss case all the more problematic for me: how was it that at least 500 other Americans were so willing to do Stalin’s bidding (they were not paid but were eager supplicants). Not to mention the 200,000 members of the American Communist Party, which served as a recruiting ground and underground infrastructure for these spies and their handlers. Except for Whittaker Chambers’ autobiography, Witness, and a few other spy memoirs very little about these people and why they chose a path of subversion has surfaced, even seventy years later. This seemed inviting territory for a fictional exploration of the motivations of these American spies, the compromises they made, the lies they lived, and the pain and loss bequeathed to their families.

Interviewer: With Putin fighting a hopefully unwinnable war against Ukraine, what happens next in the US’s relationship with Russia? Is a military confrontation between Nato and Russia inevitable?

It has been eerily strange for me to have Gods of Deception come out with the onset of Putin’s war against Ukraine—Dracula pulling out a silver stake and walking the earth again. Everyone thought that Putin, trained in the dark arts of the KGB, could not reconstitute the terrifying days of Stalin’s Soviet Union with its use of the “big lie” and false flags, repression backed by brutal force, and—even with the internet, imposing state sponsored propaganda to mold public opinion. It looks like Putin has managed to bring down another Iron Curtain—if not another Cold War, at least for a time, possibly a fleeting moment in the great sweep of history, but a moment for which the Ukrainian people are paying so dearly.

I’m hopeful that the Russian people will soon realize that Putin is a tyrant intent on bringing about another dark age in Russia, and so find a way to replace him and his circle of aging ex-KGB sycophants. Putin’s military is looking more and more inept even as they inflict horrific suffering and destruction. So, I don’t see the war in Ukraine spreading any wider, especially since recent advancements in military technology now seems to favor the defense. Sad to say, when I started Gods of Deception it seemed a story about a distant past—now, suddenly, a cautionary tale for our times.

Gods of Deception is published by Greenleaf Book Group

A James Ellroy Playlist: The Beat Poets

James Ellroy’s LA Quartet is set predominantly in the 1950s and the influence of jazz and film noir on Ellroy’s narratives is fitting given the cultural trends of the decade. But just as the 1950s was the apex of the film noir age, many other genres and art forms were thriving. The Western, Musical, Swashbuckler and Biblical epic all enjoyed their heyday during the 50s.

In this article I am going to explore a lesser-known cultural influences on Ellroy’s work – beat poetry. The Beat movement was peaking during Ellroy’s childhood and had an inevitable impact on him.

High School Drag

Given Ellroy’s conservative views, it’s not surprising that even as a child he associated Beat Poetry with the derogatory term Beatnik. The Beatnik was a media stereotype which portrayed the Beat Generation as a motley crew of drug addicts, criminals and hilariously pretentious artists.

High School Confidential was the first film Ellroy saw at the cinema after the murder of his mother – Jean Ellroy. It’s not surprising, given the timing, that it had a profound effect on the young Ellroy. Produced by legendary schlockmeister Albert Zugsmith, the film is nominally a crime story. A police officer poses as a student to go undercover in a high school and bust a narcotics ring run by the enigmatic ‘Mr A’. However, the film is too consistently outrageous for the crime narrative to be taken seriously, as it perpetuates stereotypes about beatnik culture. All of the students speak in jive and several are portrayed as sex-obsessed, while Zugsmith takes great pleasure in rubbing the audiences’ face in smutty content. Please don’t take this as overly critical. High School Confidential is a riot from start to finish, partly as it can’t help being a little fond of the subculture it is ‘warning’ against.

Ellroy was quite taken by the attractive actress Phillipa Fallon, whose reading of the beat poem ‘High School Drag’ is the highlight of the film. Do you see elements of Ellroy’s bookstore performances in this jive kats?

Vampira and The Beat Generation

Zugsmith followed High School Confidential with The Beat Generation. Once again, it’s a crime film drowning in beatnik satire. The basic premise is chilling. Ray Danton plays Stan Hess, aka ‘The Aspirin Kid’. Hess is a rapist who worms his way into women’s homes while their husbands are away. Charming and handsome, Hess knocks at the door claiming that he owes the woman’s husband money. Once inside, he feigns a headache and pulls out a tin of aspirin. While the woman is distracted getting a glass of water for him, Hess sneaks up from behind, assaults and rapes the woman.

Although he doesn’t murder his victims, Hess could be modelled on the serial killer Harvey Glatman. Known as the ‘Glamour Girls Slayer’, Glatman selected his victims by contacting aspiring models with offers of work. While in prison, Glatman was interviewed by detectives in connection with Jean Ellroy’s murder. As if the film couldn’t get more Ellrovian, Dick Contino performs a song at the climactic ‘Beat Hootenanny’, wherein Hess and Detective Culloran (Steve Cochran) fight it out amid a group of enraptured beatniks, who happily sing and dance and are completely oblivious to the duel unfolding before their eyes.

The Beat Generation features an actress who is referenced in Ellroy’s White Jazz. Maila Nurmi was a Finnish-American actress better known as Vampira, a character she created as the host of The Vampira Show. Part Two of White Jazz is titled ‘Vampira’, although reference to the character is quite brief. Dave Klein spots the portrait of ‘a ghoul woman’ on the shelf of Glenda Bledsoe, an actress he is keeping under surveillance for Howard Hughes. Glenda says of Vampira:

She’s the hostess of an awful horror TV show. I used to carhop her, and she gave me some pointers on how to act in your own movie when you’re in someone else’s movie.

The mention of Vampira must be something of a turn-on, as Klein struggles to hide his attraction for Glenda when she is describing the horror host: ‘Shaky hands – I wanted to touch her.’ Billed as Vampira, the alluring Maila Nurmi appears in The Beat Generation as ‘The Poetess’. She recites a beat poem, not dissimilar to ‘High School Drag’, with a cigarette in her hand and a white rodent on her shoulder. Although the poem is typically hilarious, the scene is quite chilling. Detective Culloran is watching The Poetess, and her recitation is interspersed with clips of Hess who is at that moment using his usual routine to enter Culloran’s house:

Love Me Fierce in Danger: The Life of James Ellroy is available for pre-order from Bloomsbury.