Once a World by Craig McDonald – Review

Once a World is the latest novel by Craig McDonald in the Hector Lassiter series. Lassiter is a writer and a warrior. He’s not a soldier of fortune, but he does find himself drawn to bloody conflict and violent intrigue partly as a means to inspire his writing. He was born on January 1, 1900, and his eventful life takes the reader through the twentieth century – one hundred years which certainly had enough brutal episodes for a budding adventurer and scribe to document or turn into fiction. Novels in the series so far, which has never been chronological in design, have put Lassiter in the Spanish Civil War (Toros & Torsos) and at the Liberation of Paris (Roll the Credits). For a comprehensive overview of the Hector Lassiter character, series and its inspirations check out my interview with Craig on this site.

Once a World is the latest novel by Craig McDonald in the Hector Lassiter series. Lassiter is a writer and a warrior. He’s not a soldier of fortune, but he does find himself drawn to bloody conflict and violent intrigue partly as a means to inspire his writing. He was born on January 1, 1900, and his eventful life takes the reader through the twentieth century – one hundred years which certainly had enough brutal episodes for a budding adventurer and scribe to document or turn into fiction. Novels in the series so far, which has never been chronological in design, have put Lassiter in the Spanish Civil War (Toros & Torsos) and at the Liberation of Paris (Roll the Credits). For a comprehensive overview of the Hector Lassiter character, series and its inspirations check out my interview with Craig on this site.

Three Chords & The Truth (2016) brought the series to a nominal end, but now Lassiter is back again in Once a World, a thrilling portrayal of his early life which reveals how by the age of eighteen Lassiter was already a battle-scarred veteran of the Punitive Expedition and the First World War, events alluded to in the previous novels.

We are first introduced to Lassiter as a boy growing up in Galveston. A horrific event leaves him an orphan and he is raised by his wily conman grandfather Beau. While Beau is giving him an education in various complicated swindles, Hector’s first love, the beautiful older woman Hudson Bay Leroux, makes a man of him in the bedroom. However, it is not long before Lassiter feels the need to prove himself on the battlefield as well as in the boudoir. Some military experience, he feels, would help him find his voice as a writer. Lassiter is in Columbus, New Mexico on the night that Pancho Villa launches his foolhardy raid on the border town. Despite being underage, Hector signs up for the Punitive Expedition to capture Villa. At the age of sixteen, Lassiter finds himself travelling through the treacherous Mexican desert with the US Army. Faced with inhospitable conditions and vengeful natives who regard them as invaders, Hector and his comrades soon discover the reality of war, which is a far cry from how it appears to adolescent boys searching for glory. Lassiter wants out, but there is a problem. Due to events loosely connected to the Expedition, America is about to get embroiled into a far deadlier conflict in Europe, and Lassiter has made an enemy of a certain Captain George S Patton Jr. who is determined to put the young soldier in as much danger as possible. There’s a great gag about how Patton has to be restrained from striking Lassiter in a military hospital.

In addition to Patton, Lassiter also encounters such seminal figures as Ambrose Bierce, John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos and one other important historical figure whom I shall return to in a moment. With so many characters present from the literary world, it is not surprising that Once a World is one of the best novels you could read if you want to learn about the process of writing. Lassiter writes in hotel rooms and hospital beds, on scraps of paper on lonely desert nights, and huddled down in mud-filled trenches by fading light. Observations and thoughts evolve into booze-fuelled anecdotes and then into the written word, and the reader begins to see how Lassiter will become a successful writer, as episodes of his life are part of a larger ongoing narrative he can only faintly conceive as a young soldier. McDonald beautifully captures the ironies of an author’s life: what a writer conceives in anxiety is often read and interpreted years later as hard-bitten wisdom. And there’s plenty of wisdom and other delights in Once a World. It is a brilliant evocation of a brief but bloody chapter in American history, and it can easily stand alongside the best of Gore Vidal’s Narratives of Empire series in its portrayal of a lost, and too often forgotten, world.

Postscript: I said I’d come back to one historical figure who appears in this novel. Armand Ellroy makes a cameo as one of the soldiers on the Punitive Expedition. Armand was the father of James Ellroy. As his son would attest to, Armand was known for telling whopping lies, such as his claim that he was Babe Ruth’s manager. Armand owned a chestful of medals that even his family didn’t believe he had entirely earned on the battlefield. It is doubtful that Armand was ever part of the expeditionary force that tried to capture Pancho Villa, but he did serve in the military during the First World War. One of my favourite quotes from the many interviews James Ellroy has given is when he says of his father:

I saw a picture of him with his World War I outfit and, you know, there he is. I mean, that was him. It was taken on Armistice Day, so he was over there on Armistice Day. And there he is. That’s him. You can tell.

PJ Tracy is the pseudonym of the mother-daughter writing team of Patricia ‘PJ’ and Traci Lambrecht. Their debut novel, Monkeewrench (2003), was hugely successful and launched their popular series of novels featuring Detectives Gino and Magozzi who investigate complex and grisly crimes in modern day Minnesota. Sadly, PJ Lambrecht died in 2016. Traci Lambrecht has continued writing the Monkeewrench series since her mother’s passing, still using the PJ Tracy pseudonym. Ice Cold Heart is the tenth and latest novel in the series. It is a gripping thriller, full of twists and turns, which offers a vivid insight of modern day dangers the police grapple with in our technologically advanced society.

I was delighted that PJ Tracy agreed to an interview with me. The following exchange took place by email:

Interviewer: Tell us a little about the creation of the Monkeewrench series and Detectives Gino and Magozzi. Where did these ideas and characters come from?

PJ Tracy: PJ and I have always loved a good mystery and solving puzzles, so crime thrillers were a natural for us. In 2002, when Want to Play? was written, the digital age was in its nascence and PJ and I saw endless potential for a group of eccentric computer geniuses. My father was an original computer geek, working in the field since the early 1970’s, so we had many acquaintances that provided excellent source material, both in regard to characterization and plot possibilities. The Monkeewrench gang is part amalgamation of people we knew, and part creation of people we would love to meet at a party. PJ worked with attorneys and law enforcement for several years, so the detectives were crafted in a similar way. And of course, we imbued a healthy dose of imagination and they all took on lives of their own. I half-expect to receive Christmas cards from them all!

Interviewer: A lot of novelists would balk at the idea of a co-writer, but you have always spoken very warmly of working with your mother PJ Lambrecht. What was it like writing the novels with her and how did you resolve any disagreements about the narrative?

PJ Tracy: Writing with her was an honour and an absolute delight. For two women who wrote about some pretty heavy subject matter, we were laughing constantly. The back and forth, the flow of creativity during our writing sessions, was magical. From the time I was a very little girl, we were always creating characters and writing stories together, and that was the genesis of our future working relationship. She always joked that we shared a brain, but in truth, we melded them and created a voice that was neither hers nor mine, but a unique, collaborative one. As close as we were, it was a seamless process. We rarely had disagreements, but on the rare occasions we had divergent visions, we would talk through them like adults and decide which direction would best serve the book.

Interviewer: Now that you are writing the novels on your own, how would you describe the direction of the series?

PJ Tracy: After ten novels, it’s a very natural progression, I don’t even think about it. It’s terribly hackneyed to say this, but it’s true that the characters do all the heavy lifting and they always surprise me. I’m just along for the ride.

Interviewer: How do you see Gino, Magozzi and the other regular characters as changing over the course of the series? Are they very different people from when the readers first met them?

PJ Tracy: All the characters, particularly Magozzi and Grace MacBride, have experienced tremendous arcs throughout the series. Even the secondary characters have evolved in substantive ways, and are in very different personal places than they were at the beginning. I’m also a different person than I was sixteen years ago at the series’ inception, so I’m certain I transposed some of my own development and journey onto the characters.

Interviewer: Ice Cold Heart deals with some dark themes, including everything from BDSM to War Crimes. How do you approach handling these disturbing and sensitive themes as a crime writer?

PJ Tracy: That’s a perennial challenge, finding the proper balance between dark and light, both in fiction and in real life. For me, the key is focusing not so much on the horror of a particular crime, but on the humanity of the characters as they are impacted by tragedy. Homicide precludes a happy ending for the victims and their families, so the service of justice is paramount and allays some of the inherent darkness.

ZaSu Pitts and Jean Ellroy: Kindred Spirits?

In his memoir My Dark Places, James Ellroy writes that his mother Jean Ellroy ‘had a full-time gig at St John’s Hospital and wet-nursed a dipsomaniacal actress named ZaSu Pitts on the side.’

ZaSu Pitts was an actress and comedienne who enjoyed a career of remarkable longevity by Hollywood standards. She made her film debut in 1917, and her final role was a cameo in the all-star comic extravaganza It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World in 1963. She loved mystery fiction, and found herself embroiled, quite by chance, in some of the strangest mysteries in Hollywood history. However, real-life mysteries that take place outside of the confines of paperback novels have tragic repercussions, and Pitts was deeply affected by the premature deaths and suffering endured by some of her closest friends. As her health began to decline in the 1950s, Pitts underwent a series of operations and hired a private nurse named Jean Ellroy (whose son later became one of the most acclaimed crime writers of his generation). In this article, I am going to investigate ZaSu Pitts’ professional and personal relationship with Jean Ellroy.

Pitts’ biographer Gayle Haffner gives a detailed account of the health problems Pitts endured that led her to meeting Jean Ellroy. In 1952, while on tour of New England, Pitts discovered a lump in her breast. A biopsy confirmed it was a tumour and Pitts underwent a lumpectomy. The surgery was successful, but ‘it was difficult for ZaSu to move her arm and perform certain body movements without feeling a pinching or jabbing of pain’. In 1954, Pitts noticed the lump had returned and this time she underwent a full mastectomy. She was convalescing at St John’s Hospital for a week after the operation. She was discharged only to be readmitted two days later in intense pain. She was advised that a private duty nurse would need to check up on her every day. According to Haffner, ‘One of the charge nurses, an R.N. named Jean Ellroy had cared for her postoperatively, and knew exactly how to manage the medications, bandages and other personal care.’

Jean took on the role, which she was grateful for as 1954 was also the year she decided to divorce her husband, Armand Ellroy, and the extra money would be useful to pay for an attorney. She also transferred her son to a private school named Children’s Paradise which ‘set my mother back 50 bucks a month’ Ellroy wrote.

Haffner describes Jean as being a great help to Pitts:

If current medications were ineffective for pain control, (Jean) Ellroy would make adjustments and discuss options regarding different drugs. When ZaSu showed some concern over the use of injectible pain killers, Ellroy confided that in the hands of a professional any such medications could be safely administered and would not necessarily lead to a drug dependency.

Haffner’s account of Jean Ellroy’s nursing of Pitts is impressively, one might say suspiciously, detailed. There are a few howlers, though, which undermine its authenticity. She refers to Jean’s son as ‘Jimmy’ and her husband as ‘James Sr.’ Ellroy’s father alternated between his first and middle names Armand and Lee. He occasionally employed the pseudonym ‘James Brady’, but this was strictly as a tax dodge for work, and he wouldn’t have used it in the family home. James Ellroy was born Lee Earle Ellroy. He didn’t take the name James until long after his parents died, and there is no reference to them ever calling him ‘Jimmy’. Also, Haffner uses Ellroy’s memoir My Dark Places as a source for her portrayal of Pitts and Jean Ellroy’s meeting, but its difficult to see how useful the book was when Ellroy only gives Pitts a passing mention. For instance, Haffner cites My Dark Places as evidence that Jean was complaining at home about Pitts neediness: ‘Years later her little son would recall his mother’s complaints about her patient, ZaSu Pitts.’ In My Dark Places, Ellroy never claims his mother complained about Pitts. In fact, in his essay ‘Where I Get My Weird Shit’, Ellroy recalls his mother describing Pitts as ‘a sweetheart and a pleasure to nurse.’ Incidentally, Pitts had a recurring role as a nurse in the Francis the Talking Mule film franchise. The first film, in this hugely successful series, had been due to be produced by Armand Ellroy’s close buddies Mickey Rooney and Sam Stiefel. But Rooney and Stiefel passed on the project as they never saw the appeal of the character, and missed out on a small fortune as a result.

Haffner has written an entertaining and readable biography of Pitts, and its clear from the acknowledgements that she interviewed hundreds of people as research. But perhaps Haffner approached the Pitts-Jean relationship as a historical novelist would. She knew Jean Ellroy had treated Pitts, and she decided to creatively expand on the details of their meeting. But perhaps James Ellroy also erred in his depiction of Pitts. Ellroy wrote that his mother did wet-nurse work for Pitts as she was a ‘dipsomaniac’. Neither of Pitts’ biographers (Haffner and Charles K Stumpf) refer to the actress having a drinking problem. This contradiction between Ellroy and Haffner’s accounts is intriguing. Today, Hollywood stars can get the best treatment for addiction that money can buy, but in the 1950s alcoholism was taboo, and it’s easy to imagine that if Pitts needed to detox it could be handled discreetly, at home, with Jean Ellroy’s assistance. It’s also possible Ellroy was simply mistaken about his mother’s role in caring for Pitts alleged dipsomania.

If Jean did treat Pitts for alcoholism, she must have drawn on her own experiences and struggles with the bottle. As Ellroy details in My Dark Places, Jean had first encountered both the allure and dangers of alcohol from an early age, growing up in Tomah, Wisconsin. Her father, Earle Hilliker, was an alcoholic. He was fired from his position as a forest ranger after being found drunk on the job by the State Conservation Boss. It also cost him his marriage. He was transferred to Bowler Ranger Station, over one hundred miles north-east of Tomah. His wife Jessie refused to go with him, preferring to raise Jean and her sister Leoda in Tomah. Jean moved to West Suburban College (now Resurrection University) in Chicago in the early 1930s. With this new-found freedom she developed a fondness for alcohol. She and her dorm-mate Mary Evans became experts at breaking curfew and sneaking back unnoticed after a night on the town. After one boozy evening, Jean lit a cigarette while she sat on the toilet. She carelessly dropped the match in the toilet bowl where it set the toilet paper on fire and singed her bottom. ‘Jean laughed and laughed’ about the incident Ellroy wrote.

In a one-off job, Jean was paid to drive an elderly married couple from Chicago to New York. The couple were planning one last trip together, an Atlantic voyage to Europe, as the wife was dying of cancer. They were both alcoholics and Jean was told to keep them sober: ‘The drunks wandered off at rest stops. Jean found bottles in their luggage and emptied them. The drunks scrounged up more liquor.’ Eventually Jean encouraged them to drink so they could ‘pass out and let her drive in peace.’ Jean had learned something about the mindset of alcoholics, but once the job was over she went on a bender to unwind. The couple let Jean use a hotel suite booked in their name. Jean had her friends from Chicago visit and ‘they partied for four or five days.’ Ellroy is candid in writing about his mother’s fondness for alcohol and partying, but he is careful to state that it did not affect her schooling or career ‘Jean knew how to balance things […] She could stay out late and perform the next day. Jean was competent and capable and deliberate’. Indeed, Jean’s academic achievement and prodigious work ethic, especially in comparison to the ironically teetotal Armand Ellroy, attests to the fact that she could largely control her drinking.

Jean Ellroy was murdered in El Monte on June 22, 1958. Haffner writes of Pitts learning the news of Jean’s murder in the LA press:

June of 1958 was already hot and sweltering. Hoping to relax for the evening, the Woodalls (ZaSu and her second husband Eddie Woodall) opened up the Los Angeles evening newspaper to find full of coverage on a grisly murder which had taken place just Saturday night.

We can only speculate, as Haffner does, about Pitts and Jean’s time together. Did Jean confide to Pitts about her failing marriage? Pitts knew a thing or two about bad marriages, so it’s certainly possible. Her first marriage, to Tom Gallery, had ended in divorce after a long separation. Gallery’s faltering acting career appears to have been one of the reasons the marriage failed. His nadir as an actor came when he was bitten by Rin Tin Tin and nearly burned alive in a stunt gone awry. Gallery quit Hollywood to become a successful sports promoter.

As for Pitts second marriage to Eddie Woodall, part of the reason she needed Jean Ellroy was that ‘waiting on her or being of any consolation was beyond Eddie’s character. He was a rogue and she knew it.’ Haffner draws a parallel between Pitts adoption of her friend Barbara LaMarr’s son Marvin (subsequently renamed Don Gallery) after LaMarr’s premature death, and James Ellroy’s upbringing with his father after the murder of Jean Ellroy. Pitts was able to give Don Gallery a loving home and all of the benefits a privileged Hollywood upbringing has to offer. Armand Ellroy truly loved his son, but he had neither the money nor the inclination to successfully raise a child alone.

Pitts’ cancer recurred and she died on June 7, 1963, almost five years to the day that Jean was murdered. ZaSu Pitts was one of only hundreds, probably thousands, of patients Jean would have nursed during her medical career. We might never know if, in addition to post-operative care, she was helping Pitts deal with a drinking problem. But we can say with a degree of certainty that she showed kindness towards ZaSu Pitts, a kindness that both women had found lacking in their husbands.

The two women had more in common than they may have realised.

Mr Campion’s Visit – Review

It’s 1970 and an aging Albert Campion is appointed Visitor to the newly constructed University of Suffolk Coastal. Campion finds the role of Visitor as baffling as the murky world of academe itself. It’s not clear what his employers expect him to do, except give the occasional speech to oversexed undergraduates. The campus has been built on the site of Black Dudley, the stately home which, forty years earlier, was the setting of the very first Campion novel. It’s tempting to say Campion hasn’t changed much over the intervening forty years even if the architecture has. Medieval cloisters have been swept away in favour of modernity and the Brutalist architecture which was popular in 1960s and 70s Britain. Campion himself is still urbane, flirtatious and masking a sharp mind behind his other-worldly manner. That said, the excellent Mr Campion’s War revealed the murky acts of espionage Campion committed for Blighty during the war have hardened his soul, and the rapid changes happening in post-war Britain have given him reasons to become more cynical with age. Despite this, he still lights up at the thought of a good lunch and a mystery to be solved.

It’s not long before a death on campus gets Campion back to his more natural role as a sleuth. Professor Pascal Perez-Catalan is a geochemist whose brilliant career is cut short when he is found with a knife in the back. The Latino Don was noted for his fiery left-wing views (he supports Salvador Allende in his native Chile), and his unparalleled skills of seduction. So was his murderer a right-wing fanatic, a rival colleague, spurned lover or a jealous husband? Campion must get to the bottom of it all. On his way, he stumbles across the mysterious ‘Phantom Trumpeter’, who plays the Last Post every midnight without fail, and wrestles (almost literally) with giant outdoor chess pieces. Budding chess players on campus can play a game against one of those newfangled computers, an invention which Campion’s loyal manservant Magersfontein Lugg confidently predicts will never catch on.

Mr Campion’s Visit is another triumphant addition to the Campion series by Mike Ripley. It’s both engrossing as a mystery and frequently very funny in its depiction of academe. This reviewer has visited the campus on which the University of Suffolk Coastal is based –trust me, Ripley nails it! In fact, one might say that Mr Campion’s Visit has all of the elusive qualities of an ideal academic– it’s eccentric, effortlessly witty, detached (in the best possible way) from the real world and fizzing with great ideas.

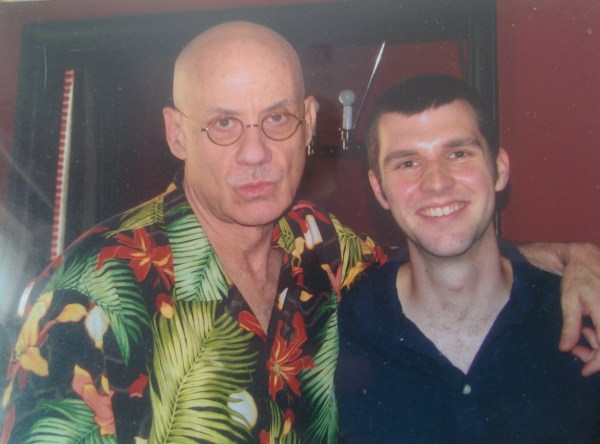

Ten Years of the Venetian Vase

Ten years ago this week Chris Routledge and I began the Venetian Vase blog. At the time we were working together on the book 100 American Crime Writers, and Chris thought we should set up a website to either directly promote the book or one that would look at crime fiction more broadly. I favoured the latter option as I thought it would give the site more longevity. Chris has since moved on to his own projects, but I remain eternally grateful to him for helping me set up this blog and, as a Raymond Chandler fanatic, coming up with the name.

It took some time, and a lot of hard work, but I think the Venetian Vase found its voice as a blog which publishes in-depth research on genre fiction. Oh, and if you enjoy the work of James Ellroy then this is the blog for you.

I owe a big debt of gratitude to everyone who has contributed to this blog – Diana Powell, David Hering, Chris Pak, Steve Hodel, Craig McDonald and, most recently, esteemed Ellrovian Jason Carter.

Thank you to all past, present and future readers, and a big thank you to the Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction.

Here’s to the next ten years.

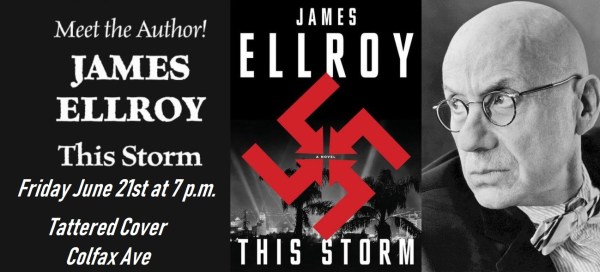

When I interviewed Ellroy at his home in LA in 2009, the year I started the blog

Meeting Ellroy ten years later in Manchester 2019, while he was on tour promoting THIS STORM

THIS STORM: Ellroy comes home

For the following post we welcome back to the blog James Ellroy aficionado and all-round good guy Jason Carter.

It’s the summer solstice, and it’s shitting rain.

Normally I hate storm clouds and rain during summertime, but today it’s rather appropriate.

Under a water-logged and overcast sky on Earth’s longest day, I entered the Tattered Cover, an iconic Denver literary institution. Nearly a decade ago, (October 22, 2009) I met James Ellroy for the first time at this boss bookstore on Denver’s Colfax Avenue, often regarded as the longest street in the U.S., and the annual locale for a badass Denver marathon. It seems appropriate then, that the Dog would return to this same location in his now hometown to introduce his new literary symphony, the ravishingly raucous and rain-reamed This Storm.

I’ve heard Ellroy’s “Peepers, prowlers, panty-sniffers” schtick plenty of times (it never gets old) but it’s always enjoyable to watch the shocked and astonished responses from people whom have never experienced an Ellroy reading. Typically, these unlearned ones are quiet, conservative little old ladies, and there were quite a few in attendance.

Beyond that, the audience—pock-marked with refugees from the sunken Alamo Drafthouse—was much more diverse this time than in 2009, and I’d like to think there were plenty of new and potential Ellroy fans present. Right from the start, Ellroy told the double-digit crowd to refrain from asking him any questions pertaining to contemporary American politics and/or the current occupant of the White House. “I live history, I breath history. It’s not 2019. I pay no attention to what some people have called a tumultuous political climate.” This Storm and only This Storm was the star of the show.

“This Storm and Perfidia celebrate the hard-charging, shit-kicking World War II America,” Ellroy began, calling his new novel “an instant American bestseller published to thunderous acclaim.”

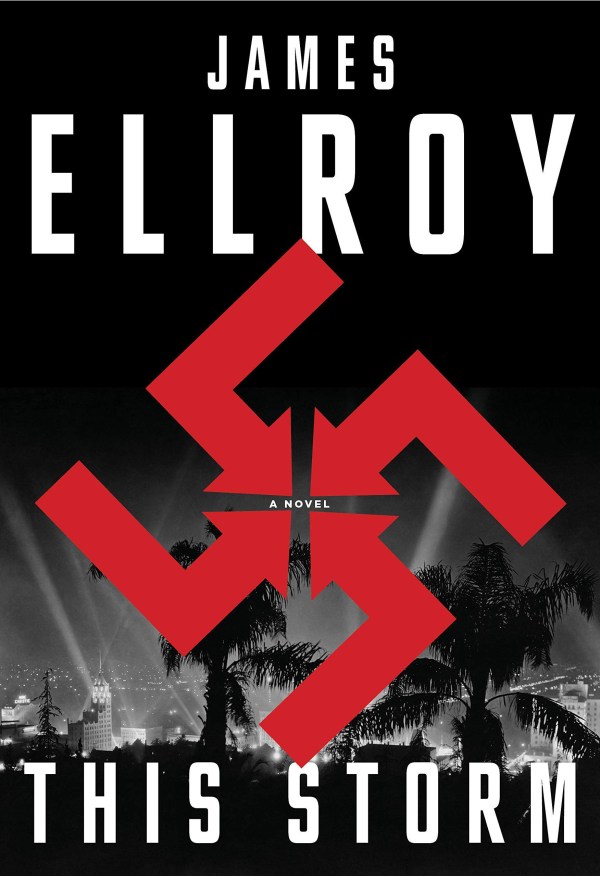

Regarding the novel’s incendiary cover art, Ellroy bludgeoned any ruffled sensitivities. “Dig it, it’s a Swastika—can ya dig it?” the Dog taunted. “Live with it, it’s ok, calm down right now.”

Ellroy’s trademark profanity was a dynamic and conspicuous no show throughout the night, and there was a respectful and dignified reason for that: Tattered Cover’s presentation dais just happens to be in the middle of the children’s and young adult literature, so in a display of his copious morality and empathy, the Demon Dog went fuck-free, and even refused to read any passages from the book in regards for the numerous young children there. It was absolutely the right call. “There’s nothing I can read in this book that doesn’t have any reference to sex or pornography or profanity, so I’m not going to,” Ellroy told us.

“I expanded the text to enhance the emotional lives of the protagonists,” Ellroy said of the book’s production, launching then into brief summaries of most of This Storm’s major characters. “I live with their eyes. I breathe with their soul… I loosened the constraints of my admittedly sometimes constricting staccato short sentence style in order to give you intimate access to my protagonists, who are the wildest bunch of mofo’s I’ve ever written in one book.”

Plenty of patrons asked Ellroy questions, though most of them weren’t about his new book. Helen Knode, the Demon Dog’s second ex-wife and current girlfriend, was seated directly behind me, and asked most of the Storm-specific questions. “Helen’s read the book,” Ellroy said, pointing at her.

I asked Ellroy whether he felt Joan Conville was the novel’s conscience, and even quoted how the red-headed army nurse admonished Whiskey Bill Parker just like a guilty conscience would. He seemed to like my idea, somewhat. “No, Kay Lake is the conscience of the novel, but yeah…”

Always a master of nuance, the Demon Dog also threw his loyal readers a bone that may just explain his endearingly contradictory ways: “I’ve got the twin influences of my life in my head at all times: One, the Lutheran church, two, Confidential magazine: the moral vision and the sin at full blast, and F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that the definition of an artist is someone who can hold concurrently two diametrically opposed points of view and retain their sanity… that’s me.”

Before closing out his speech with his standard recital of Dylan Thomas’ “In My Craft, or Sullen Art,” the Demon Dog left us in no uncertainty about his historical impact: “Who’s the greatest artist ever spawned by civilization? To me, it’s Beethoven, and if I am indeed the American Beethoven, I would call Beethoven the German Ellroy.”

It’s quite common for successful writers to be asked “what advice would you give to aspiring writers?” Most get away with “write what you know,” but Ellroy has for many years delivered a far more personal and pertinent instruction: “Write the kind of book that you like to read.” Tonight, he expanded on the genesis of that wisdom. “I was always looking for a giant book that would hold me longer than four or five days… Nobody was writing these books, and so many, many decades later—now—I don’t write what I know, as much as I write the books I wish I could’ve read as a kid that nobody else was writing.” I can relate to that. I waited years and years for a writer to directly explore Ellroy’s countless contradictions, and it never happened… until I did it myself.

Watching the Demon Dog interact with his fans afterwards gives you the sense that anyone who has ever accused Ellroy of being a pessimist and a misanthrope would stand severely corrected if they ever attended the autograph component of an Ellroy book reading (try it out sometime, Mike Davis). Ellroy was in great spirits this evening, and his enthusiastic gratitude seemed to pervade the whole room. In short, whomever said you should never meet your icons, has clearly never met James Ellroy.

When it came to my time, Dog signed both my hardcover and uncorrected proof of the book, and though we didn’t have much time or room to talk, the Reverend Ellroy endowed me with an august benediction: “Keep reading, big Jason”.

Yes sir, I certainly will.

Welcome home, Dog.

Jason Carter

THIS STORM: Patterns across history

For the following post we welcome back to the blog James Ellroy aficionado and all-round good guy Jason Carter. Here is Jason’s take on James Ellroy’s latest novel This Storm.

It’s all one story, you see.

James Ellroy has always taught us—and me in particular—to seek the design amid the dissonance.

In a 2018 piece published on the Demon Dog’s 70th birthday, I concluded by anointing Ellroy’s ever-ambitious output as an ultra-marathon with no finish line, at a time and age when many people are eyeing retirement the way L.A. Confidential’s Salvation Army Santa eyes the liquor store across the street.

Ellroy’s latest novel This Storm, the midway point in the Dog’s second L.A. Quartet, boldly confirms this, as its blistering pace and pugilistic prose (Ellroy’s sharpest narrative since The Cold Six Thousand… you’ll need stitches on your tongue after reading it aloud) depict a rain-soaked L.A. in a graffiti fever dream of paranoid chaos…

It’s the dawn of 1942. The wounds from Pearl Harbor are still open and bleeding, and the disgraceful roundup of Japanese Americans is in full swing. Boozed out army nurse Joan Conville mows down four Mexican dope peddlers while en route to her first day of duty… It’s the first wave of a monsoon-like tempest of death that awaits the City of Angels. The incessant rain sparks mudslides that unearth a charred corpse in Griffith Park, and later, two dead LAPD detectives are discovered in a downtown klubhaus frequented by gays, black jazz musicians, and fifth columnists. As any Ellroy reader knows, these disparate strands will eventually dovetail towards the end.

The two dead cops in the downtown klubhaus presents a major conflict: Should the LAPD work the case, or protect the department’s reputation? Chief Jack Horall wants the klubhaus kase krushed, ordering “a clean solve [with] dead suspects who will never enter a courtroom” while Captain William H. Parker is struggling to contain a soul-crushing truth (revealed at the end of Perfidia) that could stain the department for generations.

The redheaded Joan Conville, whom Ellroy based on his own mother, is blackmailed into the LAPD after that auto accident. Rather than a vehicular manslaughter charge, Conville accepts a job in the department’s crime lab, where her superb analytical and deductive work soon make her a valuable asset. Ms. Conville, a flawed mother figure, and at times the novel’s ostensible conscience, admonishes Parker for keeping a secret that’s eating him alive. “How can you live with what you know, and do nothing?” she asks him.

Character cameos from Ellroy’s previous two bodies of work are greatly minimized this time, but far from absent. Joan Klein, the 40-year-old Red Goddess and revolutionary mother figure in Blood’s A Rover is here as a 15-year-old revolutionary in training, mentored by the Red Queen Claire DeHaven, Ms. Conville, and even a certain army captain named Dudley Smith (although, Smith seems to distrust Young Joan from the beginning). Those of you familiar with Blood’s A Rover may need to re-read that novel’s chapter 119, which details Joan’s full backstory… I know I certainly did.

Along the way, Joan Conville romantically intertwines herself with rivals Parker and Smith. Ellroy refers to this arrangement as triangulation, and it’s something he’s used quite often before, most notably in The Black Dahlia, and L.A. Confidential.

The ensuing investigation uncovers that the two dead cops at the klubhaus had ugly pasts and a twisted familial arrangement that evokes White Jazz’s equally demented Herrick and Kafesjian families. This obvious evocation recalls something Jim Mancall mentioned in his 2014 companion to Ellroy’s work: Concerning Blood’s A Rover and its narrator Don Crutchfield, Mancall discusses how Crutch, like astute Ellroy readers, searches for clues to understand historical events. As Crutch searches, “readers link patterns across disparate contexts, searching for larger meanings.” Ellroy also seems to pay respectful homage to Ross Macdonald, one of his greatest teachers, with Conville’s subtle assurance that “It’s all one story, you see,” echoing the former Kenneth Millar’s famous adage “it’s all one case.”

It’s difficult not to think of The Big Nowhere’s Danny Upshaw when you read This Storm’s depiction of homosexual Japanese LAPD chemist Hideo Ashida, who even employs Upshaw’s Man Camera to reconstruct the klubhaus krime scene.

Army Captain Dudley Smith is a fascist fetishist here (in the words of Joan Conville), and as expected, concocts countless schemes to reap profit from war. Smith’s collision course with William Parker foreshadows the Dubliner’s White Jazz standoff against Ed Exley some 16 years later. Smith is also severely de-LADded here, so much so, that I wonder if Ellroy’s editors pressured the Dog to tone down his Irish icon’s most distinctive quirk. This is, however, the least of Mr. Smith’s problems in this novel… more on that below.

It’s great fun to see Ellroy put his palpable hatred for Orson Welles into action. I’ve known for quite some time that Ellroy thoroughly detested Welles, though I’ve tried to get the Dog to at least admire Welles as a skilled radio performer (Orson will always be The Shadow to me) and a national prankster. But, in This Storm, the Demon Dog paints the Citizen Kane wunderkid in a light similar to American Tabloid’s JFK: A loser and a buffoon behind the scenes who falls mightily short of his God-like public image. Ellroy even gives an indication towards the bloated behemoth has-been that Welles, who in the novel is muscled into becoming a police informant, would become in later decades (“he eats too much…”).

Though far faster than the plodding Perfidia, This Storm is far from a perfect storm. The Dudley Smith in The Big Nowhere through to White Jazz could kick the bloody shit out of This Storm’s Dudley, who’s a “dud” in more ways than one… It was always a hilarious blast to read Smith, with his inimitable charm melded perfectly with his systemic evil. However, in This Storm, I find it hard to relate to this opium-smoking, kimono-donning, wolf-communing Smith caricature versus the fearless Irish ass kicker in the earlier (later?) books.

At least it’s comforting to know Mr. Smith will toughen up as Ellroy’s chronological 31-year narrative unfolds. I just hope that transition begins within the framework of this new quartet. It pains me to say this, (and rather feels like I’m spitting in the face of my uncle) as I literally grew up reading about Smith, but whereas before I was laughing with Dudley, here I am most certainly laughing at him.

Like all of Ellroy’s work, This Storm’s nightmarish indelible images linger long after the last page. It’s a literary hurricane that will invade your subconscious, and force contemplation…You’ll find yourself thinking about its machinations at odd intervals and even odder hours. In spite of its problems, This Storm makes me excited for volume three.

One final note: Even before the novel existed, This Storm had a turbulent genesis with mind-blowing unintended consequences that more than lived up to its anagrammed admonishment (shit storm). I was even an unwitting catalyst for the ensuing debacle. There’s a wild and tragic tale behind it all, and I promise I’ll tell it to you someday… Off the record, on the QT, you know the rest…

Jason Carter

James Ellroy’s THIS STORM – Review

James Ellroy is a living legend among crime writers. Of the more than twenty books he has authored, I would count at least six — The Black Dahlia (1987), The Big Nowhere (1988), White Jazz (1992), American Tabloid (1995), My Dark Places (1996) and The Cold Six Thousand (2001) — as masterpieces. You may disagree with my choices, but in my view these are the most flawless works of literature that Ellroy has created. And of course there are the seminal early novels, the gripping Lloyd Hopkins trilogy, unforgettable short stories and hard-hitting articles which, taken all together, amount to an incredibly rich and powerful contribution to the crime and historical fiction genre.

So, after giving him such a glowing introduction, you may have already guessed that my assessment of Ellroy’s latest novel This Storm is that it doesn’t belong with his best work. In fact, any reader who has struggled with Ellroy’s recent output is going to find This Storm difficult. At times it is maddening. But having read the novel twice now, and been quite disappointed at first, I have come to admire its scope, ambition and narrative power more on the second reading.

This Storm begins where Perfidia left off. Isolationism has failed America just as Appeasement failed in Britain. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour means America is now at war with the Axis powers. This global conflict, just over twenty years on since the last one ended, will bring new opportunities to individuals ambitious and ruthless enough to exploit it. Dudley Smith is recovering from the wounds he received at the end of Perfidia. He suspects, wrongly, that Chinese Mafia figures were behind the attack. He hasn’t got much time to think about revenge though as the murder of two LAPD detectives at a local ‘Klubhaus’ sends him on a collision course with departmental reformer William H Parker. Parker has his own demons too, namely women, whiskey and a big dose of Catholic guilt. Heavy storms bear down on LA and, seemingly in an act of God, mudslides expose a charred corpse linked to the Griffith Park Fire of 1933 and, possibly, a gold bullion heist.

As a crime narrative Ellroy is on familiar ground with This Storm. But with its wartime setting, the novel reads as revisionist historical fiction concocted in a surreal pulp fever dream which feels very original. In Ellroy’s version of the war, we don’t get to see the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, but we are given tantalising glimpses of a meeting between Nazi and Soviet high-brass in Mexico. Ellroy doesn’t portray the Night of the Long Knives, but he does have a bizarre sex party reenacting the massacre in a plush Brentwood mansion. Ellroy is in different territory than many more conventional depictions of World War Two. War may be horrific, but for many in LA, it was a chance to live fast and get rich.

There is a thread of humanity that runs through this tale of deceit and avarice. It sometimes reads like Ellroy is concocting a fantasy version of his parents’ lives before he was born. Much of the action alternates between three settings: LA, Tijuana and Ensenada. LA is where Lee Earle Ellroy grew up. His mother took him on a childhood roadtrip to Ensenada and Tijuana. Armand Ellroy had his fateful meeting with Margarita Cansino at the Agua Caliente hotel in TJ. Ellroy makes these settings come alive in the novel as they are tied to his family history.

In the character of Joan Conville, Ellroy has written his mother into the LA Quartet and she is a lot more vibrant than some of the more familiar characters. Conville is a navy nurse from the mid-west who falls under the wing of Chief Parker to avoid a vehicular manslaughter rap. She has her own agenda, to avenge the death of her father ‘Big Earle’ Conville who died in a forest fire in Wisconsin which she suspects was set deliberately.

Of the famous real-life characters, Ellroy’s visceral hatred for Orson Welles is striking and, surprisingly, this makes him the most interesting of the Hollywood set. The constant tawdry tales of Hollyweird debauchery and Nazi fetishism get wearisome after a while, but the depiction of Welles being coerced by Dudley Smith into snitching on his leftist entourage does seem plausible and pushes the narrative forward.

However, for everything that I liked about This Storm, there was something else that grated. In a narrative spanning over five hundred pages the problems are manifold. Dudley Smith comes across as a parody the more central he is to events. He seems to think he won the Irish War of Independence single-handedly. He talks like he is directing US policy in Mexico. Although readers will be relieved to hear that Dud’s ‘daughter’ Elizabeth Short only appears briefly, and it is not too distracting. Dudley does get some comeuppance for his pomposity, but this has the potential to upset readers who thought they knew him. For instance, Dudley seems to have an incredible sexual charisma around women one moment, and then he is sexually humiliated the next. All of Dudley’s dialogue is in a conspiratorial tone. When the conspiracies unravel, he is left feeling naked and ridiculous.

Of all the characters in This Storm, the stronger ones are definitely the newer ones – Joan, Elmer Jackson and Hideo Ashida. Kay Lake is quite engaging, and I enjoyed her diary entries, partly as they are more accessible and readable than the main text. Ellroy’s prose here is the most uncompromising it has been since The Cold Six Thousand. However, no matter how much Ellroy claims this Quartet is compatible with the first Quartet, I can’t help feeling that the cerebral, classical- music loving Kay Lake of This Storm is very different to the streetwise, brassy gal in The Black Dahlia.

I’m delighted that This Storm is getting such strong reviews, and likely winning Ellroy new readers. But I felt its greatest strengths lay in a different, shorter novel. This Storm isn’t as compelling as Ellroy’s best novels but, true to form, it’s as stubbornly radical as all of the Demon Dog’s recent works.

When Joseph Knox introduced James Ellroy at Waterstones in Manchester last night, it was hard for him to contain his excitement and, as an audience member, I can vouch for the palpable sense of anticipation in the room. Knox is a young local crime writer, a former employee of Waterstones, who has authored several crime novels and whose writing, he freely admitted, owed a huge debt to Ellroy.

Ellroy walked on the stage to enthusiastic applause and read from the opening pages of his latest novel This Storm. The scene is of a bootleg radio broadcast by the ultra right-wing Father Charles Coughlin, lamenting America’s entry into World War Two:

Good evening bienvenidos, a belated Feliz Navidad, and let’s not forget prospero ano y felicidad – which means “Happy New Year” in English and serves to introduce the Mexico-at-war theme of tonight’s broadcast. And at war we are, my fellow American listeners – even though we sure as shooting didn’t want to be in the first place.

Let’s talk turkey here. Es la verdad, as our Mex cousins say. We’ve been in this Jew-inspired boondoggle a mere twenty-three days, and we’ve been forced to stand with the rape-happy Russian Reds against the more sincerely simpatico Nazis. That’s a shattering shame, but our Jew-pawn president, Franklin “Double-Cross” Rosenfeld, has deliriously decreed that we must fight der Fuhrer, so fight that heroic Jefe we regretfully must. It’s a ways off, though – because we’ve got our hands full with the Japs right now.

So let’s meander down Mexico way – where the senoritas sizzle and more HELL-bent jefes hold sway.

This served as a perfect introduction to the themes of paranoia, profiteering and extreme ideology of This Storm. As Ellroy expounded upon in the questions with Knox and the audience later, this is a novel about Los Angeles’s war, the war he imagined as a child, the war of the Quartet characters. It was a time, Ellroy explained, when people gravitated towards the most fanatical ideologies ever devised by man. And yet, his research of LA newspapers showed that there was non-stop parties going on in Brentwood, Beverly Hills and Hollywood throughout the war. Policemen, politicians, gangsters and movie stars mingled at shindigs which violated blackout drills. The birth-rate went through the roof as an impending sense of death and destruction brought on by the world’s deadliest conflict gave people a voracious appetite for sex and loot. It’s a dream setting for a historical novelist.

There were a few other tidbits that tantalised Ellrovians in the audience. Ellroy insisted this Quartet would end on VJ Day, 1945, so I guess that means Dudley Smith’s involvement in the police investigation of the murder of his illegitimate daughter Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia, will never be revealed. My instinct tells me Ellroy will do some sort of extended epilogue. It’s too big a question to leave completely unanswered.

Ellroy discussed how the character of Joan Conville was based on his mother Jean Ellroy. He gave the names of two actresses who he had grown up watching on TV and film – Shirley Knight and Lois Nettleton. Knight and Nettleton’s classic beauty, natural intelligence and superb acting skills had reminded him of his mother, and he said watching them onscreen had allowed him to vicariously live or extend his mother’s life after her unsolved murder. This was a surprising and delightful revelation. I thought I knew all of Ellroy’s artistic and emotional influences, and then occasionally he comes out with new ones.

After the Q and A was over, there was a long queue of fans waiting for Ellroy to sign their copy of This Storm. Ellroy was generous and enthusiastic, chatting and posing for photos with each person. When it came to my turn we reminisced about the interviews we did, published in Conversations with James Ellroy. I mentioned my favourite interview, conducted in his then home at The Ravenswood in Los Angeles 2009. He sighed, describing that time of his life as his nadir, and then a second or two later his beaming smile came back, and we chatted about the book and then it was the next person’s turn to meet him.

On the train back to Liverpool that night, I pondered what Ellroy had said. I knew he had been dealing with some issues in 2009, which he candidly explored in his memoir The Hilliker Curse and the novel Blood’s a Rover, but he had been so kind and encouraging to me as a young researcher that they were never apparent in our interactions. I guess it makes me doubly grateful that James Ellroy is both the writer and person he is.

Viva Ellroy!

You can find full details on Ellroy’s UK and US tour for This Storm here.

James Ellroy at Waterstones in Manchester