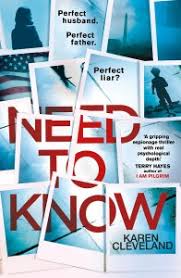

Need to Know by Karen Cleveland – Review

Need to Know is one of the most anticipated thrillers I’ve come across in years. Almost a year before publication date, it was reported that the movie rights had been sold and Charlize Theron will produce and star in the film adaptation. With such hype you might think any reading of the novel is bound to be a disappointment, but my initial reaction was one of surprise. Surprise that such a slow-burning intelligent spy novel could still be such a massive hit in an age of repetitive and action-driven vacuous franchises.

Need to Know is one of the most anticipated thrillers I’ve come across in years. Almost a year before publication date, it was reported that the movie rights had been sold and Charlize Theron will produce and star in the film adaptation. With such hype you might think any reading of the novel is bound to be a disappointment, but my initial reaction was one of surprise. Surprise that such a slow-burning intelligent spy novel could still be such a massive hit in an age of repetitive and action-driven vacuous franchises.

In Need to Know, Vivian Miller is a CIA counter-Intelligence analyst who seems like she has it all: a high-powered career tracking Russian sleeper cells in the US and a nice house perfect for raising her four kids with her loving, handsome husband Matt. But it’s not long before things start to unravel. A secret dossier at work reveals her husband is a Russian spy. She buries the evidence while she decides what to do. Cleveland gives us flashbacks to Vivian’s early relationship with Matt and how it developed. Suddenly, the mysteries of his character are beginning to make sense. Why did he always cancel planned visits for them to meet his parents at the last minute? Where did all of his money come from? The idea that you can never really know your partner is hardly new to the genre, and just when I thought this was going to be Gone Girl at Langley the story takes another turn. Vivian’s efforts to conceal her husband Matt’s true identity from her employers get increasingly dangerous, and the reader is left wondering if she choose between loyalty to her country or her love for her husband.

Cleveland spent eight years working as a CIA analyst, and she joins the growing ranks of retired spooks writing spy novels. Thankfully, she brings her knowledge of real-life espionage to add realism to this tale. This is a world wherein spies sit in front of computers and pore over financial statements and social media messages looking for threats to national security. And yet, even if the spy trade isn’t glamorous, Cleveland makes sure its never dull. Need to Know kept me guessing right to the end as the characters are involving and sympathetic. Vivian and Matt are not lazy caricatures of spies, they have the same problems as other couples, and the reader identifies with them as a consequence.

Just before Christmas, publishers traditionally rush out ghost-written, shallow memoirs by celebrities you’ve never heard of. So, this January, I needed to know that well-written and engaging novels are still hugely popular. Karen Cleveland did that for me.

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed by Mike Ripley

Do you remember whiling away a train journey or a long winter evening with a paperback World War II yarn by Alistair Maclean? Or a well-paced thriller by Desmond Bagley? Or an expertly detailed sea adventure by Hammond Innes? If so, have you ever wondered why you don’t see novels like this anymore? Then Mike Ripley’s Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed is the book for you. Although genres such as crime fiction and sci-fi have remained immensely popular and garnered increasing critical acclaim, the old fashioned thriller, as pioneered by the aforementioned writers as well as by luminaries such as Wilbur Smith, and in the US Robert Ludlum, have slowly started disappearing from our shelves.

Do you remember whiling away a train journey or a long winter evening with a paperback World War II yarn by Alistair Maclean? Or a well-paced thriller by Desmond Bagley? Or an expertly detailed sea adventure by Hammond Innes? If so, have you ever wondered why you don’t see novels like this anymore? Then Mike Ripley’s Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed is the book for you. Although genres such as crime fiction and sci-fi have remained immensely popular and garnered increasing critical acclaim, the old fashioned thriller, as pioneered by the aforementioned writers as well as by luminaries such as Wilbur Smith, and in the US Robert Ludlum, have slowly started disappearing from our shelves.

In the end I couldn’t bear another airport lounge or AK-47 and I gave up. It was, it seemed to me, a sub-genre that had had its day. The thriller wasn’t thrilling any more

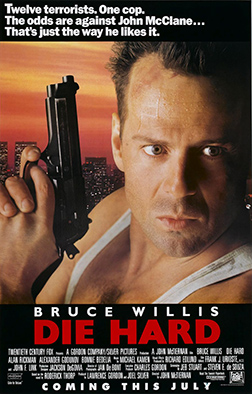

Die Hard on the Big Screen

Over Christmas I watched the original Die Hard at FACT cinema Liverpool. The screening was arranged by my good friend Dan Slattery via Ourscreen, who had helped me arrange a screening of William Friedkin’s Sorcerer at FACT at the beginning of December. Needless to say, it was wonderful seeing the film in the cinema almost thirty years after it was originally released… and even better to see it over Christmas. Yes, I’m definitely in the Die Hard is a Christmas movie camp.

Over Christmas I watched the original Die Hard at FACT cinema Liverpool. The screening was arranged by my good friend Dan Slattery via Ourscreen, who had helped me arrange a screening of William Friedkin’s Sorcerer at FACT at the beginning of December. Needless to say, it was wonderful seeing the film in the cinema almost thirty years after it was originally released… and even better to see it over Christmas. Yes, I’m definitely in the Die Hard is a Christmas movie camp.

If you read this blog, I suspect you’ve seen Die Hard as many times as I have, so, instead of doing a traditional review, I thought I’d share some of the observations of the group I went to see it with, and my own musings, as we discussed the film in the bar afterwards.

Die Hard‘s screenplay has extremely tight writing: every plot point connects. Screenwriters Jeb Stuart and Steven E. deSouza clearly believed in the Chekhov’s Gun principle in narrative, and lots of little details that occur early in the film pay off beautifully as the story moves on, such as Holly Gennaro/McClane slamming down the framed family photo in her office.

Die Hard is considered a perfect example of a Three-Act structure: set-up, confrontation and resolution (thanks to Dan for pointing this out). It becomes increasingly clear during the second act that the terrorist plot will not succeed, but at the same time, the odds are never in favour of our hero John McClane surviving. Bruce Willis deserves great credit here – he created a hero that bleeds and the audience can almost feel every punch, kick, bullet and explosion he endures along the way.

As villains go, Alan Rickman balances malevolence with comedy perfectly and his performance started the trend of British theatrical actors playing villains in Hollywood films (and could have typecast Rickman). To my knowledge he only played one more major bad guy, a very over the top Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. But, in Die Hard he gets the tone just right, relishing his evil lines and comic asides ‘Mr Takagi won’t be joining us for the rest of his life’, and never letting the all round excess of the story overwhelm his quiet menace.

The one scene I really don’t like is Sergeant Al Powell’s shooting of the terrorist Karl at the coda. It seems a triumphalist, utterly tone-deaf, way for him to overcome his accidental killing of a child years earlier which he confesses to McClane in one of the most touching scenes in the film. If it was being re-shot today, I doubt that scene would make it to the final cut. But in a way Die Hard never really ends. It was the beginning of a franchise that is still going strong today (let’s just forget about A Good Day to Die Hard), and spawned numerous imitators: Cliffhanger (Die Hard on a Mountain), Under Siege (Die Hard on a Battleship), and probably influenced the style of the later Bond films as well. Not bad for a Christmas movie.

L.A. Confidential the movie—20 years later

For our last post of 2017 we welcome back to the blog James Ellroy aficionado and all-round good guy Jason Carter. Here’s Jason’s bio:

Jason Carter is an unofficial Ellroy scholar with 20-years of Ellrovian tutelage under his belt. A devoted follower of Ellroy since the age of 14, Jason now has the enviable honor of calling Mr. Ellroy his friend. Although, don’t think of asking Jason for any personal details about Ellroy, as Jason is ferociously protective of Mr. Ellroy’s privacy. Jason, like Ellroy, lives in Denver, Colorado.

“My book, your movie…” This is James Ellroy’s expeditious way of distinguishing himself and his work from the output of Hollywood…it’s common knowledge to anyone who’s followed the Demon Dog’s work for any number of years.

In Reinhart Jud’s 1993 Demon Dog of Crime Fiction documentary, Ellroy, riding high on the then-newly published conclusion to his L.A. Quartet, White Jazz, left no one in uncertainty about how he views film versions of his books: “People option my books, they tell me ‘it’s going to be a masterpiece, so and so will direct, so and so will star in it,’ and I say to all of them except James B. Harris, [director of the 1988 James Woods film Cop, a forgettable take on Ellroy’s Blood on the Moon, with Woods as Lloyd Hopkins] HORSE SHIT! Don’t tell me it’s gonna get made, ‘cause it’s not gonna get made, and chances are if you do make it, you’re gonna fuck it up!”

This skepticism is perfectly consistent with Ellroy’s constant warnings that nothing is ever what it seems in Hollywood, and all is not right; in a phrase, disingenuous verisimilitude, a concept pervading literally every one of Ellroy’s books.

While Ellroy’s books have exposed Hollywood’s flaws with candor and unfettered honesty, he is hardly the only novelist to speak critically of Tinsel Town. I remember seeing a 1990s television interview with Michael Crichton, in which The Andromeda Strain author lambasted Hollywood as “a business of idiots!” (An astonishing statement, given Crichton’s decades-long friendship with a certain Hollywood A-lister named Steven Spielberg.) And it’s hard to forget Tom Clancy’s famous quote that “giving your novel to Hollywood is like turning your daughter over to a pimp.”

Curtis Hanson’s 1997 star-studded and Academy Award-winning adaptation of L.A. Confidential recently marked its 20th anniversary earlier this year. Even after two decades, the film is still the best, and most memorable Ellroy adaptation to date. (Please forget about over-rated auteur Brian DePalma’s $50 million defecational flop The Black Dahlia in 2006—just forget about it…)

In a making-of featurette attached to an early DVD of L.A. Confidential, Hanson said of the ensemble cast “My hope was to cast actors that the audience didn’t already know… Actors the audience could discover the way I had discovered them.” Both Russell Crowe (Bud White) and Guy Pearce (Ed Exley) were relative unknowns in 1997. For “Trashcan” Jack Vincennes, Hanson chose an established movie star then at the top of his game: The recently disgraced Kevin Spacey.

The 2001 Ellroy documentary Feast of Death begins with Ellroy’s declaration that “L.A. Confidential the movie is the best thing that happened in my career that I had absolutely nothing to do with… It was a fluke, a wonderful one, and it is never going to happen again, a movie of that quality.” Ellroy then tells of a now-famous encounter with an old lady at a Kansas video store that serves as a parable for the Demon Dog’s assessment of Hollywood. My book, your movie.

Curtis Hanson’s film L.A. Confidential, covering maybe 13% of the book (and roughly four of the novel’s 14 fully developed plotlines), is now 20 years old, and people can’t stop talking about it. By contrast, James Ellroy’s far more cinematic novel turned 20 in June, 2010, and no one, save for Ellroy himself, and maybe the Demon Dog’s publishers, said a word.

I’ve already told you about the disgust I felt over how Hollywood disingenuously treated my favorite character from the novel, rape victim Inez Soto. When I’ve mentioned this to Ellroy on several occasions in the past, he constantly reminds me that the actress who played Inez Soto in the movie, Marisol Padilla Sanchez, is now 44, and too old for me. I insist that I’m referring to the far more richly detailed character from the Demon Dog’s novel, but to no avail. This sardonically humorous exchange between Ellroy and I, coming across like a jazz refrain, makes an appropriate metaphor for the fatuous deference popular culture will blindly pile onto a film, while diminishing, ignoring and eventually forgetting its original inspiration or source. Ellroy is a master of nuance both on the page and in person, and I can’t help but wonder if this dismissive and odd constant response isn’t his allegorical indictment of mass-market disregard.

Introducing a film screening of L.A. Confidential is nothing new for the Demon Dog; he’s done it on countless occasions all over the world—most recently in Chicago in August, 2017. When Ellroy moved to Denver, Colorado in 2015 and began hosting his dynamite and award-winning monthly film series In A Lonely Place, he kicked off the series in September of that year with L.A. Confidential.

Introducing a film screening of L.A. Confidential is nothing new for the Demon Dog; he’s done it on countless occasions all over the world—most recently in Chicago in August, 2017. When Ellroy moved to Denver, Colorado in 2015 and began hosting his dynamite and award-winning monthly film series In A Lonely Place, he kicked off the series in September of that year with L.A. Confidential.

On Monday, December 11, 2017, Ellroy screened a scratchy, off-color 35 mm of his greatest film adaptation (a most non-digital print looking every day of its 20 years) once more, in honor of its 20th anniversary. With a hefty ticket price that included a copy of Ellroy’s latest novel Perfidia, courtesy of the Tattered Cover Book Store, a legendary Denver institution, the crowd was enormous.

After serenading the audience with a hilariously profane Christmas greeting Ellroy termed “Rudolph the Red Nosed Junkie,” Ellroy segued seamlessly into his timeless “peepers, prowlers, panty-sniffers…” intro and a lengthy recitation of T.S. Elliot’s poem “Four Quartets,” in short, a classic Ellroy introduction.

“L.A. Confidential the movie is an extraordinarily witty and lively depiction of L.A. in the 1950s,” Ellroy began. “It’s not a perfect motion picture, but it makes scandal-rag journalism, and the Sid Hudgens character, played by Danny Devito, fun… It makes the ruining of reputations and the American idiom—who’s a homo? who’s a lesbo? who’s a nympho? who’s a dipso? who fucks black people?—fun.”

This largely positive preamble soon gave way to Ellroy’s razor-sharp criticism. “[L.A. Confidential] is somewhat over-rated… It’s better than the over-rated Chinatown, but markedly over-praised.” Ellroy then railed quite loudly against the film’s “BAD miscasting,” declaring that “You feel nothing for Kevin Spacey, and you feel less than nothing for Russell Crowe and Kim Basinger.”

When Ellroy was asked whom he would cast if given free reign, he didn’t hesitate for a second: “A 1982 William Hurt as Ed Exley… Steve Cochran as Jack Vincennes… Sterling Hayden as Bud White [Crowe has actually cited Hayden’s performance in Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing as a model for the Aussie’s performance as White]… and a 50-year-old Albert Finney as Dudley Smith.”

The most titanic irony of L.A. Confidential is that Ellroy wrote the novel with the specific aim to make it as cinema-unfriendly and unadaptable as possible. In an unwitting mockery of Ellroy’s efforts, the film would go on to win an Academy Award for—go figure—Best Adapted Screenplay. And while this is a well-known piece of history among the Demon Dog’s most devoted fans, Ellroy once again related the story of his novel’s bewildering journey to the silver screen, concluding with the warning that “If you write novels to be adapted into movies, you’ll always be on welfare…”

The most titanic irony of L.A. Confidential is that Ellroy wrote the novel with the specific aim to make it as cinema-unfriendly and unadaptable as possible. In an unwitting mockery of Ellroy’s efforts, the film would go on to win an Academy Award for—go figure—Best Adapted Screenplay. And while this is a well-known piece of history among the Demon Dog’s most devoted fans, Ellroy once again related the story of his novel’s bewildering journey to the silver screen, concluding with the warning that “If you write novels to be adapted into movies, you’ll always be on welfare…”

L.A. Confidential’s occasional bouts of anachronistically contemporary dialogue—particularly its Leathal Weapon-quality banter between Crowe and Pearce (Good cop, bad cop in 1953? Really?)—make it difficult to take the film seriously. However, the timing of this watershed anniversary couldn’t be more apropos, as it runs concurrent to a real world metastatic scandal that vibes paranoia like the best of Ellroy’s plotlines: The McCarthy-esque sexual assault malaise currently eviscerating Hollywood and the mainstream media, (indistinguishable entities as far as I’m concerned) and ruining plenty of reputations.

With Kevin Spacey in the dubious cross hairs of the on-going scandal, it was impossible not to talk about him. Ellroy handled the delicate matter with superb rectitude and equanimity: “I will not comment on the trouble that [Spacey] is currently embroiled in, except to say I could’ve predicted it!”

As a new high profile target emerges on an almost weekly basis, this “new McCarthyism” calls to mind the countless allusions Ellroy has made throughout his work to the ruthless sexploitation lurking behind the façade of Hollywood glamour. (Anyone remember the title of the Tijuana stag film Betty Short is coerced into in The Black Dahlia? It’s Slave Girls in Hell…Do you need another reminder?)

Juxtaposed against the scandal itself, Ellroy’s nuanced remark about Spacey deserves further scrutiny… Is Ellroy referring to a personal dislike of Spacey, or the Demon Dog’s career-defining fictional exposure of Hollywood’s pervasive dark side? As always with Ellroy, the answers are illusive and elliptical.

L.A. Confidential is indeed a uniquely prescient film for these dark times, even if it’s 20 years old.

For what it’s worth, happy 20th , L.A. Confidential. I was 16 years old when the film debuted and just two years into my Ellrovian Journey. I loved the film then, and I still love it now, but I’ll take Raymond Dieterling, Wee Willie Wennerholm, Kathy Janeway, and Dream-A-Dreamland (none of which were featured in the movie) any day over “Rollo Tomasi”.

I believe the words of demented patriarch Emmett Sprague from The Black Dahlia are especially relevant right now: “Hearty fare breeds hearty people…”

Skip the movie and read the book.

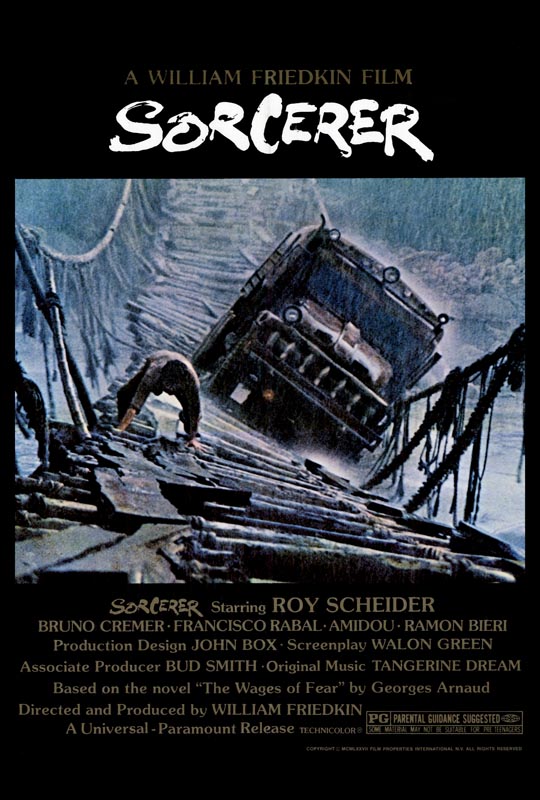

Last Sunday, I had the honour of introducing Sorcerer at Fact cinema in Liverpool. It was a somewhat nerve-wracking experience, not for the public-speaking aspect, which I enjoy, but at the thought that the audience wouldn’t like the film. After all, Sorcerer was a critical and commercial failure when it was released theatrically forty years ago, bringing to an end the tremendous hot streak director William Friedkin had enjoyed with the back to back success of The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973), and it arguably brought about an end to the New Hollywood era itself– that brief but wonderfully rich period in the 1970s when writers and directors had great sway in the studio system and it was relatively easy for them to tell the stories they wanted to tell and get their films made.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself, if your unfamiliar with Sorcerer, let me tell you a little about the plot. A remake of the French film The Wages of Fear (1953), Sorcerer concerns four desperate men who, for varying reasons, are all on the run and find themselves in the Latin American village Porvenir. We have Jackie Scanlon (Roy Scheider) a member of the Irish-American Mob who robbed a rival Mafia Boss and wounded his brother. Then there is Victor Manzon (Bruno Cremer), a French investment banker whose involvement in a massive embezzlement scandal led to a suicide in the family. Kassem (played by Moroccan actor Amidou) is a Palestinian terrorist on the run after blowing up an Israeli bank, and then finally there is the hitman Nilo (Francisco Rabal), of whom the audience is told very little. In the prologue, Nilo commits a contract killing in Veracruz, before heading to Porvenir to lay low, but he remains an enigma throughout. With its poverty, rampant disease and generally squalid living conditions, Porvenir might be described as Hell on earth but it’s actually closer to Purgatory. None of the characters are able to leave, as without money, it is impossible to escape the remote location. An oil well fire offers a potential escape. The only way the fire can be extinguished is to use dynamite, but the nitroglycerine in the dynamite owned by the American oil company is old and leaking and will need to be transported through two hundred miles of jungle. Scanlon, Manzon, Kassem and Nilo are eventually selected to drive the dynamite in two trucks, Lazaro and Sorcerer, to the oil well. Only the promise of high pay and a ticket out of Porvenir would prompt these desperate men to take on such a dangerous job as every jolt or movement on the treacherous roads and jungle foliage they have to traverse could potentially trigger the dynamite to explode.

Their journey starts about halfway through the film, and that’s when the suspense, which had already been creeping upwards in a tense first half, becomes almost unbearable. The highlight is the rope bridge scene, where the two trucks have to be driven across a crumbling rope bridge in the most appalling weather. It’s an excruciatingly tense scene, and a marvel of innovative filmmaking which looks especially good today as audiences have become inured to CGI effects. Friedkin was renowned for taking dangerous risks for making his scenes as realistic as possible. The rope bridge was constructed in the Dominican Republic, where most of the film was shot. But during filming the water-levels of the river the bridge crosses started to go down, robbing Friedkin of the desired effect. The bridge was deconstructed, transported to and then reconstructed in Mexico at a cost of around three million dollars.

In addition to several stunning set-pieces, the acting and direction are also superb. Scheider is brilliant as Scanlon. Despite his role as a failed mobster, he is the everyman who guides us through this journey and projects a sense of humanity that we cling to in a relentlessly bleak film. And yet the film seems to find a humanity in every character: Manzon sincerely loves his wife despite his greed and venality; Kassem has a strong sense of loyalty and friendship, and even the quiet-lipped hitman Nilo is able to generate some sympathy. This is what sets apart Sorcerer from The Wages of Fear (which is a brilliant film in many respects). In the original, we don’t get the prologue scenes explaining why the four protagonists have ended up in Porvenir. While these scenes are brutal, they give the audience empathy for the characters as we get a better sense of their violent, desperate lives. I also think the ending to Sorcerer is superior to how The Wages of Fear ends. Without giving the game away, the ending to Sorcerer relates to how fate dogs our every move.

Friedkin has claimed (among numerous explanations he has given for the choice of title) that as a Sorcerer is a form of malevolent wizard then fate is the Sorcerer in this narrative and this justifies both the title and the gloomy tone. However, audiences at the time assumed that as this was the director’s follow-up to The Exorcist then it must be another supernatural horror movie. But Sorcerer is very different in tone to The Exorcist. It presents a brutally naturalistic world in which men, exiled from their urban environment, find that nature is indifferent to their need to survive.

Another factor that caused the movie to lose box-office potential was Friedkin’s inability to cast Steve McQueen in the lead role. McQueen loved the script, but Friedkin refused McQueen’s request to create a role for this then-wife Ali MacGraw so that they wouldn’t have to be apart for several months. Friedkin would come to regret his stubbornness, realising that McQueen’s name above the title would have lured audiences in. As a side-note, read Friedkin’s memoir The Friedkin Connection (2013): it’s one of the most contrite autobiographies I’ve ever come across by a Hollywood figure with so many achievements to his name, and he certainly owns up to the mistakes he made which lead the film to lose money. Roy Scheider, hot off the success of Jaws (1975), was cast at the producers insistence. Despite having worked together before on The French Connection, there was tension between Scheider and Friedkin as Friedkin had rejected the actor for the role of Father Karras in The Exorcist. Scheider’s casting led to a tense set. But finally, the biggest factor which lead to the failure of the film was that it was released around the same time as Star Wars which broke all box-office records and led to a slew of sci-fi imitators. By contrast, Sorcerer recouped less than half of its budget.

Three years after the release of Sorcerer, Michael Cinimo’s historical epic Heaven’s Gate was released in cinemas and received a shellacking from critics and disastrous box-office returns. Cinimo, briefly a darling of the critics after directing the oscar-winning The Deer Hunter (1978), had been indulged every whim by the studios eager for him to repeat his success and create a modern-day Gone With the Wind but it all went horribly wrong. If Sorcerer signalled the end of the New Hollywood period, then the failure of Heaven’s Gate only confirmed it. Studio executives regained full influence by the 1980s, and their grip has only tightened over the years as seen with the dreary repetitions of franchise reboots, remakes and re-imaginings. Now there are some critics who have argued that Heaven’s Gate is a neglected masterpiece. Frankly, I think that film may have deserved its critical drubbing, but I do believe that Sorcerer was unfairly maligned by reviewers upon its initial release. Fortunately, its reputation has grown over the years. Stephen King has named it as his favourite movie; Quentin Tarantino is a big fan, and film critic and Friedkin expert Mark Kermode has championed its re-release. As for the audience at FACT Liverpool that day, well I said in my intro that if anyone didn’t like it they were free to harangue me in the bar afterwards. I needn’t have worried, as there was nothing but positive feedback. If anyone didn’t like it, they kept it to themselves. But don’t take my word for it, a special edition Bluray DVD has been released to mark the fortieth anniversary of the film, so it will finally reach the wide audience it deserves. Sorcerer has taken a while to weave its magic, but it now stands out as one of the best films of the 1970s.

Maybe it was fated to be a hit after all.

Sorcerer at FACT Liverpool December 3rd

Excellent news! Sorcerer will now play at FACT cinema in Liverpool on December 3rd at 12 noon. We sold enough tickets via Ourscreen to make the screening happen, but there are still plenty of tickets available so if you able to attend book your tickets here. I’m going to say a few words before the film and will do a write-up on the blog here afterwards. Thanks to everyone who promoted this via Twitter, Facebook or good old-fashioned word -of- mouth. We’ve generated some great publicity, and there are now screenings of Sorcerer planned in Oxford, Derby, Norwich and York. These screenings won’t go ahead unless enough tickets are sold, so if you live close by book now via Ourscreen.

Incidentally, my good friend Dan Slattery has set up a Christmas screening of Die Hard at FACT cinema, Liverpool for December 23rd. It’s one of my favourite Christmas movies but I’ve never seen it on the big screen before, so I’ll be attending. Book here if you can come.

And here’s the nation’s favourite film critic, and William Friedkin expert, Mark Kermode discussing the audience’s response to the recent 40th anniversary re-release of Sorcerer:

William Friedkin’s Sorcerer at FACT Liverpool

It has been forty years since William Friedkin’s seminal thriller Sorcerer was released in cinemas. Overshadowed at the time of its release due, in part, to the tremendous success of Star Wars and the sci-fi craze it created Sorcerer is now regarded as a classic thriller, and has been cited by such figures as novelist Stephen King, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino and critic Mark Kermode as one of the greatest films ever made. To mark the anniversary it is being shown in selected cinemas in the UK. There wasn’t a showing planned at my local cinema FACT in Liverpool so I contacted the team at OurScreen and arranged a showing. Sorcerer will be playing at FACT Liverpool on December 3rd at 12 noon providing enough people book ahead. The bookings need to have been made online by October 29th or the showing won’t go ahead. Hopefully we’ll get enough bookings and if you’re interested and live locally enough do please come. I’ll do a review of the film on the blog afterwards. Here’s the link where you make the booking on OurScreen.

And here’s the trailer to the film:

Wartime James Bond

The James Bond film series has always tried to move with the times, not just by embracing new styles of film-making but also by updating the political context. As such, the films have long since abandoned the idea that Bond was a Cold-War warrior. The espionage conflict between East and West was, to varying degrees, the backdrop to every Bond film from Dr No (1962) to Licence to Kill (1989). The first film of the series I saw in the cinema, Goldeneye (1995), at least acknowledged Bond was a Cold War veteran adjusting to the new threats the world was facing. But since then, the Cold War has faded from the consciousness of the recent Bond films and their younger viewers.

It should be noted that the Cold War setting of the early films was a direct consequence of a much hotter conflict – the Second World War. It’s striking how many of the key players of the early Bond series were veterans of the conflict. Fleming, like his fictional counterpart, was a Commander in the Royal Navy during the war and Bond was a composite of several RN Commandos who were in his charge. Fleming formed his band of ‘Red Indians’, 30 Assault Unit who performed daredevil missions during the conflict, although the future author saw little, if any, combat himself. Terence Young, who directed three of the first four James Bond films, was a tank commander who saw action in Operation Market Garden. Legendary art director Ken Adam, who gave the Bond sets their unique and epic look, was a German-born RAF fighter pilot. In his memoirs, Roger Moore recalled witnessing a V1 Doodlebug land on the streets of London.

The Second World War was always a lurking presence in Fleming’s Cold War thrillers. In this post, I am going to connect some moments from the Bond film and literary series to events from the war. Let’s start with Fleming’s debut novel Casino Royale (1953). In it, Bond plays a high stakes baccaret game against the villainous Le Chiffe. Fleming claimed to have based the showdown on an incident from the war where Fleming played baccaret against German agents at a casino in Lisbon, although, in his biography of Fleming, Andrew Lycett claims it is more likely Fleming got the idea from a number of wartime incidents involving other allied agents:

Ian and (John) Godfrey took the usual roundabout air-route from Britain – KLM to Lisbon and then Pan Am to New York via the Azores and Bermuda. They stayed a couple of nights in the big Palacio Hotel on the Tagus estuary at Estoril, where one of the more heavily embellished incidents in Ian’s wartime career took place. After dinner the second night, Ian wanted to play at the casino, a favourite pre-war pursuit which he had recently been denied. It was a sombre and uneventful evening in a dim-lit building. His fellow gamblers were Portugese businessmen in suits. The stakes were not particularly high, and Ian lost. As he was leaving the gaming tables, he turned to Godfrey and, with a touch of imaginative genius, tried to invest the drab proceedings with some spurious glamour: “What if those men had been German secret service agents and suppose we had cleaned them out of their money; now that would have been exciting.” […] But others have also claimed responsibility for this incident, or something like it. One was Dusko Popov, the Yugoslav double agent who worked for the British while pretending to spy for the Germans. Popov gave the British secret service an opportunity to “play back” some of the false information it wanted the Nazis to hear. Another was Ralph Iard, a fellow member of NID, who played roulette with a group of expatriate Nazis in Lisbon while he was en route to South America on a wartime mission. Iard later recalled how Ian had been very interested in his story.

And here is the climax of the card game, brilliantly dramatised in the 2006 film adaptation of Casino Royale (Baccaret was switched to Texas Holdem in the film):

The Soviet spy agency Smersh features prominently in a number of Fleming’s novels. They are portrayed as Bond’s counterparts and nemesis in Russian Intelligence, leading the fight against the decadent West. In reality, Smersh was founded by the Russians during the Second World War. After Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, a massive land invasion of the Soviet Union, the initial success of their campaign led to widespread desertion and surrender in the Russian military. Smersh was formed as an umbrella organisation of the existing Soviet Intelligence services to subvert German attempts to infiltrate the Red Army on the Eastern Front. In an article for the Journal of Contemporary History, the historian Robert Stephan suggests that the name Smersh came from Stalin himself:

According to a Soviet history of the Special Departments, there were several suggestions at a meeting with Stalin of names for the new organization. One of the suggestions was Smernesh, or Smert’ nemetskim shpionam (‘Death to German Spies’). Stalin replied: ‘And why as a matter of fact should we be speaking only of German spies? Aren’t other intelligence services working against our country? Let’s call it Smert’ Shpionam.’ Hence the name ‘Death to Spies’.

After Germany’s surrender in 1945, the duties of Smersh were transferred back to NKGB the following year and the organisation essentially ceased to exist, but Fleming found their brutal counter-intelligence methods memorable enough to make them a major Cold War presence in his fiction. In Casino Royale, Le Chiffre is the paymaster of a Smersh controlled trade union, and a Smersh agent engraves a Cyrillic mark into Bond’s hand so that other Smersh agents will recognise him as a spy. Smersh would continue to feature in Fleming novels such as From Russia With Love (1957) and Goldfinger (1959), but in the film series they feature less prominently as the colourful SPECTRE (SPecial Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion), which featured in all but one of the Sean Connery Bond films, seemed more suited to the outlandishness of the Swinging Sixties. Smersh still plays a major role in the film adaptation of From Russia With Love (1963), and more elliptically in 1987’s The Living Daylights, one of the strongest entries in the series and the last to be truly about the Cold War, where two MI6 agents are murdered with the message Smert’ Shpionam left by their corpse.

My final example is a bit more debatable in terms of the influence of World War Two. Author Jeremy Duns has claimed the pre-credits sequence of Goldfinger (1964) was inspired by an Allied Intelligence mission in which a Dutch spy was smuggled into Nazi-occupied Netherlands. The scene in the film is set in an unnamed South American country, Bond is first seen emerging from the water in a wet-suit wearing a fake duck on his head before covertly entering a drugs laboratory and planting some explosives set to a timer. He slips out of the wet-suit, revealing he’s wearing a perfect white tuxedo beneath and makes his way to a nearby tavern in which nearly all of the occupants clear out of in a panic when they hear the nearby laboratory erupting in flames. Bond stays to seduce a dancer, but they’re steamy encounter is interrupted by a local heavy who tries to knock out Bond with a cosh. After a fight between the two, Bond finishes the villain off by shoving him in a bath and throwing an electric light in the water. ‘Shocking’, Bond quips before leaving to catch his flight to Miami where the main plot of the film begins.

Stirring stuff, but what has it possibly got in common with the grim realities of a World War Two spy mission? Well Duns makes a convincing case that the scene was based on the ‘Scheveningen’ mission in which Peter Tazelaar was tasked by the Dutch Government-in-exile to covertly land ashore at Scheveningen in his then occupied home-country, and find and extract two Dutch agents and bring them back to safety in Britain:

Their plan was simple but audacious – approach Scheveningen in darkness by boat, and take Mr Tazelaar into the surf by dinghy, from where he could scramble ashore. Once there, he would strip off his wetsuit, to reveal his evening clothes underneath, to enable him to pose as a partygoer and slip past the sentries.

The operation began fairly well. Tazelaar disembarked from a British Motor Gun Boat into a small dinghy. Once ashore, he slipped out of a specially designed wet-suit under which he was wearing immaculate party clothes, and staggered, feigning drunkenness, past two unsuspecting German sentries nearby. On a later date though he was picked up on the same beach by the Gestapo and taken in for questioning but, cool under pressure, managed to bluff his way out by claiming to be a drunken reveller. The mission was ultimately blown, and while Tazelaar managed to escape he was unable to bring back the two agents.

Whether the opening scene of Goldfinger was based on the exploits of Tazelaar it is hard to say. The scene is a creative reworking of the first chapter of the novel which begins with Bond nursing a double bourbon at the departure lounge of Miami airport, and feeling somewhat grubby after being forced to kill a Capungo, Mexican bandit, who was a part of the opium smuggling ring Bond had been assigned to smash. The scene is a typically strong opening to a Bond novel, and incidentally was cited by Roger Moore as a major influence in his portrayal of the character, but it has more to do with Fleming’s lifelong fascination with the process of smuggling than his or anyone else’s experiences during wartime. There is no wet-suit hiding an impeccable tux in the book; however, Duns argues that so many of the key players in the production of Goldfinger had Intelligence experience during wartime that a knowledge of the Scheveningen mission could have easily slipped into the script. The screenplay to Goldfinger was co-written by Paul Dehn who had been a Special Operations Executive officer during the war, and the film was directed by Guy Hamilton who had served in the Royal Navy’s 15th Motor Gunboat Flotilla and had been involved in missions landing MI6 agents on the coastlines of occupied Europe.

Whether or not it was directly based on the Scheveningen mission, the opening to Goldfinger is a great scene which did much to set the formula of the pre-credits sequence being a mini-movie in itself, and the influence of the Second World War on the Bond novel and film series should not be underestimated or ignored.

The North and Romantic Fatalism in the work of David Peace

The latest issue of the British Politics Review takes a look at the political and cultural landscape of the North of England. When I was asked to contribute an article I was a little hesitant. Despite being born in Chester, and working in Liverpool I’ve never felt particularly Northern. But then I decided I have as much right to call myself Northern as anyone else, so I put together a piece which examines the great crime novels of Yorkshireman David Peace, and throws in some of my observations about the North. The article is called ‘The North and Romantic Fatalism in the work of David Peace’, and you can read the entire issue here.