Terence Young – The Man Who Would Be Bond

Terence Young is remembered today as the director of three of the first four James Bond films: Dr No (1962), From Russia With Love (1963), and Thunderball (1965). The rest of his directing career was mixed: some genuinely good films, Wait Until Dark (1967) and Mayerling (1968), and many other films that were mediocre at best. Young himself is fascinating figure, but no biography has ever been written of him (although there is one Italian monograph which is a study of his films). However, he seems to pop up as a colourful character in the biographies of several famous figures. It was not until I read Ben Macintyre’s excellent Agent Zigzag (2007), about the extraordinary life of MI5’s wartime double agent and criminal Eddie Chapman, that I learned that Young worked with British Intelligence during the Second World War. Young was an intelligence officer attached to the Field Security Section of the Guards Armoured Division which saw heavy fighting at Normandy and Arnhem.

Young counted Eddie Chapman as a friend before the war. Young had a reputation as a sophisticated gentleman with a taste for fine wine, expensive clothes and beautiful women. Chapman, on the other hand, was involved with criminal gangs and was an expert safecracker. The two men’s paths crossed in London where the division between high society and the criminal underworld was not always distinct at the time. Macintyre describes the remarkable series of events that followed: Chapman was serving a prison sentence on the Channel Islands when it came under Nazi occupation. He was transferred to a prison in Paris when he offered his services to the Abwehr, German Intelligence. After being parachuted into England as a German spy, he immediately contacted MI5 in the hope of working for them as a double agent. Young was contacted by Intelligence agent Laurie Marshall to meet with his old friend Chapman and ‘build up his morale’. Young was glad to do this, and he also provided a character reference for Chapman saying he would make a perfect spy:

Young went on to describe the glamourous, roué world Chapman had inhabited before the war, the people he knew from ‘the film, theatrical, literary, and semi-political and diplomatic worlds’, and his popularity, ‘especially among women’. Could Chapman be trusted with intelligence work, Marshall inquired? Young was adamant: ‘One could give him the most difficult of missions knowing that he would carry it out and that he would never betray the official who sent him, but that it was highly probable that he would, incidentally, rob the official who sent him out… He would then carry out his [mission] and return to the official whom he had robbed to report.’ In short, he could be relied on to do whatever was asked of him, while being utterly untrustworthy in almost every other respect.

Young’s assessment of Chapman proved to be highly accurate. Young’s insight and experience into the real world of espionage must have surely influenced his contribution to the success of the James Bond films, just as Ian Fleming’s experiences in Naval Intelligence influenced his creation of Bond, even though the character inhabits a fantasy version of the world of a spy. Young also gave the cinematic James Bond facets of his own character. In an essay written for Her Majesty’s Secret Servant, Robert Cotton examines how Young schooled Sean Connery on how to be Bond:

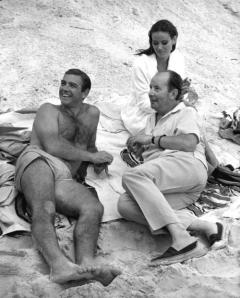

When Connery arrived, far before filming began, Young saw his best opportunity to mold the actor in his own image. As Lois Maxwell related in one of Connery´s many biographies, “Terence took Sean under his wing. He took him to dinner, showed him how to walk, how to talk, even how to eat.’ Some cast members remarked that Connery was simply doing a Terence Young impression, but Young and Connery knew they were on the right track. Then, late in pre-production, when Connery was almost ready to make his debut, Young took Connery on a lunchtime trip into downtown London, to his own tailor on Saville Row. It was time for Connery to “put on the suit’ as it were. It was time for Connery to become James Bond.

By the time Connery showed up for his first days filming, Young had changed everything about him. Connery no longer talked with his hands, one of Young´s most infamous pet peeves. He still moved perfectly, but Young had coached him on WHEN to move. Connery was already far from being a hack actor when he came to the series, but Young knew how to make Connery shine, and he did. Young had taken elements of his own personality and passed them on to Connery. He had turned Connery into a gentleman, and then he turned that gentleman into James Bond.

It’s a shame that having played such a big part in the success of the Bond films that the rest of Young’s work would not be so distinguished. He directed a highly fictionalised and rather disappointing film about Eddie Chapman’s wartime adventures, Triple Cross (1967), and has the dubious distinction of directing what is generally regarded as one of the worst films of all time Inchon (1982). An epic retelling of the Korean War battle, Inchon was partly financed by Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon and starred, in a terrible piece of miscasting, Sir Laurence Olivier as General Douglas MacArthur.

Terence Young died in 1994, and because his reputation had steadily declined with each poorly received film, it is perhaps not surprising that he is largely forgotten today. But several years ago an intriguing rumour began to circulate on the internet. In the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by Coalition forces an article written by Mark Bowden titled ‘Tales of the Tyrant’ appeared in The Atlantic. Bowden presented a rather distasteful, fawning portrayal of Saddam Hussein and briefly stated that Terence Young had edited the film The Long Days (1980), a propaganda piece about Saddam’s early life. The claim was later repeated in the play It Felt Like a Kiss (2009), and is examined in this online essay, but on Young’s imdb page, his involvement is listed ‘uncredited’ and ‘unconfirmed’. Even so, its remarkable to think that Young may have still been involved in a murky world of intrigue at that late stage of his life and career. If the rumour is true, it is a stain on Young’s reputation, especially considering that Young often appeared to be a patriot with a social conscience, having directed the anti-drugs trade film The Poppy is Also a Flower (1966), financed by the United Nations. The film may have been made before the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War, but the brutality of Saddam’s regime would have still been clearly evident. In the film, Saddam was played by his cousin Saddam Kamel, who was later killed on the dictator’s orders.

Regardless of this rumour, Young will be best remembered for shaping the cinematic character of one of our best loved spies.

Update: I’ve discovered new information on Young which I’ve put in a follow-up post ‘Where is Parsifal and the Continued Enigma of Terence Young’.

Trackbacks

- Where is Parsifal and the Continued Enigma of Terence Young « The Venetian Vase

- Parsifal Found! | The Venetian Vase

- Kay Mander | What's On Scotland

- Kay Mander obituary | Tech Auntie

- Bond Directors at their Best | The Venetian Vase

- Dr. No – Lo bloc

- THE VALACHI PAPERS: Godfather Lite? -

- Wartime James Bond | The Venetian Vase

- The Tortured Production of Tai-Pan | The Venetian Vase

- Remembering Sean Connery: A Tribute to a Legend Who Launched the James Bond Franchise - Hollywood Insider

Hi there. The claim that Terrance Young helped on The Long Days comes from Said K. Aburish’s biography of Saddam Hussain. Aburish hired Young when Iraqi TV asked for a notable western filmmaker to give their production some legitimacy. The film was only shown in Iraq.

Faisal,

Thank you so much for this information. I wonder if there is an English language edition of Aburish’s biography as I would like to read it. My late father had the Conn Coughlin bio of Saddam and I should really try and get hold of that too!

Steve

Young really established Bond with the three films. For a long time afterwards, everyone else was just copying his work. While Bond films did start breaking away from the Young format in the 1990s, they still owe a great debt to the man.

Thanks for dropping by and commenting. The more I read about Terence Young the more I am impressed by his accomplishments. But it only makes his career decline seem so regrettable. He made bad choices, as with ‘Inchon’ and the Saddam flick, but it also seems he was unlucky. ‘The Klansman’ had potential but it was hampered by a chaotic production as Lee Marvin and Richard Burton were blind drunk for much of the shoot and either din’t show up or were unable to work.

Is it possible that after his early success he was trying to take risks? He had to know the Saddam flick was dangerous and that Marvin and Burton were difficult. It is a shame.

Defintely. Young was said to have turned down the chance to return to the Bond films and direct ‘For Your Eyes Only’ which was a surefire hit. He took risks with occasionally bizarre projects. If you haven’t read it yet, here’s my take on the oddball film ‘Where is Parsifal’