On re-watching all the 007 films on the big screen, in 4K

Today’s guest post is by Craig McDonald, author of the superlative Hector Lassiter series of novels.

This summer, I’ve been privileged to savor what’s been billed as a revolutionary, world-exclusive Bonding experience.

The very cutting-edge Gateway Film Center located on The Ohio State University campus has been presenting, “For the first time ever, all 26 James Bond films in order of release, restored in crystal clear 4K!”

That’s right: starting back on July 1 with 1962’s Doctor NO, and every fourth day since, a subsequent “classic” Bond film has been screened at a level of visual and audio quality far eclipsing that of the ABC Sunday Night Movie versions I grew up on in the late-1960s and early-1970s, or even the films I saw upon first-release on the big screen starting with (here I date myself as cinema Bond and I came into the world together in 1962) You Only Live Twice, at the tender age of five.

Hell, the quality of this summer’s large-screen 007 versions are light years beyond that of any of the remastered VHS tapes or DVD’s I’ve bought in the many years since.

As a James Bond aficionado and a novelist who not so long ago published his own 007 pastiche (Death in the Face, Betimes Books, October 2015), this summer’s film series has proven impossible to pass up.

Confession here: I didn’t see all 26 films. To get to that count, Gateway incorporated two non-Eon productions, the rogue Connery comeback and Thunderball remake Never Say Never Again —a did-see re-watch, and quite stunning in restoration; a superior film in every retrospective respect to the then-competing Octopussy, which is a lukewarm mostly Goldfinger-remake—and the original Charles Feldman-version of Casino Royale, which after a one-time viewing about thirty years ago, I swore off forever.

(Sometimes we say never again, and we goddamn mean it.)

Scattered visceral impressions:

Scattered visceral impressions:

The early Bond films, particularly Doctor No, are exceptionally stunning in these big-screen, digitally remastered renditions. All should be so lucky to have this experience: Every crease of Bernard Lee’s suit jacket and forehead wrinkles in his icy first scenes as “M” are stunningly sharp in NO, as are the beads of sweat on Connery’s forehead during that tarantula scene.

The cinematography of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the only of the non-Feldman Bond film I’d never seen on the big screen before, is strikingly edgy and beautiful, particularly in its opening, haunted pre-titles scenes set on a beach at sunset, and during the twilight ski chase down from Piz Gloria.

On that note, you also really have to see these films on the big screen in 4K to truly re-appreciate the framing of all of their exotic settings that surely enchanted and remained impossible fantasy destinations for the films’ then mostly middle-income fans across their 20th Century releases.

Last scattered impression: Despite its rogue status, Connery’s swan-song, NSNA, clearly shaped subsequent EON Bonds, from its black Felix Leiter, to Barbara Carrera’s obvious inspiration for Famke Janssen’s Xenia Onatopp and its more grounded chief villain.

But seeing these films writ large and in tight compression this way also reminded me of many unhappy and aggravating earlier experiences and frustrations experienced during long-ago, first-run viewings throughout the 1970s and early-1980s.

For me, the Roger Moore films were nearly unendurable in real time, back-when.

Outside of his debut in Live and Let Die, and Sir Roger’s one, somewhat Conneryesque outing in For Your Eyes Only, I truly loathed nearly all of those films, then and now.

For me, Moore’s Bond also dates the most severely, not just in terms of all the wide lapels, fat ties and flared slacks, but far more for Bond’s exceedingly poor — and frequently contemptuous — treatment of women.

Connery’s swaggering machismo and interactions with females (even that crack about “man talk” and subsequent slap at Dink’s backside in Goldfinger) elicited wry and I assume-to-be ironic knowing laughs this summer, this from a mostly college-age and female-skewed audience. (As it happened, I was nearly the only male in the house for Goldfinger, this 4K-enhanced round.)

Connery could surely play the 1960s-era rake, but one gets the sense even half-a-century and more hence, Sean’s is a killer who at-base appreciates women, even if he isn’t always particularly polite to them, or above coldly using them to further aims on a mission as required.

Indeed, in several instances, Connery’s Bond seems truly engaged by and really affectionate toward his female leads, particularly in his first two outings, as well as in his last.

In my revisited take this round, Moore’s Bond once again never seemed honestly affectionate or even mildly kindly-disposed toward any of his leading ladies, not once.

Fleming’s literary Bond often gets bad-rapped (at least in my estimation) for perceived misogyny.

But I’d argue Fleming’s original 007’s interactions with several of his female protagonists firmly contradicts that alleged defect.

In contrast to Moore, Dalton’s and Craig’s Bonds (certainly so in both actors’ first outings) are clearly smitten by — and even actually frequent and charming tools for — their cunning female foils.

I’ll state here that my most consistent companion throughout this summer’s “once-in-a-lifetime” viewing experience has been our now-17-year-old, youngest daughter.

Every generation has its Bond, and her 007 has been Daniel Craig (lucky kid). She appreciates and has real affection for Sean Connery.

Both our daughters came around on George Lazenby upon big-screen viewing of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service this summer.

The youngest also this time came to appreciate Timothy Dalton’s most Flemingesque Bond as a strong and honest foreshadowing of Craig’s current take on 007.

Despite much playing of Nintendo’s Goldeneye on a vintage video console we still have around, neither of our daughters is a Pierce Brosnan fan, not even a little.

And one soundly denounced Moore’s Bond for his manipulation of Solitaire in her summer’s critique of Live and Let Die, and consistently and correctly seized upon that version of Bond’s myriad other abuses of female characters in that film.

Most vintage 007 things hold up quite well, but some now offend.

(Many from the Moore era deeply offend, even eliciting some boos this summer).

Still, I’ll submit it’s impossible for anyone born after even, say, 1975, to grasp how revolutionary and influential the first few Bond films have proven.

Ernest Hemingway claimed all of American literature starts with Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn.

I contend all of post 1962-action cinema — from Star Wars to you name it, springs from Doctor No.

Even now, with enhanced visuals and sound, the machine-gun editing speed and exaggerated sound effects of the Robert Shaw/Sean Connery brawl upon the Orient Express in From Russia With Love constitutes a revolutionary and exhilarating assault on the senses.

John Barry’s scores hold up wonderfully, even during the mostly undistinguished run of Moore era-soundtracks.

(And, please, EON, bring back David Arnold for Bond 25; much as I enjoyed Skyfall and Spectre, I’ve found the soundtracks for both films particularly un-engaging, and even more so, having heard them all again back-to-back these past weeks.)

Last night, we revisited Casino Royale: We’ve at last caught up to 21st-Century cinema James Bond.

The youngest McDonald first saw that film at nearly the same age I saw my first Bond film in 1967.

At seventeen, she got to see it better than she remembered it, in all that “crystal clear 4K.”

To watch it again in that pristine form was, for all of us, a renewed revelation and reminder how much we’ve savored Daniel Craig in the role.

And now EONs’ Bond “25” looms.

God willing, the four of us will see it together again sometime in the fall of 2018, and be enchanted anew.

My favorite Bond elements based squarely on this summer’s “enhanced” big-screen versions:

Bond Films:

- From Russia With Love

- Casino Royale

- On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

- The Living Daylights

Best Soundtrack:

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

Best Bonds:

- Daniel Craig

- Timothy Dalton

- George Lazenby

And in class all his own:

- Sean Connery

Youngest McDonald’s picks:

Best Bond films:

- Casino Royale

- From Russia With Love

- Skyfall

- License to Kill

Best Bonds:

- Sean Connery

- Daniel Craig

- Timothy Dalton

Craig McDonald is the author of the Hector Lassiter series. A graphic novel of his Edgar Award-nominated novel HEAD GAMES will be published by First Second Books on Oct. 24.

Check out my interview with Craig from last year here.

James Ellroy Glossary

In this post our Guest Writer Jason Carter excavates and restores an early companion to the Demon Dog’s work:

James Ellroy has one of the strongest commands of language of anyone I’ve ever encountered, writer or otherwise. I’ve often said that the Demon Dog has personally taught me more about the English language than anyone else. This is partly why I refer to Ellroy unequivocally as my greatest teacher.

James Ellroy has one of the strongest commands of language of anyone I’ve ever encountered, writer or otherwise. I’ve often said that the Demon Dog has personally taught me more about the English language than anyone else. This is partly why I refer to Ellroy unequivocally as my greatest teacher.

I met Ellroy for the very first time, during the Denver stop of his Blood’s A Rover tour in October, 2009, at the Tattered Cover, an iconic independent Denver bookstore. Introducing Ellroy that night, the bookstore’s manager explicitly said that “there are many of us here at the store who believe [Mr. Ellroy] is one of the greatest writers of prose… ever.” (You can listen to a podcast of this introduction, plus Ellroy’s wild presentation that night here)

In Reinhart Jud’s 1993 documentary Demon Dog of Crime Fiction, Ellroy acknowledges that his Lloyd Hopkins trilogy (Blood on the Moon, Because The Night, Suicide Hill) taught him the rudiments of writing, in spite of how emotionally unsatisfying those novels were for him. With his L.A. Quartet novels and a personal challenge to make every successive novel “richer, darker, deeper, more sexed-out, weird and redemptive”, Ellroy would begin his transcendence of linguistic boundaries, and eventual vast expansion of the vocabularic capabilities of language.

Part of this complexity came about, as many discoveries do, as a byproduct of necessity. When Ellroy submitted an 800 page manuscript for L.A. Confidential, his editor asked the Demon Dog to shorten it by 100 pages. Most writers would accomplish this by eliminating a subplot, or even a character. Ellroy instead focused on the book’s language and narration, cutting away unnecessary words, and stripping L.A. Confidential down to a hyper-kinetic shorthand that greatly accelerated the novel’s pace, and ultimately excised more than 200 pages from the original manuscript.

The first draft of White Jazz, written in a normal first person perspective, read flabby and excessive. Ellroy applied his elimination technique to the L.A. Quartet’s concluding volume even more stringently than before, and thus created, in his estimation, “the perfect fever-dream voice for [White Jazz’s narrator] Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klien”.

The 2001 publication of The Cold Six Thousand would push Ellroy’s manic shorthand to its absolute apex, with each sentence stripped to its essence. The effect is simplistic in its singularity, yet at nearly 700 pages in hardcover, pugilistic and densely baroque in its totality. In Ellroy’s 2010 memoir, The Hilliker Curse, he says of The Cold Six Thousand, “I wanted to create a work of art both enormous and coldly perfect… I wanted readers to know that I was superior to all other writers,” while later acknowledging the severe “ass kicking” he and the book received from critics.

The Cold Six Thousand, like many of Ellroy’s latter works, is highly rhetorical, and demands to be read aloud. When I worked in broadcasting several years ago, I would always read an Ellroy chapter or two aloud as a vocal warm-up before my radio show, or even for a long day of recording voice overs for commercials. I wish I had recorded these Ellroy-fueled warm-up sessions; they were quite hilarious.

If you’ve ever seen Ellroy read his work for an audience, you know the Demon Dog practically bellows each sentence. This is primarily because the books themselves are so graphic, in language and content, that to read them in anything but the most powerful tone possible would be a severe and disingenuous injustice. The language is itself an indispensable main character.

A classical music fanatic, Ellroy has infused all his novels with more than a respectful hat tip to his icons, particularly Beethoven. I would easily place Ellroy among a lineup of virtuosos—literary, musical and artistic alike—including Nicolo Paganini, Franz Liszt, Anthony Burgess, Hieronymus Bosch, James Joyce, Art Tatum, and more contemporarily, John Petrucci and Steve Vai. In fact, I once described the Demon Dog to a friend as “crime fiction’s Beethoven painted by Hieronymous Bosch, as told to James Joyce, if all three were tossed into a blender and mixed on frappe.”

Chip Kidd, who has designed the cover art for all of Ellroy’s Alfred A. Knopf-published work, described the Demon Dog as “Mickey Spilane with a master’s degree…except I know that James doesn’t have a master’s degree.”

Introducing Ellroy at the Mystery Writers of America’s 2015 Grand Master ceremony, Mysterious Press owner and early Ellroy mentor Otto Penzler said the Demon Dog’s prose style “is so original, and so powerful, that I wouldn’t hesitate to call [Ellroy] the most influential American writer of the last quarter century.”

Ellroy himself has defined his distinctive style as a “heightened pastiche of jazz slang, cop patois, creative profanity and drug vernacular” with a specific employment of period-appropriate slang. Ellroy elaborated on this in a 2010 interview with TIME Magazine: “I love the hard-boiled school of language,” Ellroy said. “I love scandal language, chiefly alliteration. I love racial invective, I love Yiddish. I love language that is vulgar, that lives on the page.” Anyone who’s experienced an Ellroy novel can certainly confirm that the Demon Dog’s writing is as alive as a rabid pit bull.

The now-defunct fan site Ellroy.com, accessible via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine includes a decent glossary of the countless abbreviations and colloquialisms that abound in the Demon Dog’s cannon. I’d come across this list years ago when the site was still active. Not long ago, I gave Ellroy a printed copy at one of his Denver film screenings. The list is not comprehensive, but it is to date the only Ellroy glossary I’ve ever seen. Also, it’s more beneficial to have it here than relegated to the infinite ash pile of forgotten web pages.

And, this list is arguably one of the first published companions to Ellroy’s work—predating the efforts of both Peter Wolfe and Jim Mancall. Overall, a helpful component to understanding Ellroy’s complex and engrossing literary style.

Feel free to riff on—and possibly expand—this collection.

Here it is, hepcats:

A

ADW-Assault with a Deadly Weapon.

ASAC-Assistant Special Agent in Charge.

B

B&E-Breaking and Entering.

Bad Back Jack-John F. Kennedy.

bagman-a person who collects, carries or distributes illegal payoff money.

bailiwick-jurisdiction.

Beard, The-Fidel Castro.

beef-criminal charge.

Big H-heroin.

Big Q-San Quentin Prison.

(the)big nowhere-death.

blue-a uniformed cop.

bomb-to move quickly.

bombed-drunk.

bonaroo-cool.

bootjack-steal.

boost-steal.

brace-to stop someone for questioning.

brass hat-high-ranking police officer.

bubbkis or bupkis-nothing.

bull-cop.

bullet-one year of prison time.

buttonhole-to grab someone.

C

CO-Commanding Officer.

cheaters-eyeglasses.

chickenhawk-child molester.

cipher-loner.

clout-steal.

collar-conviction.

conk-head or hairdo.

D

DL-Driver’s License.

DT’s-symptoms of alcohol withdrawal (delerium tremens).

dagger-butch lesbian.

ding-mentally ill prisoner.

dink-drug dealer.

Dracula-Howard Hughes.

E

F

FI-Field interview. Police reports regarding the questioning of potential suspects.

finger-a witness prepared to testify against a suspect.

filch-to steal.

firebug-arsonist.

fish-dead body.

4F-draftee rejected for being physically unfit.

(the)fourth estate-the press.

from hunger-very bad or inept.

fur book-pornography.

G

ganef-theif (from the Yiddish)

gash-woman or women (in sexual context).

gelt-money.

glom-pick up; perceive.

goat-caddy.

grok-accuse.

GTA-grand theft auto.

gunsel-armed criminal.

H

(the)Haircut-John F. Kennedy.

Hat Squad (the Hats)-Homicide Division.

harness bull-a uniformed cop.

heister-armed robber.

highball-v. to move quickly. n. a mixed drink; cocktail.

hinky-suspicious.

hink (to)-to become aware of.

hop-a narcotic drug; esp. opium

HUAC-House Un-American Activities Committee.

hype-Heroin addict.

I

IA or IAD-internal affairs department.

J

jack-money.

jacked-high on drugs.

jacket-reputation or police record.

jaw-talk.

jocker-male prostitute.

juice-power.

juicehead-alcoholic.

juke-insult or kill.

K

KA-known associate

kibosh-to put an end to.

kipe-steal.

knosh or nosh-eat.

L

lamster-fugitive from the law.

lox-low brow film.

lubed-drunk.

M

ME-Medical Examiner.

Mickey Finn-a drink of liquor doctored with a purgative or a drug.

MO-Modus Operandi.

N

NMI-No Middle Initial.

O

187-murder.

P

pills-bullets.

PFC-Private First Class.

PO-probation officer.

Q

qt-short for quiet.

quail-attractive woman.

quiff-gay man.

R

raisinjack-potent alcoholic brew made of fermented rasins.

rebop-bullshit.

R&I-;Records and Information department.

roscoe-gun.

roundheels-a promiscuous woman.

roust-arrest.

S

SAC-Special Agent in Charge.

SID-Scientific Investigation Division.

SOP-Standard Operating Procedure.

SRO-Standing Room Only.

sawbuck-ten dollars.

schtup-have sex with.

schvantz-penis.

scoot-a dollar.

scrape-an illegal abortion.

scratch-money.

shakedown-to exort money from.

shill-a person who praises or publicize something or someone for reasons of self-interest.

shitbird-a contemptible person

snarf-eat.

snatch job-kidnapping.

snuff-murder.

sosh-rich kid.

statch-statutory rape.

strung-addicted to heroin.

sub rosa-secret.

swish-gay man.

T

tomato-woman.

toss-search.

trigger-a hired killer.

trotters-horse races.

twist-a woman.

U

V

W

wet arts-politically motivated murder.

X

Y

YA-Youth Authority.

Z

zorched-Intoxicated.

Roger Moore 1927 -2017

I found out that Sir Roger Moore had passed away while I was at work. A colleague said to me: ‘They won’t need to canonise him, he was already a Saint.’ I had a lump in my throat, but I felt it was just the sort of one-liner Sir Roger would appreciate.

To me, as a kid, there was just no other James Bond but Roger Moore. He had humour in his voice and kindness in his manner. He made everything seem effortless and brought joie de vivre to the series. Critics might argue that is the polar opposite of what a spy should be. Everyone has their own opinion about Bond and, for me, the Bond films are neither fantasy nor gritty espionage thrillers but romantic adventures. Moore made the role his own in this regard.

He was underrated as an actor and that partly stems from a lifetime of self-deprecation. If you don’t take yourself seriously, the critics won’t either. But if you look past the constant dismissals of his own talent, you could find a very skilled, engaging actor. He was a gentleman, but also a man’s man, equally at ease onscreen in the hotel lobbies of Monaco as he was in the gold mines of South Africa. It was his roles in films such as The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970), Shout at the Devil (1976), The Wild Geese (1978) and The Sea Wolves (1980) that played a part in keeping the British film industry afloat during the 1970s, or as he might have put it, ‘keeping the British end up Sir’.

I felt privileged to have seen him on stage a couple of years ago. Thank you for that Sir Roger, and for a childhood brought up on the greatest film series in history.

The Man Who Introduced Me To James Ellroy

For the following piece we welcome back to the blog James Ellroy aficionado and all-round good guy Jason Carter. Here’s Jason’s bio:

Jason Carter is an unofficial Ellroy scholar with 20-years of Ellrovian tutelage under his belt. A devoted follower of Ellroy since the age of 14, Jason now has the enviable honor of calling Mr. Ellroy his friend. Although, don’t think of asking Jason for any personal details about Ellroy, as Jason is ferociously protective of Mr. Ellroy’s privacy. Jason, like Ellroy, lives in Denver, Colorado.

I love a good mystery. It’s even more entertaining when the person telling it has such an unforgettable voice.

For the 14th installment of James Ellroy’s award-winning Denver film series In A Lonely Place, the Demon Dog selected House of Bamboo, a 1955 noir directed by Samuel Fuller and shot on-location in Japan. The film stars Ellroy’s occasional Bel-Air Country Club caddy client, Robert Stack, who would later go on to host the television show Unsolved Mysteries, from 1987-2002.

“This movie stars the very man who introduced me to you… Robert Stack,” I remarked to Ellroy shortly before the film began. “Did you know him?” Ellroy asked me. “No,” I replied, “but I did watch Unsolved Mysteries almost every week when I was younger, and that’s how I encountered you for the very first time… No one expects an episode of television to change their life; but that episode was quite the exception.”

The episode I was referring to, which detailed Ellroy’s efforts to reinvestigate the 1958 murder of his mother, occurred during the eighth season of Unsolved Mysteries, originally airing on March 22, 1996. I was 14 years old when I first saw it. As any seasoned Ellroy scholar knows, Ellroy thoroughly documented this fruitless, yet massively insightful quest in his 1996 autobiography My Dark Places, by far one of the most unsparingly honest autobiographies you will ever read, even if you’re not an Ellroy fan. (You can watch the episode, fatuously re-shot with Dennis Farina standing in for Stack here) or read the transcript of the episode here .

The episode I was referring to, which detailed Ellroy’s efforts to reinvestigate the 1958 murder of his mother, occurred during the eighth season of Unsolved Mysteries, originally airing on March 22, 1996. I was 14 years old when I first saw it. As any seasoned Ellroy scholar knows, Ellroy thoroughly documented this fruitless, yet massively insightful quest in his 1996 autobiography My Dark Places, by far one of the most unsparingly honest autobiographies you will ever read, even if you’re not an Ellroy fan. (You can watch the episode, fatuously re-shot with Dennis Farina standing in for Stack here) or read the transcript of the episode here .

Towards the end of the book, Ellroy details the filming of this Unsolved Mysteries episode, even describing how the casting director commended the Demon Dog’s act when re-creating the haunting and heart-breaking scene where Ellroy views his mother’s homicide file for the first time:

“They filmed our segment in four days. They shot Bill and me at the El Monte station. I re-enacted the moment at the evidence vault. I opened a plastic bag and pulled out a silk stocking.

It wasn’t the stocking. Somebody twisted up an old stocking and knotted it. I didn’t pick up a simulated sash cord. We omitted the two-ligature detail.

The director praised my performance. We shot the scene fast.”

There was definitely a magnetic presence there when I watched the Ellroy episode for the first time. I’ve described it as a spiritual vibration, or a current of energy, an irresistible intrigue drawing me to a place many years into the future. I had never heard of Ellroy before seeing that episode. I never expected something as banal as television to introduce me to my favorite writer. And never in a billion years would I ever anticipate my favorite writer to serendipitously come into my life some twenty years later!

The Unsolved Mysteries episode garnered a dizzying whirlwind of tips from viewers, all of them unsubstantiated, and all documented in My Dark Places. One astounding feature of Ellroy’s autobiography is that it catalogues—with laser-like precision—the mind-numbing frustration and countless dead ends that distinguish a real homicide investigation. This is an extraordinary risk that no novelist would ever even dare attempt.

Cosmic Crosscurrents

In 2002, I read Hollywood Nocturnes, Ellroy’s 1994 anthology of short stories. A short nonfiction piece entitled “Out of the Past” begins that book, and concerns his lifelong fascination with famed accordionist Dick Contino. Just as I was introduced to Ellroy via television, the 10-year-old Ellroy was introduced to Contino in the same way. A year or so after seeing Contino on TV, Ellroy caught Contino’s 1958 hotrod film Daddy-O. A year or so after discovering Ellroy on Unsolved Mysteries, I saw the Curtis Hanson, Brian Helgeland-helmed adaptation of L.A. Confidential. That film sent me on an Ellroy-reading torrent over the next many years. I read through Ellroy’s catalogue, along with hundreds of Ellroy interviews.

“I should have seen Dick Contino coming a long time ago. I didn’t. Fate intervened” Ellroy writes in “Out of the Past”. I should’ve seen James Ellroy coming a long time ago. I should’ve snapped to the meaning of that spiritual vibration, and read the future in the coherence of the past.

I didn’t.

Fate intervened.

Ellroy moved to Denver, Colorado, my high-altitude hometown in August, 2015. I’d met Ellroy once before on the Denver stop of his Blood’s A Rover tour in 2009, but our lives truly collided thanks to Ellroy’s monthly Denver film series, begun in September, 2015.

“Out of the Past” reveals that it took Ellroy three viewings of Contino’s Daddy-O to fully comprehend its plot. It took me many re-readings to fully grasp the gravity of Ellroy’s novels.

“Tell me what this man’s life means, and how it connects to my life,” Ellroy wrote of Contino. I could say the exact same thing about James Ellroy. This passage has always haunted me. Now I know why.

On Monday, April 24, 2017, I was with Ellroy, sitting next to him, no less, when he and I both learned—simultaneously—that Dick Contino had passed away at age 87.

In House of Bamboo, Robert Stack stars as US Army Investigator Eddie Kenner, who is on special assignment to investigate a murderous clique led by ex-soldier Sandy Dawson (Robert Ryan). Kenner curries favor with Dawson and his inner circle, gaining their trust while beginning a relationship with Mariko (Shirley Yamaguchi), the wife of a murdered gang member. When the police are tipped off about a planned robbery, the portentous Dawson suspects there’s a traitor among them.

In House of Bamboo, Robert Stack stars as US Army Investigator Eddie Kenner, who is on special assignment to investigate a murderous clique led by ex-soldier Sandy Dawson (Robert Ryan). Kenner curries favor with Dawson and his inner circle, gaining their trust while beginning a relationship with Mariko (Shirley Yamaguchi), the wife of a murdered gang member. When the police are tipped off about a planned robbery, the portentous Dawson suspects there’s a traitor among them.

“What was it like to caddy for Robert Stack?” I asked Ellroy after the film. “He wanted to talk about guns,” Ellroy said. “Just guns.”

Robert Stack certainly knew plenty about guns. A world-class skeet shooter, (Skeet Shooting is one variation of competitive clay pigeon shooting) at 16 years old, Stack became a member of the All American Skeet Team, eventually going on to set two skeet shooting world records, and, in 1971, was inducted into the National Skeet Shooting Hall of Fame. According to publishing magnate Robert E. Petersen, Stack’s friend and longtime shooting partner, “Shooting was [Robert’s] first and true passion in life.”

Stack most famously portrayed the iconic crime fighting prohibition agent Eliot Ness in the award-winning ABC television hit drama series, The Untouchables from 1959–1963. The show portrayed the ongoing battle between gangsters and a special squad of federal agents in prohibition-era Chicago, and won Stack a Best Actor Emmy Award in 1960. He would later star in three other drama series, sharing the lead with Tony Franciosa and Gene Barry in The Name of the Game (1968–1971), Most Wanted (1976), and Strike Force (1981).

In The Name of the Game, Stack played a former federal agent turned true-crime journalist, evoking memories of his role as Ness. Similarly, in both Most Wanted and Strike Force, he played a tough, incorruptible police captain commanding an elite squad of special investigators, once again conjuring memories of Ness. Stack would eventually reprise the Ness role in the 1991 television movie The Return of Eliot Ness.

In 1987, Stack began hosting Unsolved Mysteries. He thought highly of the interactive nature of the show, remarking that it created a “symbiotic” relationship between viewer and program, and that the hotline was a great crime-solving tool. Unsolved Mysteries aired from 1987 to 2002, first as specials in 1987 (Stack did not host all the specials, which were previously hosted by Raymond Burr and Karl Malden), then as a regular series on NBC (1988–97), CBS (1997–99) and finally on Lifetime (2001–02). Stack served as the show’s host during its entire original series run.

When Ellroy reunited with Stack in 1996 for the filming of the Jean Ellroy segment, Ellroy, fresh from the publication of American Tabloid, reminded Stack of how they had met years earlier on the golf course.

“Did I talk about guns?” Stack asked with a bit of a chuckle.

Ellroy was astonished, “Yes you did!”

The Demon Dog’s final encounter with Stack occurred at the University of Southern California’s 1997 Scripter Awards, an annual ceremony honoring the year’s best film adaptation of a book. The honored film that year was—accordingly— L.A. Confidential. Ellroy, Curtis Hanson and Brian Helgeland were all formally recognized that evening. Stack and Ellroy shared a brief conversation, with the Demon Dog once again reminding Stack of how he caddied for the Unsolved Mysteries host many years earlier.

Robert Stack died at 84 in May, 2003. I was a boozed-out, sugar-shoveling 22-year-old (I hadn’t yet heeded the Demon Dog’s sobriety call) and working at a small daily newspaper in shitsplat south eastern Colorado when I caught the news.

Later, in November of that year, Stack’s extensive gun collection was auctioned off in Anaheim, California at the request of his estate. Items on the auction block included his Parker BHE Skeet Grade 28 gauge SXS shotgun with a brass inlay inscribed “National Skeet Championship 1936, 20 ga. Runner-Up, Bob Stack, Score 97×100”; a Ruger 20 gauge over/under shotgun presented to Stack by company founder William B. Ruger and the factory inscription “To Robert Stack from William B. Ruger, 1978”; and Stack’s shooting jacket with various team, tournament and police patches.

Though I’m quick to dismiss television today, finding it a fatuously hyper-kinetic massive corporate distraction, I can’t think of the haunting statement “Perhaps YOU may be able to help solve a mystery…” without hearing Robert Stack’s confident and incomparable brogue. I owe him a staggeringly incalculable debt of gratitude. He gave me my greatest teacher in this life, James Ellroy, and an attendant lifelong intellectual Ellrovian expedition that grows stronger with every day.

Thank you, Mr. Stack.

Three Chords and the Truth – Review

Hector Lassiter is one of the most compelling literary creations of recent years– a crime novelist who ‘writes what he lives and lives what he writes’. Lassiter was born January 1, 1900, and he witnesses some of the most tumultuous events of the twentieth century. Whether he finds himself at the heart of a murder mystery with the Lost Generation in 1920s Paris, or dodging the bombs and bullets with Ernest Hemingway during the Spanish Civil War, Lassiter is never far away from violence and intrigue. Three Chords and the Truth is the tenth and final novel in the Lassiter series, and, needless to say, it was eagerly anticipated by the many fans of the series.

Hector Lassiter is one of the most compelling literary creations of recent years– a crime novelist who ‘writes what he lives and lives what he writes’. Lassiter was born January 1, 1900, and he witnesses some of the most tumultuous events of the twentieth century. Whether he finds himself at the heart of a murder mystery with the Lost Generation in 1920s Paris, or dodging the bombs and bullets with Ernest Hemingway during the Spanish Civil War, Lassiter is never far away from violence and intrigue. Three Chords and the Truth is the tenth and final novel in the Lassiter series, and, needless to say, it was eagerly anticipated by the many fans of the series.

Craig McDonald is the author behind the author, the creator of Hector Lassiter and the writer of five more novels outside the Lassiter series. McDonald began his career as a journalist and still works in that field today. Before his own fiction was published McDonald interviewed such crime writing luminaries as Ken Bruen, Karin Slaughter, Ian Rankin and the Three James’s (Crumley, Ellroy and Sallis). One wonders if McDonald’s conversations with these titans of the genre, creators of their own authorial personas, had a role in how he conceived Lassiter, an author immensely conscious of his own image. I had the pleasure of interviewing Craig last year (you can read our long discussion here) and we talked about the genesis and inspiration behind the Lassiter character and novels.

The novel begins with a depiction of the real-life 1958 incident when the US air force jettisoned a nuclear bomb off the coast of Tybee Island South Carolina after a collision between a B-47 Bomber and F-86 Fighter Plane. The (thankfully) unexploded bomb was never recovered giving free range for McDonald to concoct a wild fictional aftermath. Lassiter, as is so often the case, finds himself to be the right man in the wrong place: Nashville, 1958, Hector is stranded in a snowstorm and gets caught in a caper involving Federal agents, unhinged Country & Western stars and a right-wing racist cabal (who are the last people on earth anyone would want a nuclear weapon to fall into the hands of). There are shades here of the apocalyptic-themed film adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s Kiss Me, Deadly (1955), but it’s not just the threat of a nuclear catastrophe that looms large over the novel, there is also a complete meta-fictional reworking of the Lassiter character and authorial persona which will make you question the nature of every page of the entire series. Take this description of crime writing in the novel:

The craft of fiction writing had earned the fifty-something Lassiter a good and steady living; nice threads, pretty women and a chance to roam widely: to see a bigger world than he would ever have glimpsed working some nine-to-five, wage-slave day job in his native Southern Texas.

It is the ‘bigger world’ that every reader and writer in their heart aspires to, and the one that McDonald has given us through the Lassiter series, which is given a radical new perspective in the final pages of Three Chords.

The best Lassiter novels are the ones that give you a vivid sense of era and setting. Fans of Country music and the Nashville scene and nuclear war paranoia will rank Three Chords as their favourite Lassiter tale, but for me, I marginally prefer Death in the Face as the novel is a tribute to Ian Fleming and the world of James Bond which resonated with my cultural interests more strongly. Still, Three Chords is a superb novel and powerful coda to the Lassiter series.

In the Library

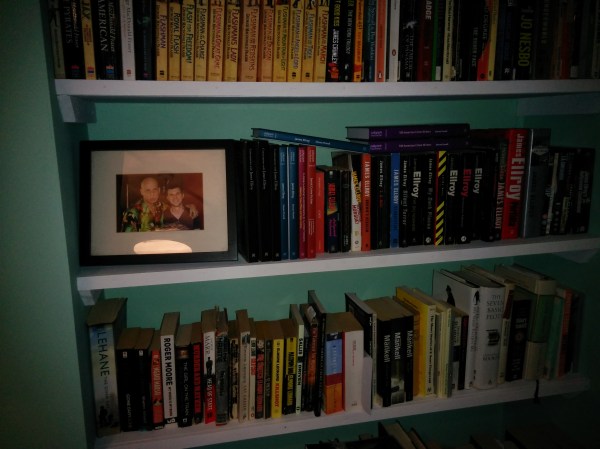

Apologies for the lack of posts recently. I’ve been busy with other projects, including a new book project editing an anthology of critical essays on James Ellroy. I’m very excited about that, and at the thought of getting back to blogging soon.

I’ve also had time to have my study redecorated. I’m very pleased with it, and for the first time I really feel like I have my own private library. There is a dedicated Ellroy shelf with a photo of the Demon Dog and I taken back in 2009. It’s overlooking the computer so he can keep an eye on me and make sure I’m working.

James Ellroy’s Denver Film Series: In a Lonely Place

For the following piece we welcome back to the blog James Ellroy aficionado and all-round good guy Jason Carter. Here’s Jason’s bio:

Jason Carter is an unofficial Ellroy scholar with 20-years of Ellrovian tutelage under his belt. A devoted follower of Ellroy since the age of 14, Jason now has the enviable honor of calling Mr. Ellroy his friend. Although, don’t think of asking Jason for any personal details about Ellroy, as Jason is ferociously protective of Mr. Ellroy’s privacy. Jason, like Ellroy, lives in Denver, Colorado.

“Woof, woof—hear the Demon Dog bark—he’s got a twelve-inch wanger that glows in the dark. I’m the king of writers, woof woof, woo woo, I got a 12-year-old girlfriend strung out on glue. I’ll end this poem and beat my meat, because, cats, tonight, you’re in for a treat…”

Thus began James Ellroy’s introductory comments on the 11th installment of his award-winning monthly Denver film series. This month’s offering was In a Lonely Place, a 1950 film noir directed by Nicolas Ray, and starring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame. The Denver film series is named ‘In a Lonely Place’ after this classic noir, so to hear Ellroy finally give his take on the movie was very special. Over the past year, Ellroy’s series has delivered cinematic masterpieces as diverse as Akira Kurosowa’s High & Low, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Robert Altmann’s Nashville, the Coen brothers’ Miller’s Crossing and Bo Widerberg’s The Man On the Roof, all preceded by Ellroy’s incomparable commentary.

I once said on this blog that the films Ellroy selects reflect the passionate crimes of the heart which dominate his novels. This is certainly true, but I’ll include that such a sundry lot also dynamically demonstrates the breadth and depth of James Ellroy’s interests and imagination. Ellroy is right when he says he is no longer a crime writer, but a historical novelist… Ellroy certainly knows the story of man, and is never afraid to tell it from the most savagely honest perspective imaginable. If only Ellroy’s detractors could see him like this, they would witness an intellectual passion that runs far deeper than any of Ellroy’s infamously profane Demon Dog performances. (I’m looking at you, Mike Davis!)

“In a Lonely Place the movie is not as good as its source material,” Ellroy continued, referencing Dorothy B. Hughes seminal crime novel. Ellroy was less flattering when describing Bogart. “Bogie was a pissed off little guy nobody would ever mistake for a good guy,” Ellroy intoned, adding “Bogie was, at that time, the Daffy Duck of male movie stars… he thinks he’s cool, but really isn’t.”

In A Lonely Place tells the story of Dixon Steele (Bogart), a has-been Hollywood screenwriter with an explosive temper. Steele takes a coat check girl home with him, and the very next day the girl is found murdered. Steele is interrogated as the prime suspect as he was spotted with the victim by his neighbor Laurel Gray (Grahame). Gray is also brought to the police station, confirms the girl left Steele’s home unharmed, and Steele is released. As Steele and Gray slowly begin a relationship, Steele’s writing ability recovers, and he dives into his work. However, Steele begins to act strangely, and even forces an old army buddy and the man’s wife to participate in a bizarre re-creation of the murder based on the known facts of the case. The police captain who interrogated Steele shows Steele’s lengthy record of erratic and violent behavior to Gray, who, accordingly begins to doubt Steele’s innocence. The film ends with an eleventh-hour twist and the tragic specter of a future which cannot be built on the destruction of the past.

“The movie showcases the great L.A. iconography on top of everything else,” Ellroy said in his introduction. Part of that iconography is most certainly the grand isolation and hapless verisimilitude of celebrity, topics which Ellroy has explored in his novels for decades. As Ellroy himself said in My Dark Places, “Isolation breeds self-pity and self-loathing”; both of which are on abundant and yet subtle display in Humphrey Bogart’s Dixon Steele, who at one point even says “There’s no sacrifice too great for a chance at immortality…”

“The movie showcases the great L.A. iconography on top of everything else,” Ellroy said in his introduction. Part of that iconography is most certainly the grand isolation and hapless verisimilitude of celebrity, topics which Ellroy has explored in his novels for decades. As Ellroy himself said in My Dark Places, “Isolation breeds self-pity and self-loathing”; both of which are on abundant and yet subtle display in Humphrey Bogart’s Dixon Steele, who at one point even says “There’s no sacrifice too great for a chance at immortality…”

Ellroy was no less sparing of Gloria Grahame, and director Nick Ray, who were married at the time In A Lonely Place was made. “Nick Ray put evil clauses in the film contract Gloria had to abide by,” Ellroy said, referencing contract stipulations dictating that “my husband [Ray] shall be entitled to direct, control, advise, instruct and even command my actions during the hours from 9 AM to 6 PM, every day except Sunday…I acknowledge that in every conceivable situation his will and judgment shall be considered superior to mine and shall prevail.” Grahame was also forbidden to “nag, cajole, tease or in any other feminine fashion seek to distract or influence him.”

Their marriage would not survive the filming. Afraid that one of them would be replaced, Ray began sleeping in a dressing room, under the pretext that he needed to work on the script. Grahame acquiesced, and nobody on the set knew of the separation. Though they briefly reconciled, they would divorce in 1952, after Ray found Grahame in bed “doing the bad boogaloo” with his thirteen-year-old son, a part of the story Ellroy had particularly savage fun in re-telling.

After the film, we gathered in the theater’s bar to discuss it, which has always been my favorite part of every one of Ellroy’s film screenings. With Ellroy at the helm as a deft master of ceremony, the conversations which develop can often become as wonderfully convoluted as any of the plotlines from his novels. Even when jet-lagged (Ellroy had just returned to the states after a visit with his international publisher in France), the Demon Dog is still an indomitable force. On this particular evening, Ellroy regaled us with sordid tales from his roaring 20’s, including numerous run-ins with the LAPD. Speaking of running—don’t do it. “Never, ever run from the LAPD,” Ellroy warned us. “They’ll catch you, and kick your ass!” Ellroy then told us of a time when he ran after committing a petty theft.

“Ask me anything about politics or Hollywood,” Ellroy said, seamlessly shifting gears. One patron mentioned the Kennedy clan and Lyndon Johnson. “The Kennedys are stale bread,” Ellroy denounced. Ellroy does indeed have an encyclopedic knowledge of politics, Hollyweird, and all forms of sleaze in between. However, I’ve sworn never to repeat online most of what he’s told me.

I mentioned—to Ellroy’s surprise—that Curtis Hanson had shown In a Lonely Place to Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe as part of a mini film series to prepare the then-unknown Aussie actors for their roles in L.A. Confidential. (Ellroy actually began his Denver film series—in September, 2015—with L.A. Confidential.) Continuing in the Hanson vein, I told Ellroy I heard the Demon Dog had a blink-and-you’ve-missed-it cameo in Hanson’s 2000 film Wonder Boys. Ellroy said that yes it was true, adding with typical Ellrovian pizzazz, that the film’s crew put him up in a hotel swarming with bedbugs. We were quite shocked to learn of Curtis Hanson’s untimely death just one day later.

Eventually, the conversation came around to an assassination attempt on legendary L.A. gangster—and Ellroy mainstay—Mickey Cohen in which the Mickster jumped on his pet bull dog to protect him. (Both Mickey C. and the dog survived). I held up my DVD of Reinhard Jud’s 1993 documentary Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction, and asked Ellroy if this is what he meant when Ellroy said in the documentary how Mickey was good-natured, despite his profession. Ellroy grinned at me and chuckled, leaving the question as open to interpretation as the endings of most of his novels.

After 20 years, I should expect nothing less.

I was a fan THEN.

I’m still a fan NOW.

Curtis Hanson (1945-2016)

I was saddened to learn this morning of the death of film director and screenwriter Curtis Hanson. Hanson will forever be remembered for adapting (with Brian Helgeland) and directing the big screen adaptation of James Ellroy’s novel L.A. Confidential. Hanson had already built a reputation as a director with a brilliant grasp of genre with the thrillers The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992) and The River Wild (1994), before he began work on adapting what is perhaps Ellroy’s most complicated novel. Ellroy himself had said of L.A. Confidential:

I knew my book was movie-adaptation-proof. The motherfucker was uncompressible, uncontainable, and unequivocally bereft of sympathetic characters. it was unsavoury, unapologetically dark, untameable, and altogether untranslateable to the screen.

But for Hanson it was a labour of love, he said of Ellroy’s fiction:

Many find Ellroy’s novels unremittingly dark. I don’t. His humor and strength of personality shine through. He’s a survivor. Whether he intends it or not, that strength of spirit illuminates even the darkest of his nightmare visions.

The screenplay took some major deviations from the novel, all for the better in my opinion, making the narrative more linear and comprehensible for the screen. The fate of Jack Vincennes is completely different in the film than it is the novel, but rightly so as I’ll never forget the shock I felt the first time I saw the kitchen scene with Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) and Dudley Smith (James Cromwell), where Spacey fatefully whispers ‘Rollo Tomasi’.

It’s worth noting too that every time I watched an interview with Hanson I was struck by how kind and even-tempered he sounded, completely destroying the myth that the best directors are tyrants who have to mentally torture their actors to get the best performances. I imagine he was a joy to work with.

Curtis Hanson with Guy Pearce and James Ellroy

Hanson and Helgeland won an academy award for their screenplay adaptation of LA. Confidential, but shamefully the bauble for Best Picture that year went to James Cameron’s hammily acted, drearily written and thoroughly waterlogged Titanic. Hanson never quite matched the success of L.A. Confidential with his later films, but lets face it who could? I would highly recommend his comedy-drama Wonder Boys (2000), a charming but incisive portrayal of academe which has a blink and you’ll miss it cameo from Ellroy.

In any event if Curtis Hanson had never made another movie L.A. Confidential would still have been a big enough achievement for a lifetime. He took Ellroy’s unfilmable novel and turned it into a neo-noir masterpiece and one of the best crime films of all time. I’ll be watching it tonight for the umpteenth time in tribute to him, and perhaps I might feel a slight lump in my throat when Lynn Bracken (Kim Basinger) whispers in that irresistibly sexy voice ‘Some men get the world. Others get ex-hookers and a trip to Arizona.’

Thank you Curtis Hanson.

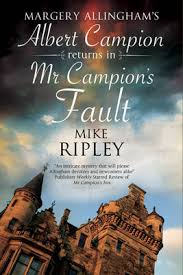

Mr Campion’s Fault – Review

Continuation novels are a tricky business as an author is always likely to run in to an army of purists who will automatically dislike their work as infringing on the body of work of their literary hero. As much as I disapprove of this form of genre small-mindedness it does have a certain logic. I always enjoyed John Gardner’s James Bond novels for instance, although I have to concede they do not remotely touch the work of Ian Fleming.

Continuation novels are a tricky business as an author is always likely to run in to an army of purists who will automatically dislike their work as infringing on the body of work of their literary hero. As much as I disapprove of this form of genre small-mindedness it does have a certain logic. I always enjoyed John Gardner’s James Bond novels for instance, although I have to concede they do not remotely touch the work of Ian Fleming.

Mike Ripley’s decision to continue the Albert Campion series more than forty years after Margery Allingham’s death was at the very least a brave one. After all, Allingham was one of the most revered authors of the Golden Age and her aristocratic detective appeared in eighteen of her novels and countless short stories. The series was first revived by Allingham’s widower Philip Youngman Carter and Ripley’s first entry in the series, Mr Campion’s Farewell (2014), was the completion of a Youngman Carter manuscript. This was followed by Mr Campion’s Fox (2015) and now we have Mr Campion’s Fault.

In Mr Campion’s Fault the sudden death of the senior English master, Bertram Brown, of Ash Grange School for Boys brings Mr Campion to the fictional Yorkshire village of Denby Ash where his son Philip is coaching the school rugby team and his daughter-in-law Perdita has been trying to keep the late Brown’s long-planned musical production of Dr Faustus alive. Campion walks into an environment where miners are considered the upper classes, Methodism vies with local folklore about poltergeists as the dominant superstition, and northern bluntness is almost a foreign language to the well-heeled sleuth who begins to suspect that Brown’s death in a car accident may not have been so accidental after all. It’s not just Campion who found the setting alien. Any youngish British reader might believe they are reading about another world at times, but that, for me, was part of the appeal. I was enticed by descriptions of coal-mining in all its beauty and horror:

Mr Campion had gently steered the conversation to include the history and sociology of Denby Ash.

It had been, the headmaster had informed him, a pet theory of the late Bertram Browne that the people of Denby Ash were inextricably linked, economically and philosophically, to the seams of coal which ran under the village. With his background as a Sapper, the late Mr Browne had naturally taken an interest in matters geological and the ‘black gold’ on which the prosperity of the local population depended and whose bounty had been, in a way, responsible for the existence of Ash Grange School. There were those who found it whimsical that the long, subterranean solid rivers of coal were known as ‘Flockton Thick’ and ‘Flockton Thin’. Indeed, certain habitués of the Staff Room, who really should have known better, used the expression to describe formal gatherings of the Mothers’ Union, but not Bertram. He knew that Flockton Thick referred to twin seams each two-feet thick, whilst Flockton Thin was a 15-inch layer of coal of the very highest quality, and neither were laughing matters for down there, six hundred feet underground, the men of Denby Ash (and, a century ago, not a few women and children) had lost their lives harvesting them.

Ripley admits that ‘Yorkshire was certainly not a natural hunting ground for Margery Allingham and taking the Campions there may be a risk’ but he imbues the new setting with both attention to detail and a witty affection culled from his own childhood upbringing in the West Riding. Sprinkled with the biting wit readers of Ripley’s Angel novels and his Getting Away With Murder column have become accustomed to, Mr Campion’s Fault is a welcome addition to the series which has the potential to draw in new readers and win round Allingham purists.

Albert Teitelbaum – The Man Who Sued James Ellroy

James Ellroy is often asked whether his fictional portrayals of real-life historical figures have ever lead to legal problems. In 1996 he told interviewer Paul Duncan, ‘I have never gotten into trouble using real people in my books because they are dead and can’t sue me. […] The Kennedy’s, for instance, would never sue. So much is written about them that, if they were to sue, they’d be in court all day, every day, and that way they wouldn’t have time to [text deleted].’

However, within a few years of this statement, Ellroy had inadvertantly broken his own cardinal rule and was being sued to the tune of $20,000,000. The plaintiff was not a member of the Kennedy clan, but a retired and long- forgotten Hollywood furrier named Albert Teitelbaum.

‘Tijuana, Mon Amour’ is a typical piece of work from Ellroy’s short story/novella period. Hush-Hush editor Danny Getchell alliteratively narrates a sordid tale of 1950s Hollywood shenanigans loosely revolving around a payola scandal, a fake fur heist and a child Labour camp in Tijuana (a locale which has become the Sodom and Gomorrah of the noir world). Heavily reliant on pastiche and Ellroy’s willingness to offend, it ranks among my least favourite of the Demon Dog’s works. It is rather apt then that the most notable thing about the story is it led to Ellroy being sued.

In the story Getchell and cohort Sammy Davis Jr become embroiled in a fake fur heist and insurance scam arranged by Teitelbaum. Ellroy had rashly presumed Teitelbaum was dead and based the fur heist on a real-life ‘robbery’ which happened at Teitelbaum’s fur store on December 27, 1955. Teitelbaum reported to the police that four men bound him and an assistant at gunpoint and then stole furs worth $280,000, but a county grand jury later indicted him for faking the heist. Teitelbaum was found guilty and sentenced to one year in the Los Angeles County Jail (years later, Ellroy would do time in the same institution). Teitelbaum could hardly complain that Ellroy fictionalised the fur heist. After all he was found guilty and the conviction was upheld despite several appeals. However, the basis of Teitelbaum’s claim was that Ellroy has the fictional Teitelbaum caught ‘buck-naked’ in the boudoir with Linda Lansing and real-life murderess Barbara Graham. In addition, Ellroy elaborated on the heist to have Teitelbaum using Lansing to fence the furs for him in Tijuana, a detail Teitelbaum’s lawyer Charles Morgan, who hounded The New Yorker for ten years in an infamous libel case, was adamant never occurred. Subsequently, when ‘Tijuana, Mon Amour’ was reprinted in the anthology Crime Wave (1999) the Teitelbaum character was renamed Louie Sobel, amusingly after Ellroy’s literary agent Nat Sobel who rescued his career in the 1980s (although they have recently parted ways). Here’s how the heist is described in the story (in recognition of the Teitelbaum lawsuit, the furrier below is named Louie Sobel):

I went in as the Wolfman. Sammy crept in as the Creature from the Black Lagoon. We moved our minkmobile into the back lot and barged in the back door.

5:46 P.M.

Fourteen minutes to filch furs and fill up the van. Fourteen minutes to fuck the fur-filchers already assigned to the job.

We monster-minced down a mink-lined hallway. We froze by the freezer vault. Louie Sobel latched eyes on on us and laughed long and loud.

He howled and heaved for breath. He broke a sweat and swatted his legs. He swayed and pointed to a pile of pelts on the freeer floor.

He hocked into a hanky. He said, “Go, you fershtunkener furmeisters. Go, before I die of a fucking coronary.”

Sammy popped the pelts into a large laundry bag. I shot my eyes into the showroom. I scanned scads of sensational sables and choice chincillas and magnificent minks. Our paltry pile of pelts paled in considered contrast.

Sobel said, “Hit me once, tie me up, and get out of here. Your theatrics are wearing me thin.”

I pulled my piece and pistol-whipped him to a pulp. I decimated his dentures. Blood dripped on my dress blues.

Sobel sunk into dreamland. I dropped him in the freezer and gagged him with a gorgeous gaggle of furs. Sammy gloated and glared at the ofay oppressor. He muttered mau-mau musings and metamorphosed into the Creature from the Coon Lagoon.

Although Ellroy has said little about the Teitelbaum controversy since, probably as a consequence of the settlement which I imagine was a lot less than the 20 million asking price, it can not be overstated the negative affect it had on his career. At the height of the lawsuit, GQ Editor-in-Chief Art Cooper (who had personally hired Ellroy) threw a party in Ellroy’s honour (Ellroy has been awarded GQ Novelist of the Year award twice). Carl Swanson reported from the event: ‘Mr Ellroy did not look to be in much of a partying mood. In fact, guests noted that he did not work the room much, and they spotted him talking solemnly with Mr Cooper by the stairway at the end of the bar.’ It’s also probably not a coincidence that within a few years both Cooper and Ellroy would be fired by GQ. Ellroy would lament in an interview with Craig McDonald a few years later, ‘Astonishingly, I got the boot. Odd.’

So who then was Albert Teitelbaum, the man who somewhat inadvertantly caused Ellroy so much grief at the height of his literary career? The more I read about him, the more I feel a soft spot for the self-styled ‘furrier to the stars’. For instance, he designed a ermine eye patch for Elizabeth Taylor, but she couldn’t wear it ‘because of the dangers of fur next to my eye. But I loved the idea’ Taylor is reported to have said by biographer William J. Mann. In addition to his splendidly Ruritanian career as a furrier, Teitelbaum also spent time as the manager of Mario Lanza. As Lanza’s biographer Derek Mannering put it:

Why or how anyone thought that a Beverley Hills furrier would be an appropriate person to handle the career of the most famous – and to some the most infamous – tenor in the world is not clear. But to Teitelbaum’s credit he lost no time in getting to work.

Lanza and Teitelbaum and their wives had been friends for years and the tenor took a chance on Teitelbaum when his career was floundering. Unfortunately for Lanza, Teitelbaum’s fortunes had also turned and Lanza’s reputation would be tainted in an impending scandal. Lanza was among a host of Hollywood celebrities who acted as character witnesses for Teitelbaum at his trial, others included Joan Crawford and Louella Parsons. Lanza was integral to Teitelbaum’s defence as he arrived at the store shortly after the staged robbery and testified he found Teitelbaum ‘upset and shaking’. Unfortunately for Teitelbaum, Lanza’s arrival at the store may have been his undoing as legal documents show it was unlikely 280 furs could have been removed between the time of the alleged robbery and his meeting with Lanza:

The crux of the entire case was whether the furs for which appellant made claim against his insurance carrier were stolen on the night in question, i.e., did a robbery take place on that night or was there merely a fake robbery. Appellant offered no direct evidence to controvert the testimony of Weiss as corroborated by the confession of the appellant that the alleged robbery was faked and that no furs were stolen. The only witness called by the defense as to the event was the witness Stan. His testimony practically dovetailed with that of Weiss. While the evidence produced by the appellant showed that it was possible for four men to remove 280 fur garments from the vault to a vehicle in the alley within the short period of time that elapsed before the witnesses Lanza [163 Cal. App. 2d 224] and Walge arrived at appellant’s place of business, there was not an iota of evidence that more than one alleged robber was in the store.

According to Lanza’s biographer Roland L. Bassette the tenor ‘was dragged into the sordid mess by circumstance and association. His fortunes were not advanced by the publicity that resulted.’ However, Lanza and Teitelbaum would not part ways immediately. Teitelbaum was with the singer in Italy when Lanza was starring in the movie Seven Hills in Rome (1958) when he learned his conviction was upheld on appeal. He resigned as Lanza’s manager and returned to the U.S. to serve his sentence. According to Jeff Rense, whatever Teitelbaum’s faults he had a massively beneficial effect on Lanza’s life, and especially his movie career: ‘I can also state that without Al Teitelbaum, we would NOT have either Serenade or The Seven Hills Of Rome (and probably For The First Time) to view and treasure today. […] The story of how Al was flown to Italy by MGM on a moment’s notice to save and oversee the floundering production of Seven Hills is, well, amazing. Al literally guided the day by day production of the entire film.’ Nicky Pelligrino’s novel When in Rome (2012) gives a fictional portrayal of Lanza’s time in Italy with Teitelbaum helping the singer overcome his alcoholism and making his appearance in the film possible.

Teitelbaum died in May 2011 aged 95 or 96, and a full twelve years after Ellroy first presumed he was dead when writing ‘Tijuana, Mon Amour’. Although he cost Ellroy both money and credibility, in many ways Teitelbaum was the ultimate Ellrovian character and I doff my fur hat to him.