Crime Fiction and Censorship

Christa Faust is one of the hottest crime writers around today. A former fetish model and professional dominatrix, Faust’s acclaimed novels such as Chokehold and Money Shot feature indefatigable former porn star Angel Dare. Why do I mention this? Well, partly to recommend Faust’s novels but also to alert you to legislation which in a few years may make it illegal to buy her work and other works of crime fiction in the UK. Tomorrow the European Parliament will vote on a resolution to ban all forms of pornography in the 27 European Union member states. Iceland, which is not in the EU, is considering similar proposals. I don’t consider Faust’s work porn– that’s not the point I’m trying to make. Pornography in its more extreme forms is already outlawed, but as Tom Chivers says at the Telegraph, to ban porn we must necessarily define it and that’s where you can see the EU casting its net into huge swathes of our culture. Chivers gives this example:

Christa Faust is one of the hottest crime writers around today. A former fetish model and professional dominatrix, Faust’s acclaimed novels such as Chokehold and Money Shot feature indefatigable former porn star Angel Dare. Why do I mention this? Well, partly to recommend Faust’s novels but also to alert you to legislation which in a few years may make it illegal to buy her work and other works of crime fiction in the UK. Tomorrow the European Parliament will vote on a resolution to ban all forms of pornography in the 27 European Union member states. Iceland, which is not in the EU, is considering similar proposals. I don’t consider Faust’s work porn– that’s not the point I’m trying to make. Pornography in its more extreme forms is already outlawed, but as Tom Chivers says at the Telegraph, to ban porn we must necessarily define it and that’s where you can see the EU casting its net into huge swathes of our culture. Chivers gives this example:

An old friend of mine who did art at university did a whole exhibition of, basically, photos of body parts and rubber models of other body parts and, really, just lots of body parts. Is that art? Is it pornography? Whether you like it or not we’ve got a decision to make, and if the EU is banning porn, then presumably it’ll be the EU that decides what’s too porny for the Tate Modern.

The nature of bans is they get extended with follow up legislation, and it’s easy to imagine some puritanical bureaucrat taking exception to Faust, or to say Raunchy paperback cover art like this example, or this one, or this one, or this one. It may be porn to them, but its art to us (or at least part of the genre we love). The European Parliament also wants to ‘eliminate gender stereotypes in the EU’ so we can kiss goodbye to the femme fatale and the sexist PI as well. In the US, this costly, impractical (especially in the Internet age) and illiberal legislation wouldn’t be seriously considered due to the First Amendment.

Would we really want to silence our authors in this way?

To illustrate, here’s a funny (NSFW) scene from James Ellroy’s Destination Morgue where Detective ‘Rhino’ Rick Jensen and actress Donna Donohue (based on Dana Delaney) go into a porno bookstore (where incidentally Ellroy himself once worked) looking for evidence on a murder case:

Donna Donahue – right by the bookstore – a bliss blast in LAPD blue.

I double-parked and jumped out. Donna said, “I didn’t have time to change, but it bought us some time here.”

“Say what?”

“I impersonated a cop. The bookstore guy’s cueing up his surveillance film from two days before the robbery. We can stand in a stall in back and watch.”

I walked in first. The clerk ignored me. The clerk salaciously salaamed to Donna. He pointed us down “Dildo Drive” – a mobile-mounted, salami-slung corridor. Packaged porno reposed on racks and shimmied off shelves. It was a donkey-dick demimonde and Beaver Boulevard.

We ducked dildos. We made the booth. Donna doused the lights. I tapped a projector switch. Black-and-white film rolled.

We saw pan shots. We saw ID numbers. We saw Sad-Sack Sidneys slap sandals in slime.

Donna said, “I already checked the credit-card receipts. Nothing from Randall J. Kirst.”

I nodded. “Nobody – not even turd burglars – want credit-card receipts from the fucking Porno Vista.”

Donna said, “Right. We’re looking for two men making purchases together – the victim and the killer I saw.”

Police smarts in forty-eight hours – add breeding and brains. I said, “What kind of work does your family do?”

Donna laffed. “They manufacture toilet seats.”

I yukked. My gut distended. I hyper-humped it back in.

Film rolled. We saw dykes buy dildos. We saw college kids buy Beaverrama, Beaveroo, Beaver Den, Beaver Bash, Beaverooski, and Beaver Bitches. We saw flits flip through The Greek Way, Greg Goes Greek, Greek Freaks, More Is More, The Hard and the Hung, and The Hungest Among Us. I laffed. Donna laffed. We bumped hips for kicks. Donna’s gunbelt clattered.

Moby Dick’s Greek Deelite, Moby Dick’s Athens Adventure, Moby Dick Meets Vaseline Vic. We yukked. We howled.

Parsifal Found!

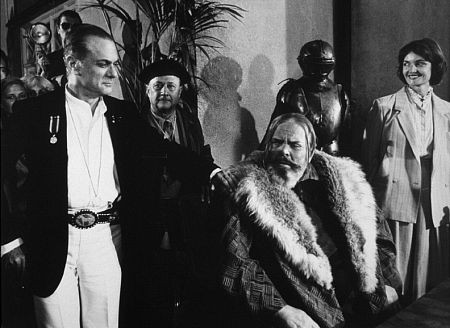

Last June I wrote a post about the obscure film Where is Parsifal? ,which the BFI had listed as one of their 75 missing films. Directed by Henri Holman, the film was screened at the 1984 Cannes film festival and featured a stellar cast including Orson Welles, Peter Lawford, Tony Curtis, Donald Pleasance and Vladek Sheybal, but it was savaged by the few critics that saw it, probably due to its bizarre plot (something to do with the titular character (Curtis) inventing a laser skywriter and trying to sell the patent). My interest in the film stemmed from the involvement of Terence Young as executive producer. Young had been a promising film director at the start of his career and played a significant role in the success of the James Bond film franchise. Young was a friend of Bond creator Ian Fleming and directed three of the first four films in the series. He also groomed Sean Connery for the role as Bond. Sadly, the latter half of Young’s career is tainted by his involvement with bizarre and disastrous projects, such as Inchon (a Korean War movie financed by Unification Church founder Sun Myong Moon which is regarded as one of the worst films ever made) and allegedly The Long Days (1980), a propaganda film about Saddam Hussein which Young is said to have directed and edited for the Iraqi dictator. Young’s involvement with Where is Parsifal? may have also been dubious. In an article for Psychotronic magazine, which examined the life and career of Vladek Sheybal, David Del Valle alleged that Welles only agreed to appear in the film as the producers had (falsely) promised to back his planned film adaptation of King Lear. Whether Young was party to this deception is not known.

Last June I wrote a post about the obscure film Where is Parsifal? ,which the BFI had listed as one of their 75 missing films. Directed by Henri Holman, the film was screened at the 1984 Cannes film festival and featured a stellar cast including Orson Welles, Peter Lawford, Tony Curtis, Donald Pleasance and Vladek Sheybal, but it was savaged by the few critics that saw it, probably due to its bizarre plot (something to do with the titular character (Curtis) inventing a laser skywriter and trying to sell the patent). My interest in the film stemmed from the involvement of Terence Young as executive producer. Young had been a promising film director at the start of his career and played a significant role in the success of the James Bond film franchise. Young was a friend of Bond creator Ian Fleming and directed three of the first four films in the series. He also groomed Sean Connery for the role as Bond. Sadly, the latter half of Young’s career is tainted by his involvement with bizarre and disastrous projects, such as Inchon (a Korean War movie financed by Unification Church founder Sun Myong Moon which is regarded as one of the worst films ever made) and allegedly The Long Days (1980), a propaganda film about Saddam Hussein which Young is said to have directed and edited for the Iraqi dictator. Young’s involvement with Where is Parsifal? may have also been dubious. In an article for Psychotronic magazine, which examined the life and career of Vladek Sheybal, David Del Valle alleged that Welles only agreed to appear in the film as the producers had (falsely) promised to back his planned film adaptation of King Lear. Whether Young was party to this deception is not known.

Anyway, I received a number of positive responses to the original post which made me wonder just how ‘lost’ the film was. One reader alerted me to this French news film available on YouTube which shows a clip from the film and Young and Curtis together at Cannes promoting it. My post was linked on the Italian Wikipedia page about the film which stated it was released on DVD in Italy in 2010 under the title There is Something Strange in the Family. Strange indeed! An Australian reader contacted me to say he had a VHS copy of the film. It was released on VHS in Australia in the 1980s apparently. Sure enough, I found this essay on the BFI website from November last year stating that they have removed Where is Parsifal? from their missing film list after Henri Holman donated his personal 35mm print. It’s wonderful news that they’ve finally tracked down a copy of this strange and elusive film for their archive, but as I discovered, there were quite a lot of copies in circulation for a missing film. It’s going to be a lot more difficult for the BFI to discover other older missing films such as The Mountain Eagle (1926): Alfred Hitchcok’s second film and the only film by Hitch regarded as lost. Still, anything’s possible. Thanks to all the readers who contacted me about the original post.

Looking Back on Theakston’s: The Strange Case of Stephen Leather

My wife and I attended Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate last year. We had a wonderful time and blogged about it here, here and here. One panel discussion we decided to skip was ‘Wanted for Murder: The Ebook’ partly because I’m sick of hearing that print is dead, but by skipping the session, I missed some comments by thriller writer Stephen Leather that would snowball into a scandal that has rocked the publishing world. Regarding publicising his own books on social media Leather said:

My wife and I attended Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate last year. We had a wonderful time and blogged about it here, here and here. One panel discussion we decided to skip was ‘Wanted for Murder: The Ebook’ partly because I’m sick of hearing that print is dead, but by skipping the session, I missed some comments by thriller writer Stephen Leather that would snowball into a scandal that has rocked the publishing world. Regarding publicising his own books on social media Leather said:

As soon as my book is out I’m on Facebook and Twitter several times a day talking about it. I’ll go on to several forums, the well-known forums, and post there under my name and under various other names and various other characters. You build up this whole network of characters who talk about your books and sometimes have conversations with yourself

What’s most surprising is the brazen way Leather boasted about this. The odd thing about Theakston’s was that the subject the panels were supposed to be discussing was often not interesting enough to sustain the session, so writers drifted off onto other subjects. Perhaps Leather made the admission as he was stuck for something to say and thought it wouldn’t amount to a big deal. He was wrong. Leather’s comments were picked up on by, amongst others, spy writer Jeremy Duns. Duns has made something of a name for himself exposing internet frauds. It was Duns who unmasked RJ Ellory as having written fake reviews praising his own novels online. Ellory made an ass of himself but at least he had the good grace to apologise, unlike Stephen Leather. Through dogged research Duns began to identify the ‘sock puppet’ accounts on Facebook, Amazon and Twitter that Leather set up to plug his own work and engage in cyberbullying. By the way, take a look at Leather’s author website. Skim through the pages and you’ll see photos of him with George W Bush, Tony Blair, Chuck Norris, Michael Schumacher etc. They’re obvious parodies, and all harmless fun you might say, but I can’t help thinking they tell us something about Leather’s delusions of grandeur. Nick Cohen, who had a hand in exposing Johann Hari’s articles as full of fabrications, wrote about Leather in his column for the Observer. Cohen’s argument is that American writers who engage in this sort of fraud and plagiarism find they can never get published again, whereas in Britain their careers go on relatively unhindered as with Leather and Hari. Leather reported Cohen to the Press Complaint’s Commission, not for saying that Leather had set up sock puppet accounts, he had already admitted to that, but for Cohen’s write up of Duns findings regarding the cyberbullying of Steve Roach:

When he wanted to fake an identity, Leather picked on Steve Roach, a minor writer who had made disobliging remarks about one of his books. Leather created Twitter “sockpuppet” accounts in the names of @Writerroach and @TheSteveRoach. Roach described on an Amazon forum how one account had “16,000 followers all reading ‘my’ tweets about how much ‘I’ loved SL’s books”. He was nervous. He told Duns in a taped conversation that Leather was “very powerful” and not a man to be crossed. Roach emailed Leather and begged to be left alone. Pleased that his cyber bullying campaign had worked, Leather graciously gave Roach control of the @Writerroach account he had created, to Roach’s “great relief”.

The PCC adjudication was in Cohen’s favour. As Cohen says there is a difference between promoting your own work, which is legitimate, and deceit, which is not. I use this blog to promote my own work quite regularly, whether people choose to buy my books or not is up to them, but I’m not out to deceive anyone. Incidentally, I have come across a rather intriguing authorship question in my research pertaining to James Ellroy. But I don’t regard anything in that example to be fraudulent or malicious, rather it is just a common creative technique employed by novelists. Judge for yourself. Anyway, Duns has reason to believe that there may be many other authors engaged in internet fraud:

I have also heard from authors about private web forums and Facebook groups where authors, some of them extremely successful, hang out, and that they trade positive reviews and also post negative reviews to sabotage authors who they dislike or whose success they feel threatens theirs. I guess we’re looking at the tip of the iceberg here.

I think we owe a great deal to Cohen and Duns for their exhaustive efforts to expose these frauds and not back down when they receive an onslaught of abuse for doing so. If you are a writer and don’t believe this issue is important then I suggest you read these words of Duns:

Please don’t say this is all a car crash, or getting silly now, or it takes two to tango, or aren’t we equally to blame for talking about this while these frauds just carry on merrily deceiving people. Especially if you are more famous than Leather. Get off the pot. Speak out: share, retweet, blog.

Take a stand.

I take it Stephen Leather will not be invited to speak at Harrogate again this year, as Val McDermid is chairing the programming committee this time and as she is one of the signatories of a letter to the Telegraph condemning fake reviews I doubt he will be, but it would be nice if Jeremy Duns was, perhaps in a panel titled ‘Wanted for Fraud: Unmasking the authors who write fake reviews of their own work online’. Now that would be worth going to see.

A student’s take on Vera Caspary’s Laura

This semester I’m teaching two courses for the University of Liverpool’s Continuing Education: The Female Dick: Women in Crime Fiction and Star-Crossed Lovers in Literature. But instead of having my students write traditional essays, I’ve asked them to write blog posts. Why? There are two reasons: first, I think the blog is a great platform to discuss, debate, inform and analyse (if they simply wrote it as an essay for their tutor, it wouldn’t reach as wide an audience), and second, most of my students are entirely new to blogging. Many of them are retired, and they bring a wealth of professional and practical insights to the text.

This semester I’m teaching two courses for the University of Liverpool’s Continuing Education: The Female Dick: Women in Crime Fiction and Star-Crossed Lovers in Literature. But instead of having my students write traditional essays, I’ve asked them to write blog posts. Why? There are two reasons: first, I think the blog is a great platform to discuss, debate, inform and analyse (if they simply wrote it as an essay for their tutor, it wouldn’t reach as wide an audience), and second, most of my students are entirely new to blogging. Many of them are retired, and they bring a wealth of professional and practical insights to the text.

I’ve posted the first, a review of Vera Caspary’s Laura, on Prevailing Westerlies. If you have time to leave a comment, word of encouragement or question, I’m sure it would be appreciated.

Unpublished James Ellroy Interview

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing James Ellroy four times: on three occasions by telephone and once in his apartment in LA. Three of these interviews are included in the collection Conversations with James Ellroy which I edited for University Press of Mississippi. The interview I excluded from the volume was the third telephone interview which took place in November 2008. After giving the matter some thought, I decided that the interview wasn’t up to the high standard of my other interviews with Ellroy. You have to make some very difficult decisions when you’re editing an anthology of this kind, and I wanted to ensure there was space in the book for some of the outstanding interviews Ellroy has given throughout his career to such figures as Duane Tucker, Paul Duncan and Craig McDonald. However, I came across the interview again recently when searching through an old thumb drive, and I thought there were enough interesting moments to share it with you here, published for the very first time. I’ve edited it down quite significantly to the highlights:

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing James Ellroy four times: on three occasions by telephone and once in his apartment in LA. Three of these interviews are included in the collection Conversations with James Ellroy which I edited for University Press of Mississippi. The interview I excluded from the volume was the third telephone interview which took place in November 2008. After giving the matter some thought, I decided that the interview wasn’t up to the high standard of my other interviews with Ellroy. You have to make some very difficult decisions when you’re editing an anthology of this kind, and I wanted to ensure there was space in the book for some of the outstanding interviews Ellroy has given throughout his career to such figures as Duane Tucker, Paul Duncan and Craig McDonald. However, I came across the interview again recently when searching through an old thumb drive, and I thought there were enough interesting moments to share it with you here, published for the very first time. I’ve edited it down quite significantly to the highlights:

INTERVIEWER: I watched Zodiac last night. My wife and I watched it with the director’s commentary, and I was thinking you’ve been involved in a lot of documentaries, factual shows, well Murder and Mayhem, Bazaar Bizarre, the Zodiac DVD commentary. Why the change…

ELLROY: Bazaar Bizarre is just a horrible movie and a horrible performance on my part. I was coming off a crackup and taking some bad medication and my weight was up. I didn’t look good. It’s a bad, vile movie. Why mince words?

INTERVIEWER: I was wondering, you moved from your early fiction where there were lots of motifs about serial killers and murderers, psycho-sexual murderers, but then you moved into more factual explorations of serial killers. Why the move from fiction to factual interpretations?

ELLROY: Well… It started out with the bridge between those two types of works The Black Dahlia, which has the psycho-sexual aspect and the historical aspect in the King of psycho-sexual Los Angeles crimes, and the King of LA crimes period. And it was at that time that I determined to write the LA Quartet. And hence first LA history and then American history, and I have been synchronous ever since. And there may be some psycho-sexual aspects to individual crimes within a larger set of crimes in a given book of mine, but I will never write exclusively in that vein. I determined that I had taken it as far as it would go.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, I’ve been reading Scene of the Crime: Photographs from the LAPD Archive, and it has very haunting photos. Very strange experience to look over those photos of Elizabeth Short, which are of course shocking. Your explanation as to the treatment, well, the torture of her body, and what happened to her hinges a lot on a kind of art, aestheticism, the Victor Hugo novel The Man Who Laughs and the painting. Is that something out of your research on the case or are you interested in any links between art, aestheticism and murder?

ELLROY: I made it up and what happened. And then subsequently, oddly, the writer named Steve Hodel who wrote the book Black Dahlia Avenger— he’s a former LAPD homicide detective– where he posits that his physician surgeon father did the job to imitate the art of Man Ray. It’s a quasi-factual book: it purports to be real, but it’s entirely theoretical and suppositional. But Black Dahlia Avenger made that connection. What a man [Ed Beitiks]. He’s a journalist. He’s dead now, may he rest in peace, Ed Beitiks told me. It was a very fine but still inadequate explanation of the horror visited upon Elizabeth Short that we’re trying to contain within some kind of reference, cultural reference, artistic reference of the horror inflicted upon her, and no level of detail can do that horror justice. And so the Victor Hugo The Man Who Laughs painting, which doesn’t exist, just came to me out of the blue. Someone told me about the painting as I was preparing the text to the book.

INTERVIEWER: One of the things that was interesting about Zodiac (the film) was the Zodiac case is still officially unsolved, whereas a lot of the issues of crime fiction is the theory that everything connects or everything should connect. How do you explore that question of how everything connects or does everything still connect in things like historical fiction and real life?

ELLROY: It certainly does in real life, and the genius of Zodiac, which I think is one of the greatest American crime films, is that nothing ever quite fits and the three men, the three obsessive men, you know the Ruffalo, Gyllenhaal and Downey characters, simply go on and endure in not knowing. And when they know to whatever extent that they know, I’m talking about the scene with Ruffalo and Gyllenhaal in the diner at the end. So what? The guy’s not killing anyone else, and he’s still out on the loose working in a hardware store. And I was haunted by the movie. It influenced a TV pilot that I’m working on now about, although it’s not about the serial killers at all it’s about the cops and the Hillside Strangler task force, and I give Zodiac in the composure and the stillness and the quietude of that movie every credit.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, yes it’s a great movie. I very much enjoyed it.

ELLROY: Very slow isn’t it? It’s just boom.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, it takes its time– and just great performances. I guess on the theory that everything connects, there’s now that quite famous line in your first novel Brown’s Requiem which, I’m gonna have to paraphrase because I don’t have the book right in front of me, when Brown is in Mexico and spots a suspect presumably by chance, he said ‘This was odd. It’s proof of the existence of God.’ With the other references to God in your books, they’re rather ambiguous: Lloyd Hopkins very often prays to a God he admits that he doesn’t believe in. Do you think there is a presence of God in your literature?

ELLROY: Yeah I do. I do and I’m a Christian. I’m not an Evangelical Christian, but God and religious spiritual feelings always guided me during the worst moments of my life, and I don’t for a moment doubt it. Blood’s A Rover is the fullest expression of people from 1968 to 1972 including a woman who’s a Quaker activist pondering the existence or non-existence of God and talking about the nature of belief. And I always like getting in asides and putting it out there and stopping just short of preaching.

INTERVIEWER: There’s been a lot of criticism of your work, in my eyes completely unjustified, but you know people like Mike Davis in his book City of Quartz, a kind of unusual history of Los Angeles, he seems to think the racism of the characters by extension makes the author or the text racist. How would you respond to criticism like that?

ELLROY: Well the racism of protagonists in my book, the actual men that you’re supposed to dig, is a casual attribute, it’s not a defining characteristic. And most people who decry racism, most PCers want racism distilled in that manner. It’s defining, thus it’s indicted, and so casual racist asides from Jack Vincennes or Bud White or Buzz Meeks or Danny Upshaw or Pete Bondurant or, you know, Dwight Holly or any of these guys flummoxes people. And I don’t write from grievance. I’m not out to change the world. I would hope that my being would serve to influence them in some minor way, but I got no beef. And I write stories that are contained within plot boundaries, circumscribed arcs of time. People can think what they like. And I don’t engage in criticism of other writers for a couple of reasons: one, I’m too competitive and I don’t go on panels for the same reason. I’m out to take over the show rather than have a collegial chitchat. And so criticism like the criticism Mike Davis levied at me just, while it bugged me in the moment, goes in one ear and out the other. There are people out there they live on grievance, and I can understand why, and I’ve just gotta say ‘God bless em.’

INTERVIEWER: Your portrayals of LA in the forties and fifties of course the narrative relies not just on either third person or first person but FBI transcripts, newspaper articles, sleazy Hush-Hush tabloids. Why the use of these, you know, other means of communication or telling the story?

ELLROY: To update the actions of the characters outside of their limited viewpoint. Entirely to further the story from a different viewpoint. In the case of White Jazz, to alleviate the burden of the extreme language and update the reader simply from the slant that the protagonists have not seen.

INTERVIEWER: Another thing that may be linked to communication is the portrayal of institutions: the FBI, the CIA, the Mafia. Some illegal, some governmental institutions, and in the Underworld USA, their interests often overlap. How do you render concisely, and where do you get this inspiration for these incredibly complex and convoluted institutions?

ELLROY: Part of it’s just having lived through the era and having soaked up a good deal of doublespeak. A lot of it’s instinct. I’ve never had the instinct to do a great deal of research. I want coherent facts in front of me as I like to extrapolate. A lot of this overlap of agency and obfuscatory talk and the jockeying of men, I’m talking about the political books, aligned with various bogus male authority derive from my reading of Libra.

INTERVIEWER: Yes Libra is a fascinating novel, and I just recently read Don DeLillo’s Underworld. Would it be an inspiration on The Cold Six Thousand?

ELLROY: No, I actually read it after I wrote The Cold Six Thousand. I also think it’s very, very pretentious and flawed. I think it’s a great, great novel, at times I thought this is the greatest novel I ever read. But God does he go on! Did you find that, he just goes on?

INTERVIEWER: Yes, definitely. It’s rather unusual some segments like the nuns and the…

ELLROY: The nuns go nowhere don’t they? I wanted it to stay with the baseball. Yeah and the baseball changing hands, and then it just kept going here, here, here and here and felt more and more undisciplined.

INTERVIEWER: I quite liked Lenny Bruce, the comic monologues which link the story. Would you say that Lenny Bruce and his kind of insult comedy, his highly and wildly adrenalised, neurotic schtick. Was that an inspiration for Lenny Sands?

ELLROY: No, I just liked the idea of Lenny as a name with no dignity. And I also think that Lenny Bruce was nowhere near as good as the monologues that Don DeLillo wrote for him. I mean DeLillo wrote those monologues. He didn’t say that shit. I guarantee you he did not say that shit. I guarantee you he was not that smart and omnivorously gifted. I mean he was a dope fiend who was entirely hit and miss.

INTERVIEWER: I guess a lot of what makes the monologues so fascinating in Underworld is that they’re caught in the moment, particularly around abut the Cuban missile crisis everyone thought they were gonna die in a nuclear holocaust and in the monologues he plays off that fear

ELLROY: The story American Tabloid is entirely inspired by Libra and DeLillo’s tripartite theory: Mob, renegade CIA, crazy Cuban exiles. It’s the line in the prologue ‘Only a reckless verisimilitude can set that line straight.’ And it’s so diligently about the inner lives of the assassins that it creates empathy. YOU WANT JACK DEAD. You want Jack dead because you dig these guys and you’re in their head. It’s only after the fact that I think most people, most people who liked the book think, Oh shit. Why do I feel such great empathy with those who killed John F. Kennedy?

INTERVIEWER: Yes, yes, that is unusual and the ending with the cancer victim Heshie. His death creates this empathy with the death of JFK as well.

ELLROY: ‘Don’t nod out Hesh. You don’t get a show like this every day.’ Pete tells him, yeah.

INTERVIEWER: The history of Los Angeles, it’s your birthplace it’s intensely romantic to you. You’ve lived in a fair few places in in the US: New York, Connecticut, Kansas City. Do any of those settings particularly inform or inspire your writing?

ELLROY: I’m from LA, and it’s a life sentence. As a fount of inspiration, I can write about LA wherever I find myself. LA was what I first saw and I’ll take it. I’ll take it. I have an instinct in this stage of my life to get to places that are a little bit more peaceful and we shall see.

Conversations with James Ellroy is available to buy on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk.

Blogs of the Year 2012

I’m delighted that J. Kingston Pierce of The Rap Sheet has selected the Venetian Vase as one of the best blogs of 2012. It was only last year that David Mattichak (check out his blog here) nominated me for the Very Inspiring Blogger Award and now this! The Blog of the Year 2012 award was started by The Thought Palette and the rules are as follows:

1. Select the blogs you think deserve the “Blog of the Year 2012” Award.

2. Write a blog post and tell us about the blogs you have chosen–there’s no minimum or maximum number of blogs required–and “present” them with their award.

3. Please include a link back to this page, “Blog of the Year 2012” award at The Thought Palette, and include these “rules” in your post.

4. Let the blogs you have chosen know that you have given them this award and share the “rules” with them.

5. You can now also join the Facebook group–click “like” on this page, “Blog of the Year 2012 Award” Facebook group, and then you can share your blog with an even wider audience.

6. As a winner of the award, please add a link back to the blog that presented you with the award–and then proudly display the award on your blog and sidebar.

Chris Routledge and I started VV back in 2009 and it’s been a joy to do. I tend to blog about what research I’m doing at the moment, what I’m reading or just to plug my own books! It can be hard work coming up with enough material to keep people coming back to the site, but when they leave positive comments, subscribe, link back to my work or select VV for awards like this one, it makes the whole thing worthwhile. Sometimes I’m stuck for something to write about and then an idea starts to grow and the urge to write about it is too hard to resist. Another pleasure of blogging is that WordPress gives you excellent porn (stat porn that is). Most visitors to this site come from, unsurprisingly, English speaking countries, but VV also gets plenty of hits from France, Germany, Sweden, Spain etc. It’s nice to know that people from far afield visit the site. I also occasionally get hits from random countries like Saudi Arabia where, I imagine, crime and detective fiction is probably illegal.

I enjoy blogging, and as long as people find the site entertaining, I’ll continue to do it. No blogger will get very far unless he reads other blogs to keep up with what’s going on: it’s both a source of inspiration and a means of learning the craft. Below is a list of blogs which have delighted me that I’d like to name as ‘Blogs of the Year 2012’ (I’ve limited my selection to genre fiction/true crime related blogs, oh, and some of these blogs have already been named as Blog of 2012 but I’m sure they won’t mind winning twice!):

James Ellroy’s 1984 Interview for Armchair Detective

Regular readers will know that last year saw the release of Conversations with James Ellroy, a collection of interviews with the Demon Dog of American crime fiction which I edited for University Press of Mississippi. When I was editing the anthology one of my tasks was to contact writers and publications to obtain the copyright for interviews I wanted to go in the book. Many fans of James Ellroy admire his 1984 interview with Duane Tucker for Armchair Detective. It shows a young, ambitious crime writer with just a few novels to his name but with a clear vision and talent that in the years to come would make him one of America’s greatest crime writers. Here’s an excerpt in which the young Ellroy talks about his future writing plans:

Regular readers will know that last year saw the release of Conversations with James Ellroy, a collection of interviews with the Demon Dog of American crime fiction which I edited for University Press of Mississippi. When I was editing the anthology one of my tasks was to contact writers and publications to obtain the copyright for interviews I wanted to go in the book. Many fans of James Ellroy admire his 1984 interview with Duane Tucker for Armchair Detective. It shows a young, ambitious crime writer with just a few novels to his name but with a clear vision and talent that in the years to come would make him one of America’s greatest crime writers. Here’s an excerpt in which the young Ellroy talks about his future writing plans:

Ellroy: I’m going to write three more present-day L.A. police novels, none of which will feature psychopathic killers. After that, I plan on greatly broadening my scope. How’s this for diversity: a long police procedural set in Sioux City, South Dakota, in 1946; a long novel of political intrigue and mass murder in Berlin around the time of Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch; the first complete novelization of L.A.’s 1947 “Black Dahlia” murder case; and the reworking, rethinking, and rewriting of my one unpublished manuscript—“The Confessions of Bugsy Siegel,” an epic novel about the Jewish gangsters circa 1924–45.

As it happens Ellroy wrote two more ‘present-day L.A. police novels’ and only one of the other novels he mentioned came to fruition, but it would be one of his most powerful works of fiction – The Black Dahlia. Naturally I wanted this interview to be included in the book, and I contacted Duane Tucker to obtain copyright permission. However, Mr Tucker informed me that he had no recollection of conducting the interview and suggested Ellroy may have written it himself and used his name. Intrigued, I contacted Ellroy about this and received a reply from his assistant that ‘like his friend Duane Tucker, James has no recollection of the interview’. Ellroy and Tucker are close friends, and Ellroy dedicated his novel Killer on the Road to him. Armchair Detective is out of print now, but its editor in 1984 was the legendary Otto Penzler. I contacted Mr Penzler about the interview, and he was very adamant that a ‘fake’ interview would not have been published. His explanation was that Mr Tucker simply forgot about the interview as it has been nearly three decades. In the end I obtained the copyright without any difficulties, the interview was published in the collection, and I addressed the authorship question regarding the Tucker interview in the introduction.

It’s not an unusual practice for authors to write their own interviews: Norman Mailer wrote one as a conversation between himself and a Prosecutor in court and the Guardian did a whole series on the subject back in 2010. However, in both those cases, the author is well established and the reader is on the joke. Could Ellroy have written the Tucker interview as a way of announcing himself to the crime fiction world in the early 1980s? As I say in Conversations with James Ellroy, there is no definitive proof that he did, but circumstantially there is enough to suggest that he may have done. For instance, throughout the interview the word icon is consistently misspelled with a k, ikon. This spelling has appeared in several Ellroy novels. Also, the introduction to the interview describes Blood on the Moon as ‘contrapunctually-structured’. This unusual term was coined by Ellroy to define how Blood on the Moon switches from the perspective of the detective to the serial killer and back again. Now if Tucker transcribed and wrote the interview, then why does it feature these conspicuous spellings which are so quintessentially Ellrovian? The more I read the interview, the more I found the interaction between Tucker and Ellroy to appear staged. However, I make no definite claims. It’s every researcher’s worst nightmare to be caught out, AN Wilson style, and there could just be a reasonable explanation for all this.

Still, it’s a fascinating interview, and perhaps it gives us even better access into Ellroy’s mind as a writer than we previously thought. So, if you didn’t get the Christmas present you wanted last month why not pop over to Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk and treat yourself to a copy?

Johnny Stompanato and James Bond

In his review of Sir Sean Connery’s book Being a Scot, Euan Ferguson laments that Connery’s decision to write a book on the subject of Scottish identity, rather than a straight autobiography, means we will never hear his account of ‘the impossibly other-age story of his on-set headbutting of feared Mafia hitman Johnny ‘Stompy’ Stompanato’. Before he shot to fame as James Bond, Connery was making the film Another Time, Another Place (1958) with Lana Turner in London. Stompanato, an enforcer for Los Angeles’ Mob Kingpin Mickey Cohen, was Turner’s boyfriend at the time, and when rumours began to circulate of Connery and Turner having an affair, Stompanato flew to London and, so the story goes, threatened Turner and Connery with a gun, only to have Connery wrestle the gun from him and beat him up. A few months later, Stompanato was killed by Turner’s fourteen-year-old daughter Cheryl Crane. Crane stabbed him to death, so it is believed, in a heated moment when he was threatening her mother. Connery was in LA at the time filming Darby O’Gill and the Little People and had to go into hiding as Cohen suspected he was involved in the luckless Stompanato’s death.

As Ferguson suggests, the whole fascinating, sordid little story sheds light on a bygone Hollywood era. But it was only when I was reading the memoir of another onscreen James Bond, Sir Roger Moore’s My Word is my Bond, that I discovered Moore had his own frightening encounter with Stompanato around the same time as Connery. Moore had been friends with Lana Turner ever since they starred together in the historical drama Diane (1956). While she was in London filming Another Time, Another Place, Turner invited Moore to a party where the confrontation happened:

As the guests arrived, Lana pinned a label on them, mine read ‘Roger Boy Knight’, in reference to Ivanhoe of course. One of the other guests was a rather swarthy individual who carried the label ‘Johnny Dago’. I actually saw very little of him during the evening, which progressed from drinks to food to more drinks and music to dance…

At some point, as the other guests started to thin out, Lana asked me to dance – not one of my talents I must admit. As I shuffled around the floor with her in my arms, probably standing on her toes several times, I felt a cold breeze on the back of my neck. I glanced over my shoulder to find ‘Johnny Dago’ leaning against the doorjamb and staring, unsmilingly, at Lana and me.

A little voice in my head said, ‘Roger it is time you went home!’ I didn’t need a second prompt. I excused myself and made for the door.

A few weeks later I read that ‘Johnny Dago’ – better known as gangster Johnny Stompanato, with whom Lana was romantically involved, having recently divorced Lex Barker – had been deported by Scotland Yard for having physically abused Lana, and for having entered the UK illegally using a passport in the name of John Steele. He had, I read further, also turned up on the set of Lana’s film and threatened Sean Connery with a gun. Sean wrestled the gun from him and decked him with a right hook: all very Bondian. Johnny was convinced that Sean was having an affair with Lana, also very Bondian.

Moore’s encounter with Stompanato was not quite as heroic as Connery’s, but it is interesting to surmise how Stompanato’s rage must have been building step by step, first in his encounter with Moore and later Connery. Both men would achieve massive success as cinema’s greatest hero – James Bond. As Moore said, the whole affair was ‘all very Bondian’. Moore also had another interesting encounter with a gangster, this time Mickey Cohen:

I once met Cohen at a nightclub where I had gone to see the great Don Rickles, a fantastic comedian who became known as the ‘master of the insult’. Gary Cooper was also there that night, and Rickles, having made a few cracks at Cooper and then dismissing me for being a pretty boy at Warner Brothers, turned his attention to Cohen. He called him a dirty hood, then – obviously thinking better of it – dropped on his knees and held his hands together in a prayer towards the gangster, saying that he was only joking and he loved MISTER Cohen SIR!

If you thought Connery was brave taking on Stompanato, then you’ve got to admit Rickles was pretty damn brave calling Cohen a ‘dirty hood’ to his face!

I’ve never read Being a Scot: it struck me as an acquired taste, but I would highly recommend My Word is my Bond as a fascinating insight into a life well lived. The only false note is Moore’s constant dismissal of his talents. Sir Roger’s self-deprecating sense of humour is part of his charm of course, but it does get a little wearing for those of us who enjoy his work.