The First Detective Novel

Last week, NPR in the US ran an interview with Professor Paul Collins, in which host Scott Simon asked “Who wrote the first detective novel?” Collins came up with an answer, The Notting Hill Mystery, published in 1862, by a writer known as Charles Felix, whose real name was Charles Warren Adams. Collins has spent some time unravelling Charles Warren Adams’s identity, and the history of his book. He gives a little more detail in an article in Sunday’s New York Times Book Review:

“The Notting Hill Mystery,” published with illustrations by George Du Maurier (the grandfather of Daphne), was extraordinarily innovative. It is presented as Henderson’s own findings — diary entries, family letters, depositions of servant girls, even a chemical analyst’s report. Its crime-scene map and reproduced “evidence” were ideas that wouldn’t gain currency again until the 1920s. The book is both utterly of its time and utterly ahead of it. Symons, writing in 1975, admitted it “quite bowled me over.”

Victorian reviewers felt the same way. The Guardian found it “very ingeniously put together,” and The Evening Herald hailed its genius, declaring, “The book in its own line stands alone.” The one mixed appraisal shows a reviewer grappling for the first time with just what a detective novel is. “The Notting Hill Mystery,” according to The London Review, was “a carefully prepared chaos, in which the reader, as in the game called solitaire, is compelled to pick out his own way to the elucidation of the proposed puzzle.”

Charles Felix quickly issued a Christmas gift book called “Barefooted Birdie” and the unremarkable novel “Velvet Lawn.” Another novel appeared so briefly that the British Library now holds one of only four known copies. And with that, the inventor of the detective novel vanished like the killer in a locked-room mystery.

Until Now.

The Notting Hill Mystery is available from the British Library as a Print on Demand facsimile edition, via Amazon.

The System in the Works of George V. Higgins

My Christmas reading included George V. Higgins’ wonderful debut novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1972). I’m not sure if I would include Higgins as one of my favourite crime writers, but he is definitely one of the most innovative and challenging crime writers of the twentieth century, so much so that his work can be difficult to read. The plot, or what there is of it, centres around aging small-time criminal Eddie ‘Fingers’ Coyle. Coyle wants to leave ‘the life’ but is roped into a deal by the young gun-runner Jackie Brown. Meanwhile, the police are putting pressure on Coyle to rat out his friends, a.k.a criminal associates, in order to guarantee his freedom, a proposition that weighs heavily with Coyle’s longstanding old-school criminal code.

The novel is technically written in a cold and impartial third-person narrative, as evidenced in the famous opening line, ‘Jackie Brown at twenty-six, with no expression on his face, said that he could get some guns’, but a huge amount of the text is comprised of dialogue, and Higgins is a master at recreating the working class Irish and Italian dialects of Boston, Massachusetts, the novel’s setting. The criminal characters tend to be loquacious, and as a consequence they talk a lot of BS. The challenge to the reader is where in the novel we can discern dialogue which is driving the plot as opposed to places where the characters are giving verbose distractions. But what is most challenging about Higgins’ work is how the novels conclude with only a partial sense of resolution. The ramifications of the crimes will go on and on and characters will continually pass through the complex and unwieldy legal system, as one prosecutor says towards the end of the novel:

Some of us die, the rest of us get older, new guys come along, old guys disappear. It changes every day.

It might be tempting to view this cynical depiction of police work and the legal system as deeply depressing, but Higgins is not portraying a system of institutionalised brutality, ingrained corruption and punitive unworkable laws as found in the work of Eddie Bunker. Higgins was a lawyer and a college professor. He knew the intricacies of the legal system and despite laying bare its cumbersome and flawed features, there is still a sense of reserved conservative optimism in his work. The wheels of justice keep turning, somewhat ineffectively but never to the extent that it will ever stop working, and to a certain degree this mirrors the human relationships of Higgins’ characters. As David Mamet, another American writer who is a master at telling stories almost entirely through dialogue, argues in his rather controversial, very playful essay, Why I Am No Longer a ‘Brain-Dead Liberal’.

I’d observed that lust, greed, envy, sloth, and their pals are giving the world a good run for its money, but that nonetheless, people in general seem to get from day to day; and that we in the United States get from day to day under rather wonderful and privileged circumstances—that we are not and never have been the villains that some of the world and some of our citizens make us out to be, but that we are a confection of normal (greedy, lustful, duplicitous, corrupt, inspired—in short, human) individuals living under a spectacularly effective compact called the Constitution, and lucky to get it.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle was adapted into a classic crime film directed by Peter Yates and with Robert Mitchum in the title role. George V. Higgins died of a heart attack in 1999, one week before his sixtieth birthday. The George V. Higgins archive is housed at the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina.

Classic Spoofs: Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid

Well, Christmas is upon us and I thought something lighthearted would be fun to post considering the time of year. I recently rediscovered Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (1982), Carl Reiner’s spoof of classic film noirs and detective fiction of the 40s and 50s, and I’ve embedded one of the funniest scenes below. There have been many spoofs of film noir, but this one really is unique as Reiner merges contemporary footage of Steve Martin playing private detective Rigby Reardon with footage of actors such as Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney and Alan Ladd from classic film noir’s such as White Heat (1949), The Big Sleep (1946) and This Gun for Hire (1942). In one of my favourite scenes below, Rigby visits Swede Anderson, played by Burt Lancaster in one of the famous scenes in The Killers (1946), but as Rigby is in the kitchen making Swede one of his famous ‘javas’ two gunmen burst into the room. The film is so gloriously silly that it needs to be watched and not explained. Enjoy:

Ellrovian Prose

One of the most striking features of James Ellroy’s most recent novel Blood’s A Rover (2009), is Ellroy’s return to a more eloquent and explicated prose style after the mixed critical reaction to his clipped, sparse style in The Cold Six Thousand (2001). It’s interesting to trace the development of Ellroy’s ‘Ellrovian’ prose style. As a writer who has carefully cultivated his own image or ‘Demon Dog’ persona there is a strong possibility that Ellroy may have coined the term Ellrovian himself– he uses it in his memoir The Hilliker Curse (2010) and also in his correspondence with his publishers (which is available to view at his archive at the Thomas Cooper Library, University of South Carolina).

Ellrovian should be defined simply as ‘in the manner of James Ellroy’, but Ellroy’s first eight novels do not recognisably possess such a unique prose style with which readers have come to associate with the author. Ellrovian prose only became truly noticeable with Ellroy’s ninth novel, LA Confidential (1990), and with that book Ellroy claims it developed almost by accident. Ellroy’s original draft manuscript totalled 809 pages. A senior editor at Warner Books informed Ellroy that the book was too long and needed to be shortened for the sake of publishing costs. Ellroy decided that the narrative was too intricately and precisely plotted to delete any scenes and thus went through the manuscript page by page and sentence by sentence to remove extraneous words. By doing this he reduced the length of the manuscript by over two hundred pages without losing a single scene.

For a novelist whose work is often described as cinematic its interesting to note how this truncated prose style in the novel of LA Confidential is even more sparse and less descriptive than the screenplay to the 1997 film adaptation of LA Confidential. Below is the scene from the novel where Bud White rescues Inez Soto and shoots dead her kidnapper, Sylvester Fitch:

A nude woman spread-eagled on a mattress – bound with neckties, a necktie in her mouth. Bud hit the next room loud.

A fat mulatto at a table – naked, wolfing Kellogg’s Rice Krispies. He put down his spoon, raised his hands. ‘Nossir, don’t want no trouble.’

Bud shot him in the face, pulled a spare piece – bang, bang from the coon’s line of fire. The man hit the floor dead spread – a prime entry wound oozing blood. Bud put the spare in his hand; the front door crashed in. He dumped Rice Krispies on the stiff, called an ambulance.

The screenplay’s version (below) seems much more descriptive and slower in pace for the same scene:

INT. BEDROOM

A nude girl (INEZ SOTO) spread-eagled on a mattress. Bound and gagged. Her eyes grow wide at the sight of Bud, then flicker down the hall. Directing him.

INT. HALLWAY – DAY

Raising the .38, Bud continues along the hall. He looks into an empty kitchen. Up ahead…

INT. LIVING ROOM – DAY

SYLVESTER FITCH sits naked on the couch wolfing Rice Krispies and watching cartoons on a flickering TV. He looks up, sees the .38 before he sees Bud beyond it. Fitch sets down his spoon.

Bud shoots him in the face. Dead, Fitch just sits there.

Bud moves behind him. Pulling a spare piece from his ankle holster, Bud fires back at the door from Fitch’s line of fire, then puts the gun in Fitch’s hand.

We hear a crash against the front door. As Fitch slides off the chair to the floor, Bud dumps the Rice Krispies on him.

The prose style would continue to develop in Ellroy’s next novel, White Jazz (1992), which is told from the first-person perspective of Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klein. The writing style is even more truncated and telegraphic than LA Confidential and reflects Klein’s panicked, confused voice. Also Klein is narrating events many years after they took place and he is in the grip of a fever dream, the fractured, dissipated style reflects his unreliabilty as a narrator:

All I have is the will to remember. Time revoked/fever dreams – I wake up reaching, afraid I’ll forget. […] Fever – that time burning. I want to go with the music – spin, fall with it.

Ellroy would develop an interesting variation on this prose style in his short stories and novellas. In the short story ‘Hush-Hush’ published in G.Q. magazine in 1998, events are narrated by the tabloid magazine Hush-Hush columnist Danny Getchell. Getchell speaks entirely in alliterative and onomatopoeic sentences. He seems incapable of saying a word without following it with four or five other words beginning with the same letter:

I alakazammed to Allah, genuflected to Jesus, and called out to that cat the kikes call God. I said I’d keester communists and bash ban-the-bombers, and dig up dirt on that dowager dyke Eleanor Roosevelt. I’d donate dough to a Moslem mosque. I’d put in with Pat Boone, wear white buck shoes, and warble at a Billy Graham Crusade. I wouldn’t print my piece on Rabbi R.R. Ravitz and that Hebrew-school Hannah he humped last Hanukkah.

This makes for challenging reading which occasionally veers into tedium. It’s not often that I would say anything Ellroy has written is dull, but some of his short stories have their dull moments. Getchell does come up with one killer punchline to explain his speech patterns:

I told him how my meshugenah mom mistreated me. She only let me read one book: a thick thesaurus.

It was not until the publication of The Cold Six Thousand that Ellroy would face severe criticism for his use of Ellrovian prose. The language is more staccato and pared down than in any preceding novel, but it is far more uncompromisingly dry than the colourful and surreal narration of Klein in White Jazz. Ellroy has since admitted that he took the style too far. The novel is difficult to read but immensely rewarding. As a reader you have to brace yourself to the fact you are going to see the story from the perspective of racist and amoral characters. In an interview with Craig MacDonald, Ellroy described the first two sentences of the novel as a warning. They read:

They sent him to Dallas to kill a nigger pimp named Wendell Durfee. He wasn’t sure he could do it.

It’s fair to say that Ellroy took the more extreme aspects of Ellrovian prose as far as it could go in The Cold Six Thousand, and his return to a more accessible style is exciting and welcome. For a hint at what Ellroy’s next novel Perfidia will be like, the first of four novels which will be a prequel to the original LA Quartet, take a look at Los Angeles Magazine’s latest interview with him. It seems we will be seeing the young Dudley Smith fall in love with a certain nurse named Geneva Hilliker!

CSI Hertfordshire

There is a very funny story in the Evening Standard today about how two police officers arrived at a house in Baldock, Hertforshire where a drug dealer had been held hostage by gang members. By the time the police arrived, the kidnappers, who had ordered pizza, were gone but the delivery boy was on their doorstep with the pizzas. The quick-thinking delivery boy offered the pizzas to the officers at a reduced rate. And they proceeded to eat the evidence while the kidnappers were at large and place the boxes in the boot of their car, not realising the boxes contained the phone number of the kidnappers on the delivery slip. Nice to know these guys are keeping our streets safe! You can read about the whole funny episode here.

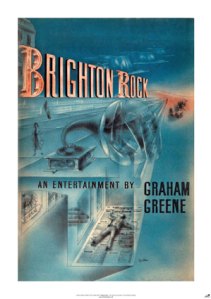

Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock

Chris Pak is currently studying for a PhD at the University of Liverpool. He specialises in Science Fiction, with a thesis focused on the theme of terraforming, but is also interested in other Fantastic and Genre Fictions. He teaches several undergraduate modules at the University of Liverpool and is scheduled to begin teaching a new module on Noir writing in early 2011. More information, and links to other essays and reviews, can be found at www.chrispak.webs.com.

Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock (1938) is a disturbing novel revolving around the murder of a newspaper personality, “Kolly Kibber” (Fred Hale), who distributes business cards as clues in a competition challenging the public to identify him and report his whereabouts for prize money. The calculated atmosphere of paranoia at the novel’s opening disorients the reader; attempts to put together the circumstances surrounding the fear Hale experiences during his assignment to Brighton soon gives way to the no less mysterious question of his relationship to an unnamed young man who he appears to know and dread. We later learn that he is Pinkie Brown, the young, cruel leader of a local gang. After Hale’s murder the self-righteous Ida Arnold, who meets Hale for the first time just before he is killed, sets out to investigate what to her is the suspicious report claiming that Hale died of a heart attack. As the novel develops, the narrative alternates between Brown and his further efforts to cover his tracks while maintaining his farcical relationship with Rose, and Arnold’s amateur yet persistent investigation of Brown and his involvement in Hale’s murder.

Brown tries to eliminate all evidence of his gang’s involvement in Hale’s murder, but his relative youth and inexperience lead him to overcompensate. Perhaps the most striking aspects of the novel are its gritty portrayal of Brown’s ambivalent relationship with Rose, a waitress whom he marries so as to prevent her from testifying against him, and the decline in strength and influence of Brown’s gang under his leadership. Theirs is a marriage of convenience; Brown struggles with the idea of murdering her and with his sympathetic yet abortive affection for her throughout their short and troubled relationship. The naive Rose turns out to be less than completely innocent and, regardless of her suspicions, chooses to marry Brown in rebellion against her domineering family and against her Catholic background, an upbringing that she has in common with Brown. Brown, on the other hand, is revealed as a less experienced gangster than this reader expected. He comes up against the sophisticated mob boss Mr. Colleoni, who moves into the power vacuum vacated by Brown’s mentor (the previous leader of Brown’s gang) and establishes supremacy over the corrupt world of Brighton.

The novel is named for the famous Brighton Rock candy which, Arnold claims, she resembles: ‘“I’ve never changed. It’s like those sticks of rock: bite it all the way down. That’s human nature”’. Hard and merciless, cheap yet sweet, Brighton Rock stands as a symbol for Brown and Arnold’s (among others’) lack of compassion, for the squalid life led by many of these characters amidst a town of booming luxury and for Brown’s failure to adapt to new circumstances. Brighton Rock has been adapted for film in 1947 by John Boulting, with a remake by Rowan Joffe scheduled for release in February 2011.

By Chris Pak

Crime Film Remakes and Unfinished Projects

Crime Fiction fans have a lot to look forward to from upcoming films: Rowan Joffe’s adaptation of Brighton Rock is out in U.K. cinemas in February 2011, HBO have just released the trailer for their mini-series adaptation of James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce, John Le Carre’s classic Cold War novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is being filmed and is due for release next year and all three novels of Stieg Larsson’s Millenium trilogy are to be made into films directed by David Fincher. Now if there is one thing that puts a damper on these projects it is that they are all remakes of brilliant, some might say unsurpassably brilliant, films and television series. The Boulting brothers 1947 adaptation of Brighton Rock is perhaps the greatest British film noir ever made. The original BBC production of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy captured the tone and essence of Le Carre’s work better than any other film adaptation of Le Carre’s novels ever did. Do either of these productions need to be remade? There is nothing to say a remake can not be as good or even better than the original version: John Huston’s critically lauded adaptation of The Maltese Falcon was actually a remake (or if you prefer reinterpretation of Dashiell Hammett’s novel) of an earlier adaptation starring Ricardo Cortez. Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely was filmed as the awful The Falcon Takes Over in 1942, but was later very successfully adapted in 1944 and 1975. But even with this in mind, there is still something about the upcoming remakes which is a little dispiriting. Wouldn’t it be better to see film versions of the as yet unfilmed Le Carre novels, The Night Manager and Our Game rather than sit through another production of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy? There is also filmmaking etiquette being breached with these remakes. In an interview with Word and Film, Niels Arden Oplev, the director of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, expressed anger that Hollywood is remaking the Millenium trilogy so soon after the original. Fincher’s first adaptation has gone into production before we in the UK have had a chance to see the Swedish version of The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest. Will the story be as interesting the second time around? Will Rooney Sara be anywhere near as good as Noomi Rapace’s stunning and definitive portrayal of Lisbeth Salander? I guess we’ll just have to wait and see.

There is one thing that makes me more excited about these remakes than I might otherwise have been, and it is that I now see that a project controlled by my favourite creative artists might not necessarily be any better. Some time ago I wrote of how the Hannibal Lecter franchise plummeted in terms of quality after the book and film of The Silence of the Lambs. So recently I thought it would be fun to read David Mamet’s rejected screenplay adaptation of Thomas Harris’ Hannibal. David Mamet is widely regarded as an outstanding playwright, screenwriter and director (and his novels are pretty good too), and while the film adaptation of Hannibal was terrible, I had long entertained the notion that it could have been really good had they used his original script. But then I sat down to read Mamet’s rejected screenplay on the dailyscript.com, and to my horrorI found it to be risibly bad. The action is stilted, the plot is driven by endless dialogue and the tone is obscure and arty. The Italian characters are offensive stereotypes and mutter dialogue as cliched as ‘buya lot of pasta for your wife.’ It’s not all bad, in fact it comes to life when Mamet is daring and deviates from the book. The controversial final ‘dinner’ scene is allusive and subtle, much better than the disgustingly explicit scene in the film. As the script really only comes alive when Mamet is tearing up the source novel, it makes me wonder if being a purist when it comes to books and films is largely futile, and I should be more enthusiastic about these coming remakes. It’s better to see these films getting made than money being lost on unproduced projects. Another fascinating screenplay to read online is the Carnahan brothers bizarre adaptation of James Ellroy’s White Jazz. The entire script is, like the novel, written from the first- person perspective of Dave ‘the Enforcer’ Klein (right down to Klein describing and directing the camera angles). It’s one of the most unusual scripts you’ll ever read, and it’s a terrible shame it was never made into a film.

Tony Hancock and The Missing Page

I’m currently tweaking a manuscript I’m about to submit, so I haven’t had much time for blogging. However, I would like to share something I’ve recently rediscovered via YouTube. When I was a kid, my parents owned several videotapes of the British comedian Tony Hancock’s classic sitcom Hancock’s Half Hour. As a child, I never thought an old black and white comedy show would appeal to me, but one day I put one into the VCR and watched a few episodes such as ‘The Blood Donor’, ‘The Two Murderers’ and ‘Twelve Angry Men’. I was immediately hooked. There was something incredibly funny, but also touching and sad about the buffoonish and pompous Hancock. Playing an exaggerated version of himself, and aided by wonderful scripts by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, Hancock is always desperate for some kind of artistic or establishment recognition but is constantly frustrated or upstaged by his laid-back friend and lodger Sid James.

As this blog is about crime fiction, I’d like to refer you to one of the very best episodes, ‘The Missing Page’ from 1960. The episode begins with Hancock at his local library declaring to the librarian that he has read almost every book they have in stock. He manages to get a hold of a copy of the pulp thriller, Lady Don’t Fall Backwards by Darcy Sarto (the only other book he wants to read, Lolita, is always out on loan). Hancock is gripped by the mystery whodunnit featuring suave New York Detective Johnny Oxford, but to his horror when he gets to the end of the book he discovers the last page is missing, along with Johnny Oxford’s unveiling of the murderer! It’s up to Hancock and Sid James to solve the mystery of Lady Don’t Fall Backwards, but will they prove as good at detective work as Johnny Oxford? You can watch a clip from ‘The Missing Page’ below, and the entire episode is available for viewing on the WorldofTonyHancock YouTube page. In my opinion, fifty years after it was first broadcast the humour still holds up well. And unlike many spoofs of crime fiction, it actually captures the joy of reading a crime novel and playing armchair detective:

The real life Tony Hancock was a sad and tragic figure. He brought laughter and joy to millions of people and deserves his reputation as one of Britain’s best post-war comedians, but he was also self-destructive and betrayed every friend and colleague he had. He committed suicide at the age of forty-four, an alcoholic and celebrity exile living in Australia. I’d recommend Cliff Goodwin’s biography When the Wind Changed: The Life and Death of Tony Hancock (2000) as a fairly comprehensive and heartbreaking account of his life and demise.

How Many Crime Writers Are Internet Trolls?

The rapid expansion of blogs, online discussion forums and comment threads in recent years has revolutionised social networking and how people connect with each other throughout the world. But it has also given birth to a new phenomenon, the Internet Troll. The definition of an internet troll is still vague, but Wikipedia describes a troll as ‘someone who posts inflammatory, extraneous, or off-topic messages in an online community, such as an online discussion forum, chat room, or blog, with the primary intent of provoking other users into a desired emotional response or of otherwise disrupting normal on-topic discussion.’ A troll can be, depending on your opinion, a foul-mouthed timewaster or a mischievous prankster. As blogging has become almost obligatory for any crime writer who wants to promote their work, there have arisen a number of interesting cases of crime writers who have resorted to a bit of trolling. Let me start with a comparatively mild example, and one that assumes you can be a troll on your own website. James Ellroy has been known as the Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction for years, and this persona has served him well in interviews through which he has often created and refined myths surrounding his work. Ellroy has never used a computer in his career– or even a typewriter. He writes everything in longhand and this is then typed up by his assistant. His Facebook page, however, is very lively, and Ellroy often sends messages through his assistant to post on there. Shortly before the publication of Blood’s A Rover, Ellroy posted this ‘status update’:

Achtung, Fuckheads! We are now one month and eleven days away from the publication of my greatest masterpiece, “Blood’s A Rover”. It will hit stores on September 22, published by Alfred A. Knopf. It is written in panther pus, napalm, jaguar jizz and blood!!!!! Be prepared to uproot your entire lives when this book makes the scene!!!!! (Hat-tip to J. Kingston Pierce)

Those who are unfamiliar with the Demon Dog persona might be willing to dismiss Ellroy as a neo-nazi on the basis of these remarks. But his outrageousness is deliberately exaggerated to provoke shock in the reader, and hone his reputation as America’s most brilliant and out-there crime novelist. Of course, edgy humour only works when you’re very careful to get the tone right. One example of trolling which came back to haunt a crime writer was when Philip Kerr, author of the Bernie Gunther novels, wrote a scathing review on Amazon of Allan Massie’s The Royal Stuarts: A History of the Family that Shaped Britain. Kerr was motivated by revenge as Massie had written two bad reviews of Kerr’s recent novels. He was civil enough to confess to this at the end of the review:

Good manners and honesty prompt me to mention that Alan Massie has reviewed my last two novels with a distinct lack of enthusiasm. For the first review I say good luck to him. If he didn’t like my book, then that’s fair enough. He’s entitled to his opinion which is that I can’t write for toffee. Maybe I can’t.

He should however, have excused himself from reviewing me a second time. In my opinion that’s bad manners. I’m of the opinion that authors should avoid reviewing the books of their peers and, usually, I stick to this principle, but I’ve made a special exception in Mister Massie’s case. . .

Kerr wrote the review on the Amazon page probably because no newspaper would have accepted something so overtly bitter. Perhaps he thought he could vent his anger on Amazon as the review might get buried amongst the thousands of other online reviews (it has since been taken down), but when the Telegraph broke the story, Kerr looked very foolish.

These are two examples of crime writers engaging in a bit of trolling, although if readers know of any others please let me know. Perhaps crime writers are suited to trolling because of their understanding of mystery narratives and the desire to embrace new forms to create mystery and mischief in the online age, but as with the case of Kerr, we should remember that not every famous literary troll will be well received.

Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles

The blog Hidden Los Angeles has a post on Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles, along with some great film clips, including the one below, from a documentary on the subject. There isn’t much here that dedicated Chandler fans won’t already know about him, but the old footage and some interesting anecdotes about policing and Los Angeles in the 1930s and 1940s, make this worth watching:

Visit Hidden Los Angeles for more.