Bond Directors at their Best

There’s a lot of online debate as to who was the best actor to play James Bond. There’s a lot less, I suspect, as to who was the best director the Bond series ever had. I don’t intend to try and answer that question here, but I do want to draw attention to the directors who worked on some of the early and middle films. Dating back to the time when Pierce Brosnan revived the series as Bond, the convention has been to use a different director from film to film. The exceptions would be Martin Campbell, who directed two films, and Sam Mendes, who is currently directing his second. When the Bond series began, most of the directors helmed several films each, and thus set a fairly consistent tone for the series. Terence Young directed three films, Guy Hamilton four, Lewis Gilbert three and John Glen holds the record with five. Below I’ve embedded a clip and brief description of some of the best work of Young, Hamilton, Gilbert and Glen. I’ve tried to find scenes which exemplify the romanticism and fantasy of the series, some of which I think has been lost with recent emphasis on torture and Daniel Craig’s moody, introspective Bond.

Thunderball (1965) – Terence Young

As Fiona Volpe, Luciana Paluzzi played the greatest villainess the series has ever seen and her demise, a dance of death with Sean Connery’s Bond only a few hours after they sleep together with ‘the gun […] under the pillow the whole time’, is a wonderfully playful and wicked scene. Paluzzi retired from acting in the 1970s after never quite making the front rank, another example of the Bond girl curse. Such a shame. She was certainly one of the most compelling and sexiest actresses to have appeared in the series.

You Only Live Twice (1967) – Lewis Gilbert

Lewis Gilbert directed three of the most spectacular films in the Bond series: You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and Moonraker (1979). There were times when the spectacle swamped the creativity, such as in the Amazon boat chase in Moonraker when Bond is simply pushing the buttons on his gadgets to take out the bad guys. At his best though, Gilbert could perfectly convey the escapist fantasy of the series, such as in this scene from You Only Live Twice when Bond visits the Kobe docks with the Japanese agent Aki and ends up being pitted against a seemingly endless series of henchmen. I love the moment when the fight moves to the rooftop and the camera pans away to capture the full breadth of the scene. Magic.

Live and Let Die (1973) – Guy Hamilton

Guy Hamilton directed two Sean Connery Bond films– Goldfinger (1964), Diamonds are Forever (1971)– and two starring Roger Moore, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). Perhaps the greatest moment from his four films comes in Live and Let Die: when Bond finds himself surrounded by crocodiles, he has to employ an inventive method of escape. Even the unflappable Roger Moore looks scared near these things and bear in mind no stuntman would ever be asked to do this today. It wouldn’t be quite as impressive with CGI crocodiles that’s for sure:

Licence to Kill (1989) – John Glen

Ok, ok, Licence to Kill was the film that ushered in much of the sadistic violence of the later films. Still, it was Glen’s fifth consecutive Bond film and the last film he directed in the series. It’s a film that still possesses some of that old movie magic. I can just imagine how the screenwriters came up with this scene: ‘We start with Bond shooting a guy on a boat, then he jumps underwater while the bad guys are shooting at him, has a fight with some scuba divers and escapes by water skiing behind a plane. Then the plane takes off with him holding onto the wings, he climbs inside throws out the bad guys and is on his way. Got that?’

The opening scene of the first episode of The Devil’s Crown (1978) begins with a shot of Henry II‘s tomb at Fontveraud Abbey, Anjou. Sonorous narration declares:

Henry, by the grace of God, King of England, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine and Count of Anjou. Eight feet of ground doth now suffice for whom the earth was not enough.

Alas, burial would be an apt metaphor for this remarkable BBC drama about the early Plantagenet kings, as it was to disappear from view and was believed lost for years.

I have always regarded the early 1970s to the mid-1980s as a Golden Age of British television drama. Just look at the number of classic dramas that were produced in that period: Elizabeth R, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, The Shadow of the Tower, I Claudius, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (a personal favourite), Smiley’s People, The Jewel in the Crown, Edge of Darkness and The Singing Detective to name just a few. And then there are the character-actors who appear, to quote Richard Dawkins out of context, with all the ‘likable familiarity of senior partners in a firm of Dickensian lawyers’. Actors such as Peter Vaughan, Sian Phillips, Bernard Hepton, Charles Kay and Terence Rigby. Of course, there have been many brilliant dramas since the mid-1980s. But I think in later years, a certain conservatism set in. The BBC started to produce more and more Dickens and Austen adaptations, which all feel very safe. Looking back at the Seventies (I was born in the early Eighties mind you) TV drama just seemed more radical, daring and exciting. It’s probably no coincidence that the Seventies was an era when the British film industry collapsed and seemed to churn out nothing but sleazy sex comedies (do you remember such classics as Confessions of a Window Cleaner and Adventures of a Plumber’s Mate?), and some of our best creative talent would have flocked to TV. Indeed, parallels are striking today with the decline of Hollywood and rise of American TV channels, such as HBO, producing knock-out television.

A year or two ago, I had just finished watching a copy of the superb To Serve Them All My Days (1980). Impressed by John Duttine’s performance in the leading role, I looked up what other roles he had played. One title stuck out on his resume: The Devil’s Crown in which he played King John. At first I couldn’t find out that much about the series. The information online was minimal and at that time the episode titles on the BFI and IMDB were incomplete. The show had never been repeated or released on DVD and was listed in some sources as lost. All I could find were comment threads where people shared their memories of the show and this scratchy recording of the theme tune on YouTube. I was stunned that a major BBC drama from the late Seventies could be lost because the information that was available on the show was very intriguing. The Devil’s Crown was an epic 13 episode drama series covering the Angevin kings, Henry II, Richard the Lionheart and King John. The cast was impressive and read like a who’s who’s of thespians from British film and television: Brian Cox, Charles Kay, Jane Lapotaire, Michael Byrne, Jack Shepherd, Thorley Walters and the aforementioned John Duttine. I kept an eye on the comment threads from time to time in the hope that a copy might resurface. Then the Wikipedia page was updated to say that the BFI had a copy that was available for viewing on request. I was just about to make arrangements to visit the BFI when – a miracle! – all thirteen episodes were uploaded online by some benevolent YouTube user. The following review is based on my viewing of the drama on YouTube, but I’m not going to link to it because that will increase the chances that some killjoy will have it taken down. The upload appears to have been taken from a broadcast on French television. All of the credits are in French, but thankfully there are no French subtitles or dubbing. According to the chap who uploaded it, someone has been peddling poor quality bootleg DVD copies, but I really think it’s about time The Devil’s Crown became available through the BBC Shop, and a full television repeat is also overdue.

The Devil’s Crown begins with England ravaged by Civil War in the period known as The Anarchy. Henry Plantagenet (latterly Henry II), played with boundless charm and energy by Brian Cox, sees his opportunity to seize the crown and create a kingdom of law and order. He cuts a deal with King Stephen in which Stephen will name him his heir, excluding his sons Eustace and William in exchange for a fragile truce. Stephen’s sudden death elevates Henry to the throne. He may have been King of England, but the bulk of the Angevin Empire was in modern day France, and it was this that Henry regarded as the Jewel in his Crown, maintained through a series of political marriages and complex allegiances. Henry pays homage to Louis VII, King of the Franks, for these lands, but it is clear that Henry is the shrewder and more ambitious of the two kings, having married Louis’ ex-wife Eleanor of Aquitaine. This is a complex story to render on screen and there was a wonderful book The Devil’s Crown: Henry II and his Sons by Richard Barber which was written in conjunction with the series to clarify many of the political intricacies. Barber does a good job of separating fact from fiction in the Medieval period, but some of the myths (or should I say debatable points?) such as Eleanor’s ‘Court of Love’ are kept in the TV series as they make for good drama. This allows the writers to embellish the role of the famous troubadour Bertran de Born, played with wonderful worldly cynicism by Freddie Jones.

The Devil’s Crown begins with England ravaged by Civil War in the period known as The Anarchy. Henry Plantagenet (latterly Henry II), played with boundless charm and energy by Brian Cox, sees his opportunity to seize the crown and create a kingdom of law and order. He cuts a deal with King Stephen in which Stephen will name him his heir, excluding his sons Eustace and William in exchange for a fragile truce. Stephen’s sudden death elevates Henry to the throne. He may have been King of England, but the bulk of the Angevin Empire was in modern day France, and it was this that Henry regarded as the Jewel in his Crown, maintained through a series of political marriages and complex allegiances. Henry pays homage to Louis VII, King of the Franks, for these lands, but it is clear that Henry is the shrewder and more ambitious of the two kings, having married Louis’ ex-wife Eleanor of Aquitaine. This is a complex story to render on screen and there was a wonderful book The Devil’s Crown: Henry II and his Sons by Richard Barber which was written in conjunction with the series to clarify many of the political intricacies. Barber does a good job of separating fact from fiction in the Medieval period, but some of the myths (or should I say debatable points?) such as Eleanor’s ‘Court of Love’ are kept in the TV series as they make for good drama. This allows the writers to embellish the role of the famous troubadour Bertran de Born, played with wonderful worldly cynicism by Freddie Jones.

Henry’s first real test as king comes from his former friend Thomas Becket (Jack Shepherd). Elevating Becket to Archbishop of Canterbury from his position as Lord Chancellor seems at first to Henry to be a canny decision. It soon backfires when Becket starts using the Church as a rival power to the Crown. This is a daring portrayal of the Henry/Becket feud. Other depictions I have seen, such as the 1964 Becket with Richard Burton in the the title role, have portrayed the Archbishop as becoming pious and devout in office, ultimately achieving martyrdom for his faith. Jack Shepherd plays Becket as malevolent and power-hungry, hellbent on trying to keep the Church above the law. Upon Henry’s death Richard the Lionheart (Michael Byrne) succeeds him and this is where, in my opinion, the series starts to flag. A huge amount of screen time explores Richard’s reputed homosexuality, nothing wrong with that per se but it only seems to contribute to Richard’s endlessly sullen, introspective and unreliable character. Byrne is a good actor but he struggles to make this Richard interesting. There are still compensations in these middle episodes. Zoe Wanamaker has a wonderful early role as Richard’s neglected wife Berengaria of Navarre and when Richard is on Crusade there is one of the most quietly effective scenes of the whole series. Richard fails to take back Jerusalem from Saladin and his Saracen warriors. A truce is negotiated whereby Crusaders and Christian pilgrims are allowed to visit the holy city, but Richard doesn’t go thinking that he only wants to walk into the city having taken it back from Saladin. Lying in his bed, weak from disease, he imagines one of his soldiers visiting the city. We then cut to a monologue by a Crusader describing the city. What makes this scene truly brilliant is that although we are interested in historical fiction to see how life was different in the past we are also interested in how it was similar to life now. The Crusader of the scene could be a loquacious working class man of the present day and his monologue is all the more interesting in that he describes the city in colloquial, unfussy language before ending with his disappointment that they never took it back for Christendom. Richard quietly sobs, just as heartbroken that he has let down this man as much as he has failed God. The final episodes focus on the disastrous reign of King John. By this time Louis VII has been succeeded by his much more ambitious and cunning son Philip II (Christopher Gable), who is determined to rid France of Angevin influence. John has developed a reputation for evil in popular culture and this is how he first appears in the show, a libertine coveting power to dispel his nickname of John Lackland. His brutal revenge on the young rebellious Arthur, Duke of Brittany is reminiscent of Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. Gradually though John becomes more sympathetic. The collapse of the Angevin Empire had become inevitable even before his reign but naturally he gets the blame for it. Unlike his brother or father however John has a sincere love of England, and his defeat at Philip’s hands, forcing him out of France, only serves to reinforce his love of a country his ancestors regarded as a nation of serfs. The events surrounding the signing of Magna Carta also provides much intrigue. It has long been claimed that John never intended to honour the terms of the Great Charter, but The Devil’s Crown shows how the Barons had never expected him to sign anyway and, knowing this, John decides to sign to wrongfoot them.

You might think having waited so long to see The Devil’s Crown I would either be inevitably disappointed or slightly biased to believing the show is a lost classic. Truthfully, I would rank The Devil’s Crown among the very best of television dramas that were made in the period. It’s compelling, intriguing and often moving. Brian Cox himself described the show as ‘very ahead of its time’. However, there are flaws, and not just the lull in the episodes focusing on Richard which I mentioned. Memorably, all historical TV dramas during this period were shot on set, even the exterior scenes. The BBC just did not have the money to stage big battles or build convincing sets of castles and the like. It could lead to some imaginative storytelling as the sets were quite malleable. On being told that Louis VII has married Constance of Castile, Henry, then in Normandy, sees it happening before his eyes on the same set. There are downsides. For some outdoor scenes they simply paint the floor green and the walls blue. A modern audience especially might find this jarring. The Devil’s Crown may have been commissioned following the success of I Claudius, indeed there are some striking parallels between the two stories. A wise and mostly benevolent monarch Henry II/Augustus is undermined during his long reign by his scheming and cunning wife Eleanor of Aquitaine/Livia who strongly favours her son for the succession Richard/Tiberius who ultimately is more suited to soldiering than leadership and has a brief and unhappy reign. The parallels only go so far, however, as Eleanor of Aquitaine is just not as malevolent as the arch-villainess Livia. There were several historical dramas made during the period that tried to follow the I Claudius model of political intrigue and murder in a Royal Court. The Borgias and The Cleopatras were both panned for being lurid as they lacked the benevolent central character that Derek Jacobi’s Claudius provided, the stammering, much-mocked boy who grows up to become historian and Emperor. The Devil’s Crown also suffers a little in comparison to I Claudius, but ultimately it’s a drama that deserves to be judged on its own merits of which there are many. This is a fascinating rendering of a very complex and brutal period of history. I’m delighted to have seen it after first hearing of it a few years ago. It now belongs to television history. I hope that it finally reaches the wider audience it deserves.

American Psycho: The Novel With a Killer Soundtrack

I finally read Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho (1991) earlier this year. It had been on my bookshelf for ages, but I was rather intimated by its reputation for gory violence, so I put off reading it. Friends of mine who read the novel said it made them feel physically sick. Anyway, having read it, I can see why American Psycho is considered such a brilliant work, but I did feel Ellis went too far with the gory images. Patrick Bateman is an investment banker in late 1980s New York. By day he obsesses over his routine, which seems to include very little working and mostly indulging his taste for clothes, drugs and fashionable restaurants. Bateman’s string of consciousness narration can go on endlessly about these things and to the most minute detail. There’s a great deal of black humour here. Bateman and his colleagues swagger around like pre-Revolutionary French Aristocrats. There is another side to Bateman that he hides from his colleagues and from his fiancee. Whether he is acting the role of a yuppie or that of a serial killer, Bateman seems to be the walking embodiment of the banality of evil. Be warned, this novel is not for the squeamish, and it tends to get more violent as it goes on. There is a startling twist in the conclusion (which I won’t give away here). I will say,however, it’s not the sort of twist that throws attention from one suspect to another, but rather one that questions the status of the entire text. It’s what you might call Keyser Soze syndrome, although American Psycho was published four years before Soze appeared (or did he?) in The Usual Suspects. Reading this novel after the 2008 economic crash only adds to it prophetic feel, although perhaps Ellis’ negative view of Wall Street and consumerist society is just too simplistic.

For me, the highlight of the novel was the short essays on Bateman’s favourite pop groups– Genesis, Whitney Houston and Huey Lewis and the News– which appear sporadically in the narrative, although I was left slightly puzzled as to the reason for their inclusion. Was Ellis trying to say that Bateman’s love of music was every bit as shallow and consumerist as his other obsessions (some of Bateman’s musical analysis is hilariously superficial) or does it point to a deeper side to him? According to this essay in The Tech it is definitely the former: ‘Being a vapid soul, he likes only the most vapid bands […] By taking these pop bands so seriously, so analytically, Ellis succeeds in showing just how soulless and transparent these bands are.’ Still, if the essays are deliberately flawed, they are still as well written as anything you would find in a music magazine, and are a joy to read in what can be a gruelling book. Below, I’ve quoted some passages on music from the novel and embedded the relevant group’s music video.

Genesis

My favourite track is “Man on the Corner,” which is the only song credited solely to Collins, a moving ballad with a pretty synthesized melody plus a riveting drum machine in the background. Though it could easily come off any of Phil’s solo albums, because the themes of loneliness, paranoia and alienation are overly familiar to Genesis it evokes the band’s hopeful humanism. “Man on the Corner” profoundly equates a relationship with a solitary figure (a bum, perhaps a poor homeless person?), “that lonely man on the corner” who just stands around.

Whitney Houston

The ballad “Saving All My Love for You” is the sexiest, most romantic song on the record. It also has a killer saxophone solo by Tom Scott and one can hear the influences of sixties girl-group pop in it (it was cowritten by Gerry Goffin) but the sixties girl groups were never this emotional or sexy (or as well produced) as this song is.

Huey Lewis and the News

“Give Me the Keys (And I’ll Drive You Crazy)” is a good-times blues rocker about (what else?) driving around, incorporating the album’s theme in a much more playful way than previous songs on the album did, and though lyrically it might seem impoverished, it’s still a sign that the new “serious” Lewis – that Huey the artist – hasn’t totally lost his frisky sense of humour.

Two Eurosceptic Thrillers

The controversial appointment of Jean-Claude Juncker as President of the European Commission brought to mind two novels I read recently. Both could be described as Eurosceptic thrillers and feature the European Union greatly increasing its powers through the office of an EU President. I first wrote about Eurosceptic crime fiction for the British Politics Review and examined this increasingly promising genre through the works of conservative writers such as Andrew Roberts, Michael Dobbs and Alan Judd. Since then, I’ve been on the lookout for anti-EU novels by authors on the other side of the political spectrum. I’ve haven’t quite found them, but I have discovered an interesting diversity of opinion, i.e. degrees of Euroscepticism.

Firstly, we have the Icelandic thriller Vulture’s Lair (2012) by Hallur Hallson. The 2008 economic crisis was particularly severe in Iceland, and their poor financial state prompted Iceland’s political class to discuss the possibility of joining the EU. This prospect seems to have filled Hallson with dread. Set in a dystopic future where the Icelandic Republic has been abolished and become a mere province in the ‘Great European Empire’, Vulture’s Lair includes a myriad of sub-plots, which mostly revolve around Krummi, a patriotic fisherman who begins the narrative making a minor protest in Brussels against EU regulations. Krummi is eventually spurred on to uncover a vast conspiracy with parallels to the assassination of JFK.

Perhaps something is lost in translation, although its impressive to think that one in ten Icelanders have written and published a book, but I struggled through large sections of this novel. Hallson seems much more at ease propagating nationalism than other Eurosceptic writers I have read, and the novel is just bogged down by too much preachy flag-waving. That being said, there are some wonderfully diverting passages on Icelandic poetry and folklore, and the plot really picks up to an exciting climax if you can wade through the first two-thirds.

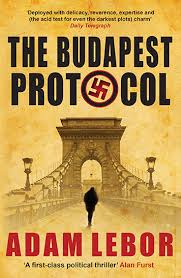

Do you remember Nigel Farage’s ill-judged comments about people not wanting Romanian neighbours? Adam Lebor’s The Budapest Protocol (2009) provides a nice antidote to them. Another dystopic thriller set in a Europe where the EU has greatly increased its power and the first directly elected President of Europe holds crypto-fascist views, Lebor wrote The Budapest Protocol to highlight the plight of the Romani or Roma people in Central Europe. Indeed, a donation of every copy sold goes to the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims in Torture. In the novel, Alex Farkas is a British journalist based in Hungary, much like Lebor. After the murder of his grandfather, Farkas begins to investigate a conspiracy centered round the titular document, which turns out to be an agreement signed by Nazis in the last days of the Second World War to create a Fourth Reich through a new economic empire (if you think that’s far-fetched read some of Lebor’s research on this issue). Part of the narrative concerns sinister plans to implement a mass sterilisation of the Romani population under the guise of being a fingerprinting program. Lebor is a writer who writes movingly and sympathetically about ethnic minorities. The appendix documents real cases of abuse against the Roma people including sterilisation.

Do you remember Nigel Farage’s ill-judged comments about people not wanting Romanian neighbours? Adam Lebor’s The Budapest Protocol (2009) provides a nice antidote to them. Another dystopic thriller set in a Europe where the EU has greatly increased its power and the first directly elected President of Europe holds crypto-fascist views, Lebor wrote The Budapest Protocol to highlight the plight of the Romani or Roma people in Central Europe. Indeed, a donation of every copy sold goes to the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims in Torture. In the novel, Alex Farkas is a British journalist based in Hungary, much like Lebor. After the murder of his grandfather, Farkas begins to investigate a conspiracy centered round the titular document, which turns out to be an agreement signed by Nazis in the last days of the Second World War to create a Fourth Reich through a new economic empire (if you think that’s far-fetched read some of Lebor’s research on this issue). Part of the narrative concerns sinister plans to implement a mass sterilisation of the Romani population under the guise of being a fingerprinting program. Lebor is a writer who writes movingly and sympathetically about ethnic minorities. The appendix documents real cases of abuse against the Roma people including sterilisation.

All in all, two very interesting Eurosceptic thrillers. Although if any readers could highlight some more examples from this small but growing genre I’d like to hear from you.

Birthday Blog

WordPress have notified me that it has been five years since Chris Routledge and I started the Venetian Vase together. At first the stats were low. It wasn’t until I wrote a piece on the wonderful book A Friendship: The Letters of Dan Rowan and John D. MacDonald 1967-1974 that we started to build a readership, and I began to see blogs were a great place to publish original research. Thanks to everyone whose either been regular reader or just dropped by, and here’s to the next five years.

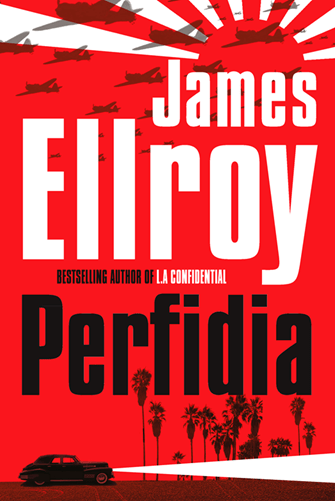

Perfidia – New Video on Front Cover

A regular reader has alerted me to this cool video of how Print Club London have created screen prints for James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia. Note that this is different, and I would argue better, artwork than the front cover I blogged about back in March:

And here is the finished cover:

James Ellroy: The Poet in the Porno Bookstore

Perhaps it’s a sign of old age, but I’m looking forward to reading the critical reaction to James Ellroy’s new novel Perfidia almost as much as I’m looking forward to reading the novel. Ellroy has always been a canny writer in generating critical interest. On the one hand he is a wild man figure, the Demon Dog of American Crime Fiction decked out in garish Hawaiian shirts, spouting outrageous right-wing views and howling like a dog. And yet to many critics his writing transcends the crime genre and becomes something much more powerful. In France, his books are read as social commentary, and his deep knowledge of poetry is all too often overlooked despite frequent poetic allusions in his novels.

Ellroy’s skill as a publicist has been to merge these two roles, so the reader, critic or interviewer will never quite know how he will react and whether or not he is being sincere, or performing, or both. In his essay ‘Where I Get My Weird Shit’, Ellroy describes a period in the mid-1970s when his search for creative inspiration coincided with some of his worst experiences of drug and alcohol abuse:

I read books and shagged epigrams and insights. T.S. Eliot. Highbrow shit. “We only live, only suspire, consumed by either fire or fire.” A classy fuck flick: The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann.

The Eliot quote, taken from ‘Little Gidding’ in Four Quartets, was to be the epigram of Ellroy’s unpublished novel ‘LA Death Trip’. The novel was extensively rewritten and re-titled Blood on the Moon (1984), with the Eliot epigram dropped in favour of a quote from Richard II. The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann (1974) was a hardcore porn film directed by Radley Metzger and starring Barbara Bourbon in the eponymous role. I will leave it to Ellroy to describe the plot to you:

Pam Mann’s a horndog. She’s a passive punchboard and a seductress. She’s a nympho candide. She’s the poster girl for ‘70s excess. She fucks half of New York City in one day and comes home to fuck her husband. He’s the best. She really loves him. Her day was satire and a goof on inclusion. Sex is everything and nothing.

I haven’t seen the film (you’ll just have to take my word on that), but I have read up on it and there is a further twist (no pun intended) to the ending which I won’t reveal here. One of Ellroy’s first jobs was at the Porno Villa Bookstore, but he was fired after stealing from the till. Really, when you can’t trust pornographers what’s the world come to? Let’s assume Ellroy came across The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann while he was working at the Porno Villa. It clearly left an impression on him, not just due to the ample charms of Barbara Bourbon, but because it was a memorable film with a strong story. Years later, he would weave the themes of pornography and voyeurism into his work. There are innumerable examples from his novels. The snuff film which features in the second Lloyd Hopkins novel Because the Night (1985) is memorably grisly.

The Eliot epigram from ‘Little Gidding’ never appeared in one of his novels; however, a writer as powerful as Eliot could easily influence Ellroy’s work in more ways than a mere epigram. Eliot, incidentally, was a keen reader of crime and detective fiction, so Ellroy’s admiration for him seems apt. As David E. Chinitz wrote in A Companion to T.S. Eliot (2009), Eliot may have preferred genre fiction to more serious, literary forms:

The fiction he (Eliot) admitted to reading was of another sort: the comic stories of P.G. Wodehouse, and the detective novels of Raymond Chandler, Agatha Christie and others. Eliot was in reality no friend of the sacralization of high culture that readers came to associate with him

I believe that the image of Ellroy (even if it is very carefully crafted by the author) working at the Porno Villa and jumping between porn and T.S. Eliot for creative inspiration as he nurtured his dreams of becoming a great crime writer, should appeal to fans of books of all genres.

I have found a trailer for The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann. Apart from the grating narration, it does seem like a very good, Woody Allen-like, film:

Lunchtime Classics

I mentioned in a previous post that I’ll be talking about George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman Papers on Wednesday, August 6th, 1pm, at Waterstones Liverpool One as part of their ‘Lunchtime Classics’ series. Here’s the itinerary of speakers, and works they cover, in the series: All talks begin at 1pm.

Weds 4th June: Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. Presented by Glyn Morgan (University of Liverpool).

Weds 11th June: Exegesis by Philip K. Dick. Presented by Nicole McDonald (University of Liverpool).

Thurs 19th June: House of Suns by Alastair Reynolds. Presented by Dr Will Slocombe (University of Liverpool). In Association with CRSF (Current Research in Speculative Fiction).

Tues 24th June: Butcher’s Crossing by John Williams. Presented by Lee Rooney (University of Liverpool).

Weds 2nd July: Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole. Presented by Bethan Roberts (University of Liverpool). 250th Anniversary Special.

Mon 7th July: Waverley by Walter Scott. Presented by Dr Diana Powell (University of Liverpool). 200th Anniversary Special.

Weds 16th July: The Napoleon of Notting-Hill by G.K. Chesterton. Presented by Leimar Garcia-Siino (University of Liverpool).

Tues 22nd July: Fountains of Neptune by Rikki Ducornet. Presented by Maria Shmygol (University of Liverpool).

James Ellroy and Randy Rice

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, the chances are you read the work of James Ellroy, and if you’re an Ellroy fan, I have a question – have you heard the name Randy Rice? I began my PhD on Ellroy by studying the hundreds of interviews Ellroy has given over the course of his career. One name popped up regularly in Ellroy’s recollections: Randy Rice. Rice was Ellroy’s closest friend during his years of drug and alcohol abuse. They shared many of the same vices, but when Rice got sober this gave Ellroy the confidence to follow his lead. Despite this, I didn’t think Rice warranted much attention in a study of Ellroy. He appeared at first to be merely a footnote in Ellroy’s life. It was only when I was editing Conversations with James Ellroy (2012) that I began to think otherwise. Rice seems to be a ubiquitous presence in Ellroy’s life in the 1970s, and an allusive presence in his early novels, and in this blogpost I’m going to examine the level of his influence on Ellroy.

However, I should confess what I don’t know about Rice. I don’t know his date of birth or what he did for a living (I would guess, like Ellroy, he was unemployed for long periods of time). I’ve not been able to find a photograph, so I’ve no idea what he looked like. All I know for sure is that he was Ellroy’s friend, and this is, I believe, what’s important. Interviewer Paul Duncan described Rice as a ‘childhood friend’ of Ellroy’s, and this French website puts the year they met as 1961. In his second memoir, The Hilliker Curse (2010), Rice pops up briefly when Ellroy describes how he once sold his own blood plasma, got drunk on the money with Rice at the Pacific Palisades, and then woke up days later in bed with a woman who ‘weighed three bills easy’. To make matters more surreal, he discovered he was in San Francisco and had absolutely no recollection how he had got there. In an interview with Martin Kihn, Ellroy describes how he was living on the rooftop of Rice’s apartment building ‘at Pico and Robertson in West Los Angeles’ in 1975 when he began screaming uncontrollably and suffering hallucinations. Rice called an ambulance and, by doing so, may well have saved Ellroy’s life. A doctor diagnosed Ellroy has having post-alcoholic brain syndrome, ironically a consequence of the sobriety Rice had urged him to pursue. In the documentary Feast of Death (2001), Ellroy describes how he invented ‘Dog Humour’ with Rice. Ellroy fans will recognise Dog Humour from his interviews, book readings and even sections of his fiction. It has to be seen to be believed, but I would describe it as Ellroy developing his own schtick by being deliberately provocative and offensive in every conceivable way: sexually, politically, racially. Once every possible taboo has been broken the reader or audience will realise Ellroy is being tongue-in-cheek, relax and enjoy the humour on its own level. To be clear, I enjoy Dog Humor, and I don’t think for a moment that Ellroy is a bigot, although I can understand why some people have jumped to that conclusion.

Rice’s influence on Ellroy in formulating Dog Humour indicates that he was to have a considerable, but until now, unseen effect on Ellroy’s writing career. In an interview with Don Swaim, Ellroy said he and Rice would ‘spend HOURS hashing over the Black Dahlia case and talking about crime fiction.’ In Ellroy’s debut novel Brown’s Requiem (1981), which is dedicated to Rice, the titular character Fritz Brown’s closest friend is an unemployed alcoholic named Walter. For all his flaws, Brown regards Walter as an extraordinary person:

Walter has taken fantasy into the dimension of genius. His is pure verbal fantasy: Walter has never written, filmed, or composed anything. Nonetheless, in his perpetual T-Bird haze he can transform his wino fantasies into insights and parables that touch at the quick of life. On his good days, that is. On his bad ones he can sound like a high school kid wired up on bad speed. I hoped he was on today, for I was exhilarated myself, and felt the need of his stimulus: the power of a Walter epigram can clarify the most puzzling day.

As Ellroy based Brown on himself, there is no doubt in my mind that he based Walter on Randy Rice. At the end of the novel, Walter dies of cirrhosis of the liver and Brown is left devastated. In Ellroy’s second novel, Clandestine (1982), there is a minor character named Randy Rice, a mailman who provides the leading character, Freddy Underhill, with some information pertaining to a murder investigation. However, Rice’s appearance is fleeting and Underhill’s friendship with a fellow police officer who is killed in action may have been more closely based on Ellroy’s friendship with Rice. In an interview Rodney Taveira, Ellroy describes how a visit to the cinema with Rice gave him the inspiration for the character of Danny Upshaw, an investigator who begins to doubt his sexuality, in the novel The Big Nowhere (1988):

Here’s the genesis of Danny Upshaw: my buddy Randy Rice and I went to see the William Friedkin movie Cruising. So he’s a young cop, presumably heterosexual, played by Al Pacino, and there’s gay killings in Greenwich Village circa 1980, pre-AIDS and all that.

AWOL

Apologies for the lack of posts recently. There are lots of things I’m planning to blog about, but I have been swamped with work. Normal service will resume shortly. In the meantime, here are the details of some events I shall be speaking at in Liverpool. All are welcome:

I’ll be talking about James Ellroy to the Liverpool Gender Research Network at the Siren cafe on Sunday, May 18th at 1pm.

As part of their Lunchtime Literary Classics series I’ll be talking about George MacDonald Fraser’s The Flashman Papers at Waterstones Liverpool One on Wednesday, August 6th at 1pm.

I’ll be giving a talk ‘Royal Navy Films of the 1950s: A Voyage Through Post-War Britain’ on Thursday, October 2 at 126 Mount Pleasant, the Centre Lifelong Learning Building, 6:30 pm, and as a follow-up to that I’ll be introducing a screening of the classic war/noir hybrid The Ship That Died of Shame at the same location on Thursday, October 23 at 6pm.

The these last two events require enough people to sign up beforehand in order to go ahead, so if you are interested please contact the Centre for Lifelong Learning and book ahead.

Oh, and my better half will be giving a talk ‘Ice in the Blood: Women in Nordic Crime Fiction’ on May 3oth, 6pm at the Nordic Church and Cultural Centre.