Jean Spangler: Megan Abbott’s Dahlia in The Song is You

With her second novel The Song is You (2007), Megan Abbott takes the case of the unsolved disappearance of 1940s Hollywood starlet Jean Spangler and creates a novel as emotionally powerful, but perhaps not as ambitious in scope, as James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987). The lead character, Gil Hopkins (Hop), is a reporter and Hollywood fixer. Two years after Spangler’s disappearance, Hop is approached by a black actress named Iolene, who claims that he buried evidence important to the Spangler case. Hop had introduced Spangler and Iolene to two movie stars the night Spangler went missing and then had withheld information from the press and gave the cops false leads on Spangler (who had dated a mobster). Now that the Spangler case, which the press dubs ‘The Daughter of the Dahlia’, has fizzled out, Hop begins his own investigation.

With her second novel The Song is You (2007), Megan Abbott takes the case of the unsolved disappearance of 1940s Hollywood starlet Jean Spangler and creates a novel as emotionally powerful, but perhaps not as ambitious in scope, as James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987). The lead character, Gil Hopkins (Hop), is a reporter and Hollywood fixer. Two years after Spangler’s disappearance, Hop is approached by a black actress named Iolene, who claims that he buried evidence important to the Spangler case. Hop had introduced Spangler and Iolene to two movie stars the night Spangler went missing and then had withheld information from the press and gave the cops false leads on Spangler (who had dated a mobster). Now that the Spangler case, which the press dubs ‘The Daughter of the Dahlia’, has fizzled out, Hop begins his own investigation.

A reoccuring theme in the novel is the marking of the female body to symbolise masculinity. Men, including Hop, and society as a masculine audience, are drawn to female characters out of a form of hatred, which leads them to destroy. This is seen in the media’s handling of the Spangler case; they lose interest in her once the mob angle surfaces. As Hop puts it, ‘ So she’s no longer a possible victim of some snazzy sex criminal. Instead she becomes, well, you see it, a two-bit mob whore’. The newspaper’s stance is not only incriminating of itself but also of their audience–with no body, and thus no signs of torture to titillate, readers get bored. Hop’s relationship with his wife Midge also reflects this kind of hate-desire. Even before their marriage falls apart when she leaves him for his good-natured friend, their sex life indicts his masculine urge to destroy the feminine:

Each night he clamped his hand on one of her white dimpled knees and pushed it down flat on the rough hotel sheets and tried to f**k all their shared ugliness away. And all her beauty, too.

For Abbott, the femme fatale has lost her power to seduce, and women have become meat to be abused. That is not to say that Hop is not disgusted by himself and the world he inhabits. His investigation into Spangler’s disappearance becomes as much an emotional investigation of himself. Ultimately, Hop is a better man than the two sexually sadistic movie stars, who are Hop’s prime suspects, and ironically have earned their fame in upbeat Hollywood musicals (playing a Donald O’Connor and Gene Kelly type duo). By comparison, Hop is more transparently flawed and compromised.

The torture-murder of Elizabeth Short and the disappearance of Jean Spangler are connected not only in terms of some of the details of the case, but in The Song is You, Abbott links the two women figuratively through the sexual torture of the female body. With Jean Spangler, Abbott has created a fictional portrayal of an unsolved mystery and unavenged victim that is every bit as haunting and powerful as Ellroy’s now iconic portrayal of the Elizabeth Short murder.

The Unhappy Life of Cornell Woolrich

Cornell Woolrich’s dark crime novels sold well in the 1940s and 1950s, but have not had lasting success. He is now almost unknown outside specialist circles, but his books were nevertheless staples of Hollywood filmmaking in the 1940s and 1950s. Woolrich’s invisible influence on cinema is perhaps why many of the titles are so familiar: The Bride Wore Black (1940), Phantom Lady (1942), Night Has A Thousand Eyes (1945), I Married a Dead Man (1948). Woolrich, with his switchback plotting, and bleak outlook, combined the Gothic sensibility of Edgar Allan Poe, with the dark, urban setting of hard-boiled crime fiction to create what has been called “paranoid noir.” Woolrich’s own life, and in particular his relationship with his mother, was in many ways at least as strange as the plots of his stories.

The trailer for Phantom Lady (1944), directed by Robert Siodmak

Woolrich was born in New York City in 1903. His father was a civil engineer, and after his parents separated, Woolrich spent some time living with him in Mexico, where one of his hobbies was collecting spent bullet cartridges in the street. However, he idolised his mother, Claire Attalie Woolrich, and from the age of 12 he lived with her in New York City. In 1921 he went to Columbia University, where he studied journalism. But during a period of illness, which left him bedridden for six weeks, he wrote a romantic novel, Cover Charge (1926). Encouraged by the success of this he dropped out of college. His second novel, Children of the Ritz (1927), won a $10,000 prize, and was produced as a film by First National Pictures in 1929.

Having moved to Hollywood to work on the script for Children of the Ritz, in 1930 Woolrich married Gloria Blackton, the daughter of a movie producer. The marriage did not last long. Within a few months they separated, probably because Blackton discovered Woolrich’s secret homosexuality, and the marriage was annulled, apparently unconsummated, in 1933. Woolrich, who seems to have enjoyed patrolling the docks dressed in a sailor’s uniform, trying to pick up men, returned to New York, where he moved in with his mother. They lived together at the Hotel Marseilles until her death in 1957. After his own death, 11 years later, Woolrich was buried with her in the same vault.

Partly because publisher Simon and Schuster “owned” the Cornell Woolrich name, and Woolrich wanted to publish elsewhere, many of his novels were written under the names William Irish and George Hopley, and this is one reason why he is less well known than he might be. Woolrich, who was an alcoholic, also became something of a recluse, doing much of his writing in the corner of the hotel room, while his mother sat watching. Following his return to New York, Woolrich began writing stories for the pulp publishers, including Black Mask and Story magazine, ultimately publishing over 250 short mystery stories, a contribution for which he won an Edgar Award in 1948. He won an Edgar Award in 1950 for his contribution to the RKO movie The Window.

It was in the 1940s, when he started writing thrillers, that Woolrich produced his best work, in particular the run of “Black” novels beginning with The Bride Wore Black (1940). In common with many of Woolrich’s plots, The Bride Wore Black involves a race against time during which a bride, whose husband is shot dead on their wedding day, pursues the gunmen, seeking vengeance. The first William Irish novel, Phantom Lady (1942) tells the story of a man convicted and sentenced to death for killing his wife, and the race to find a woman who can provide an alibi. In 1943, Raymond Chandler wrote to Alfred A. Knopf about having read Phantom Lady, and at first wondered who “William Irish” was. When he discovered it was Woolrich, he described him as “one of the oldest hands in the detective fiction business. He is known in the trade as an idea writer, liking the tour de force, and not much of a character man. I think his stuff is very readable, but leaves no warmth behind it.”

Woolrich was a difficult man, who was uncomfortable in company, and could be irascible, unpleasant, and bitter. His stories express a world view that is cynical and pessimistic about human nature. Although homosexuality is never explicitly mentioned in his work, Charles Krinsky notes in his entry for glbtq that in novels such as The Bride Wore Black, and I Married a Dead Man (1948), love, and family life, fail to provide security, safety, or fulfilling relationships. In a Woolrich novel, malice and revenge are the primary motivating forces, and lives are blighted by despair and paranoia. It is because of this that Woolrich has been described as an originator of “paranoid noir,” defined by Philip Simpson in the Blackwell Companion to Crime Fiction as stories of a “persecuted victim, caught up in a deterministic world in which the standard rules have suddenly changed for the worse.” Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945), written as George Hopley, is arguably the archetypal novel of this type.

Woolrich, whose diabetes and alcoholism worsened to leave him disabled, became increasingly embittered. He alienated most of his friends and acquaintances and spent the final decade of his life almost entirely alone. In early 1968 an untreated foot infection developed into gangrene, and led to the partial amputation of his leg. When he died in September that year, Woolrich left his entire estate of around $1 million dollars to Columbia University, where the Claire Woolrich fellowships, named after his mother, continue to support students in journalism and writing.

Tony Blair’s Journey and Robert Harris’ Ghost

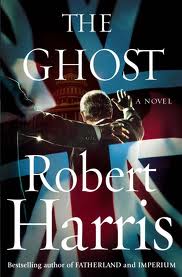

Robert Harris’ political thriller The Ghost is a thinly-veiled criticism of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Harris was formerly a generous donor to New Labour when Tony Blair was the party leader, but during the course of Blair’s premiership, Harris became increasingly disillusioned with Blair and the political party he had donated large sums to from his personal fortune. Above all, Harris found Blair’s partnership with President George W. Bush in the invasion of Iraq unforgivable. Harris wrote The Ghost around the time that Blair stepped down from office in 2007. The novel takes the form of a lengthy memorandum of an unnamed ghost-writer drafting the memoirs of the fictional disgraced former PM Adam Lang. There are some striking parallels between events and characters in the novel and events and people of the Blair years. But what is even more striking are the prophetic elements of the novel, as well as the final irony that the recent publication of Blair’s autobiography The Journey, was not ghost-written. Here are a few parallels between the novel and events in real life:

Robert Harris’ political thriller The Ghost is a thinly-veiled criticism of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Harris was formerly a generous donor to New Labour when Tony Blair was the party leader, but during the course of Blair’s premiership, Harris became increasingly disillusioned with Blair and the political party he had donated large sums to from his personal fortune. Above all, Harris found Blair’s partnership with President George W. Bush in the invasion of Iraq unforgivable. Harris wrote The Ghost around the time that Blair stepped down from office in 2007. The novel takes the form of a lengthy memorandum of an unnamed ghost-writer drafting the memoirs of the fictional disgraced former PM Adam Lang. There are some striking parallels between events and characters in the novel and events and people of the Blair years. But what is even more striking are the prophetic elements of the novel, as well as the final irony that the recent publication of Blair’s autobiography The Journey, was not ghost-written. Here are a few parallels between the novel and events in real life:

The late Robin Cook is the model for the character of Richard Rycart, the former Foreign Secretary of Lang, who is determined to see Lang imprisoned for war crimes.

Lang’s wife Ruth is portrayed as manipulative and scheming, and is unflatteringly based on Cherie Blair.

In the novel Lang is having an affair with his personal assistant Amelia Bly. The character is based on Anji Hunter, who Blair describes as ‘sexy and exuberant’ in his memoirs.

The strongest parallel between novel and reality is clearly the similarities between Adam Lang and Tony Blair, and this is where events since the publication of The Ghost seem to be echoing the novel. In the novel, Lang is holed up in a millionaire’s paradise on Martha’s Vineyard, living the life of a recluse, as he is hated in almost every country outside the United States. Since leaving office, it is widely reported, although never confirmed, that Blair is a non-dom, and can only spend 90 days a year in the country he used to govern for tax purposes. His travels have become almost as dangerous as Lang’s, he was almost pelted with eggs at a Dublin bookstore during a signing for his memoirs, and a visit to a book signing in London had to be cancelled as a result. But the most interesting legacy of The Ghost is that Tony Blair refused to hire a ghost-writer to help him draft his memoirs, and the critical reaction to The Journey has been uniformly hostile. In his review of Blair’s memoirs in The Observer, Andrew Rawnsley describes the prose as ‘execrable’, and the chapters ‘are as badly planned as the invasion of Iraq.’ Not only did Blair refuse a ghost-writer, it seems the book was never even edited. Blair wrote his memoirs in longhand on hundreds of notepads which were then transplanted, word for word, into the finished book. I wonder if the scathing reviews for The Journey are making Robert Harris chuckle, because if it was the success of The Ghost that made Blair decide not to hire a professional ghost-writer, then it was Harris’ last act of revenge on the political leader he once revered.

Zoe Richards and the Louise Paxton Hoax

Some time ago I wrote a post titled YouTube and the Louise Paxton Mystery. It turned out to be one of this site’s most popular posts and is still regulalrly getting hits. It concerned a series of thirty-eight video blogs that I discovered on YouTube, featuring Louise, a young woman from Norwich, who relocates to an apartment in London. The opening videos are uneventful, as they simply show Louise enjoying her new home, but then things start to go wrong. Louise starts to believe she is being stalked by a stranger who may have access to the apartment. Each video becomes progressively more paranoid and creepy, and gradually a supernatural element is woven into the story, until, in the final video, Louise disappears. Louise’ YouTube page has not been updated since her disappearance three years ago and neither has her MySpace page. There is a website dedicated to finding Louise and appealing for any information as to her whereabouts.

It is of course all a hoax, but an unsettling and successfully elaborate one. Since watching the videos, I’ve been waiting for the real Lousie Paxton to come out of the closet (or should I say cellar), and now it seems she has. Louise Paxton is Zoe Richards, an actress with a number of horror movie credits to her name. Here’s the link to her imdb page. The cast and crew of the new horror film The Torment are interviewed in Gore Press. Zoe Richards is part of the cast and confesses she was Louise Paxton in the videos (this forms just a very brief mention in the interview). The director of The Torment, Andrew Cull, also directed the Louise Paxton videos. As far I know, this is the first time that anyone involved in the hoax has gone on record to talk about it, although hats off to this YouTube user who figured out Louise was actually Zoe Richards some time ago.

A lot of the fear element has been removed now that there is no remaining ambiguity that this was a hoax, but you can still watch the Louise Paxton videos and admire the creativity. The entire project was in questionable taste, but then that’s Horror for you!

Update: I had the privilege of interviewing Zoe Richards about her experiences working on the project.

Read More: My interview with writer-director Andrew Cull, who created the Louise Paxton internet mystery In the Dark.

David Fincher’s The Social Network: A Film for the Digital Age or a Facebook Flop?

David Fincher is one of the greatest American film directors working today. His contribution to the crime/suspense genre is stunning, Alien 3 (1992), Se7en (1995), The Game (1997), Panic Room (2002), and his masterpiece Zodiac (2007). But with his latest film, The Social Network, about the founding of the social networking site Facebook, Fincher has moved from away from the crime genre.

I’m somewhat perplexed at this sudden departure. Although to be fair, his previous film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) was a bizarre, oddball project that was critically panned. The Social Network looks like it will receive a far warmer critical reception. Despite the fact that very few critics have seen the film, it is already being described as the film of the decade, a masterpiece, and of course there is the obligatory talk of Academy Awards. Much of this hype stems from the official trailer for the film which defintely falls into a love it or hate it category. I confess that I fall into the latter group. Here’s the trailer:

Am I just completely wrong in assuming this film looks like it will be terrible? When we first see Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg) he states that his ambition is to get into Harvard’s most exclusive clubs. Hardly inspiring; so this is going to be a ‘from riches to even more riches tale’? Then the trailer moves into quite a lot of techno-babble about the creation of Facebook. Zuckerberg talks about the site’s remarkable stats, a topic which is surely only of interest to website owners. Throw in a few hints about college life being full of parties and sex with co-eds, and then things start to go wrong. Zuckerberg finds himself mired in arguments over copyright and invasion of privacy. Again, how much interest can this be to Joe Public? Then the trailer ends on a horribly flat emo-rock like bit of philosophy, which actually made the audience groan when I saw the trailer at the cinema recently. Another thought is that the title, The Social Network, is bad and just sounds dull. Why didn’t they stick with The Accidental Billionaire, the book this film is based on and which sounds witty, interesting and dramatic?

The reason the film seems so unappealing is not because the concept is unpromising. The Social Network is being promoted as a film which captures the essence of our Digital age, just as Fitzgerald portrayed the Jazz age, and all its excesses, in The Great Gatsby. Yet, surely Facebook is more a symbol of the mediocrities of the digital world than its virtues or excesses? The site may have five hundred million users, but many of the people I know who have Facebook accounts have come to hate the site, finding it addictive and vacuous. This is exactly how I came to regard it before I deleted my account, which they don’t make it easy for you to do (don’t be tricked into simply deactivating your account). Facebook has become a long running Reality television show for the internet, and like most Reality TV I suspect the wheels will come off soon enough. If The Social Network managed to capture some of these issues about the Digital age and Facebook, I think it would make for a more compelling movie.

Perhaps Fincher should stick to what he does best. I’m looking forward to seeing his Hollywood adaptation of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, although he would be hard-pressed to match the original Swedish adaptations.

Writing the Hardy Boys

Crime and detective fiction for children and young readers is a neglected sub-genre that nevertheless includes some of the best known, most popular, and most ridiculed of all crime and detective stories. In the United States the Stratemeyer syndicate dominated the market for children’s mystery stories for several decades from the 1920s. Edward Stratemeyer’s careful market research, and his skill in creating formulaic plots his writers could flesh out into stories, made him rich. What happened to the hundreds of ghost writers who worked for him, though, is less uplifting. The commoditisation of writers on the Web seems in many ways to be a new story, but writers, and writing, have always come cheap.

A piece in the Washington Post by Gene Weingarten, uncovers the life of Leslie McFarlane, a writer of Hardy Boys books for Stratemeyer, who paid him, in the 1930s, the miserable sum of $85 for 45,000 words. McFarlane, whose pseudonym was Franklin W. Dixon, was, as the article points out, one of the most widely published writers of his time, but had greater aspirations than this anonymous hack work. He struggled for years to feed his family and keep a roof over their heads, always hanging on to the idea that one day he would write something other than “juveniles.” But in the end the Hardy Boys consumed him. From the article:

One day he answered an ad from the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a fabulously successful enterprise that wrote children’s books through a conveyor-belt production process. The New York syndicate made the strangest offer: Would McFarlane like to write books for youths based on plot outlines Stratemeyer would supply? He would be paid by the book, and have no copyright to the material. In fact, he could never reveal his authorship, under penalty of returning his payments. The company shipped him samples of some books about a character named Dave Fearless — dreadful, thickheaded novels with implausible plots and preposterous narrative.

…

McFarlane finally unchained himself from the Hardy Boys in 1946; the syndicate didn’t care. It found another hungry writer to continue the series. To date, there are more than 100 Hardy Boys mysteries, and they are still going strong. In 1959, many of the old Hardy Boy books were redone, streamlined, modernized, sterilized. McFarlane was never consulted, but he didn’t mind. Nor did he feel ripped off by their fantastic success. A deal is a deal, he always said. He agreed to it, so he couldn’t complain.

British Gangsters and their Curious Contribution to Literature

Just last month the Daily Mirror ran the story that convicted criminal Ronnie Biggs, who for years evaded justice for his role in the notorious Great Train Robbery, was to be given a lifetime achievement award for his contribution to crime, yes crime!, at a £50-a ticket gala dinner at a venue in Slough. The event, which was publicised as ‘To Rio and Back’, took place on August 29th. But, on the website of self-proclaimed gangster and celebrity author Dave Courtney there is a post dated August 27th in which Courtney rants about how the Home Office had decreed that if Biggs attended the event, alongside an assortment of well-known gangsters and ex-convicts, he would have his license revoked and be returned to prison immediately. I can find no reviews of ‘To Rio and Back’ on the internet, so I assume it went ahead without Biggs’ presence.

I support the release of prisoners on compassionate grounds, including Biggs who was released from prison over a year ago after being informed that he had only weeks to live, but it stands to reason that this policy is to allow them to spend the very end of their life with their family, and not to be applauded on stage by a rabble of fellow gangsters talking about how ‘ard they are. Over the last decade there has been a proliferation of grossly offensive gangster memoirs clogging up the shelves in the True Crime section of bookshops. Courtney himself has authored such literary classics as Stop the Ride I Want to Get Off (1999), Raving Lunacy (2000), Dodgy Dave’s Little Black Book (2001), The Ride’s Back On (2003), F**k the Ride (2005) and Heroes and Villains (2006). There is a silver lining to this dark literary cloud; Britain has never experienced gangsters as wealthy and powerful as those seen in Italy and the United States. American Gangsters like Al Capone, Sam Giancana and John Gotti never had the time to write books or organise gala dinners, although to be fair all these examples met their demise due to their love of the limelight. As we live in a country relatively unplagued by organised crime, perhaps we should be grateful that the worst we have to endure is the literary equivalent of celebrity gangsters parading their life around like your average exhibitionist Big Brother contestant.

The Secret In Their Eyes: Campanella, Borges, Bolano

I was predisposed to suspicion about Juan José Campanella‘s crime drama The Secret In Their Eyes (El Secreto De Sus Ojos) as it had beaten two absolutely stunning films – Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon and Jacques Audiard‘s A Prophet – to the best foreign film Oscar earlier this year. I had suspected the traditional conservatism of the academy to have won out – a conservatism that saw Guillermo Del Toro’s bold political fantasy Pan’s Labyrinth lose to the rather stolid drama The Lives Of Others in 2007. However, my interest was piqued about Campanella‘s film for a number of reasons – the critical comparisons to Borges, the fact that I had never seen any cinema from Argentina before, and the (admittedly more tenuous) proximity of the film’s release to the English translation of Roberto Bolaño’s Central and South American masterpiece 2666, which (amongst many, many other things) played upon the conceits of the whodunnit and police procedural with a decidedly Borgesian narrative strategy. Borges is, of course, Argentina’s 20th century literary godhead, and the idea that this Buenos Aires crime drama could have absorbed some of the narrative genius of that city’s great writer was too exciting to resist.

The relatively sedate, two-shot approach to the film’s first half-hour lulled me into thinking that perhaps the academy had indeed plumped for relatively safe territory, and that I might be in for a repeat of the tiresome experience I had watching the cinematic adaptation of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo earlier in the year. However, to my delight this initial approach merely lays the groundwork for a subsequent narrative fragmentation that both beguiles and devastates. Campanella bides his time carefully, building character’s histories and circumstances delicately and indirectly, before employing an ever increasing set of technical and formal flourishes which, rather than providing style for their own sake, actually mirror the insecurity and unsteadiness that underpins the central murder case. The tipping point – around halfway through the film – is a dazzling continuous five-minute take involving a police pursuit around a football stadium that begins with a helicopter shot hundreds of metres above the arena. From this point onward, the preceding solidity of the film’s narrative – the shot technique, the camera movement, the framing – begins to loosen and fragment, analogous to personal loyalties and hidden betrayals spiralling outward and muddying already murky waters. Campanella also sets up a series of mirroring counter-plots within the main narrative, principle among which is a genuinely affecting unrequited love story that visually and thematically touches against the central murder plot on a number of occasions without feeling the need to amplify or overstate the connections.

I will not spoil the film’s climax – during which the narrative fragmentation reaches hitherto unprecedented levels – but I will state that Campanella manages to deliver a quietly devastating ending that resists the kind of cheap clean-up and closure favoured by many detective dramas while still remaining narratively satisfying. I wish that the film had ended about three minutes before it actually did – if you see the film or have seen it you may know what I mean – but this cannot damage the excellent and emotionally satisfying climax already laid down.

So, is it like Borges? Well…no. The comparisons turn out to be erroneous – any film that could claim to be strongly influenced by Borges would have to lean more strongly toward avant-garde narrative technique – David Lynch’s Inland Empire (with its circular record-groove narrative motif) is a good recent example. The Secret In Their Eyes is ultimately too technically ‘straight’ to narratively resemble the finest works of Borges. This is not Campanella‘s fault of course – as far as I am aware he made no such narrative claims for the film personally. Is it like Bolaño? It is certainly closer to the spirit of his writing than to Borges, particularly in its focus upon the emotional correlation between the lives of policeman and killer, as well as the spectre of political corruption that lies over both this film and 2666. The baffling decision to give the film a mid-August release date, when it would have found a very appreciative home in October or November (and the inevitable and depressing shortage of UK prints) has meant that despite critical acclaim the film has failed to make the optimum impact. As it still lingers around cinemas nationwide, there remains time to appreciate this film before its diminishment on the small screen.

Ray and Cissy Chandler to be Reunited

I’ve written before about the campaign to have the ashes of Cissy Chandler, wife of Raymond Chandler, moved from the storage facility where they have been since her death in 1954, and placed next to those of her husband. This morning, Loren Latker, who has been leading the campaign, wrote to say that on Wednesday a San Diego court granted the petition to have the ashes moved. Naturally, he plans to celebrate with Gimlets at the grave.

Loren, his wife Dr. Annie Thiel, lawyer Aissa Wayne, and many others, have put a lot of effort into getting this result and I’d like to thank them and everyone who signed the petition that was at the top of this blog over the summer. Sign On San Diego has more:

An unfinished chapter in the life of Raymond Chandler has all the drama,Hollywood links and detective work of one of the author’s suspense novels.

It began 56 years ago when the cremains of his beloved wife, Pearl Eugenia “Cissy” Chandler, wound up on a storage shelf at San Diego’s Cypress View Mausoleum.

The celebrated detective novelist, who was despondent after her death and died 4½ years later in La Jolla, is buried a mile away at the city-run Mt. Hope cemetery.

Update: I was interviewed a few weeks ago by John Rogers of the Associated Press about Chandler, his wife, and Loren Latker’s efforts to reunite them. The article has shown up in The Guardian, among other places.

The Flaws in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy

Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy was a part of my Summer reading, and it was a very enjoyable experience to spend hours of my time completely hooked on the dark and riveting tales of computer hacker Lisbeth Salander and crusading journalist Mikael Blomkvist. So much has been written about the Millennium trilogy that I doubt I could add much to the praise, but what struck me in particular was Larsson’s brilliant handling of many varied plots and crime sub-genres. The narrative seamlessly moves between and merges elements of the locked room mystery, whodunnit, corporate intrigue, political conspiracy thriller and historical fiction.

However, as Chris has argued on these pages, the concluding volume of the trilogy, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, is certainly the weakest of the series. I suspect the editing process had not been completed at the time of Larsson’s death as the novel seems far too long and needs refining. Without meaning to sound killjoy or to give away any spoilers, here are a few other areas where I felt the third novel was disappointing:

There is a long sub-plot involving Blomkvist’s occasional lover Erika Berger leaving Millennium magazine to become editor of a powerful national newspaper. While this is an entertaining and suspenseful diversion it seems to go on forever and the payoff is underwhelming.

I never found the character of Ronald Niedermann to be plausible. Niedermann is a psychopathic giant who is incapable of feeling pain, and whenever he is around the story descends into hokum.

About two hundred pages before the end of the third novel it becomes fairly obvious that the bad guys are screwed and the good guys become annoyingly self-righteous and verbose. The climactic courtroom trial seems to lose all suspense as a consequence.

Again, these are minor quibbles which, on the whole, don’t take away from Larsson’s brilliance as a writer and the Millennium trilogy’s reputation as a stunning achievement in crime fiction. There is an element of tragedy in reading the novels as we know Larsson never lived to see their remarkable success. I was left hungry for more and would love to see a fourth novel if the manuscript ever emerges, and if Larsson’s partner Eva Gabrielsson is ever awarded the fair settlement that she deserves. Although I would hope a fourth novel, despite Larsson’s passing, would receive a more vigorous editing and even redrafting process than The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest.